-

INTRODUZIONE AL PANTHEON PLATONICO

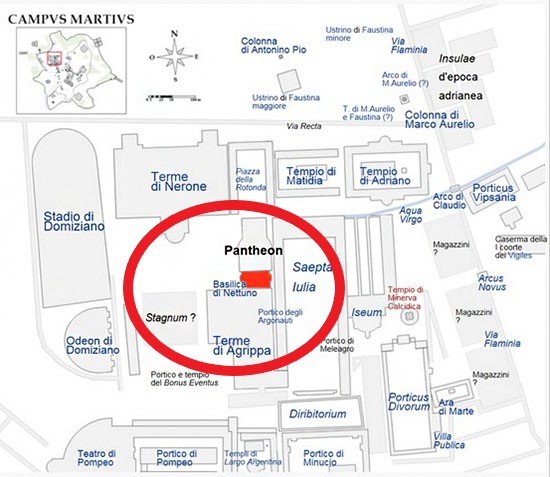

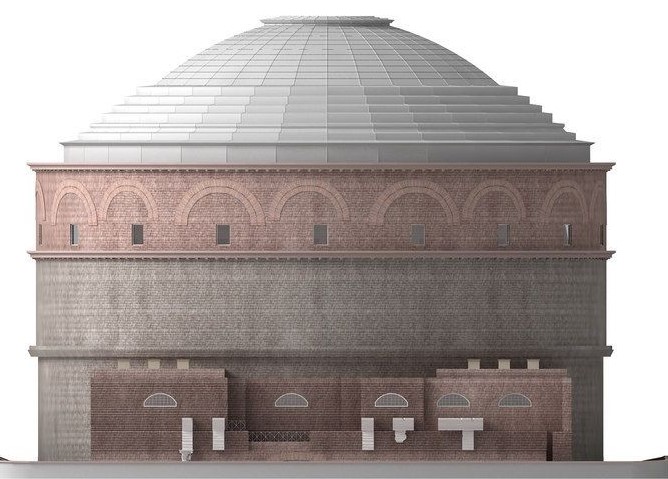

Il Pantheon è uno dei principali e più famosi monumenti antichi al mondo. Ogni anno milioni di persone fanno file, sempre più lunghe, per potere entrare velocemente a vedere il tempio circolare.

Nel frontone reca ancora l’attribuzione di esso al suo costruttore Marco Vipsanio Agrippa, amico dell’imperatore Ottaviano Augusto: da secoli è stato studiato, ma ancora nessuno è stato in grado di comprendere a che cosa servisse e perché esso avesse questa strana forma circolare. Né è stato compreso il senso della cupola con il suo buco al centro.

In questo articolo tenteremo di dare una spiegazione.

Per fare ciò ci leveremo gli occhiali moderni e tenteremo di vedere il mondo per come lo vedevano gli antichi.

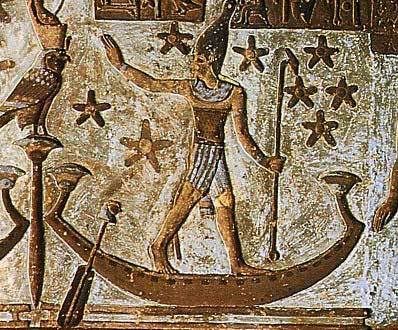

Per prima cosa vediamo all’interno del tempio un simbolo stellare.

Di rassomiglianza al cielo parlavano fonti coeve come Dione Cassio e Ammiano Marcellino.

Ipotizziamo, dunque, che esso possa essere servito a finalità legate in qualche modo agli astri.

D’altronde, per come noto, l’imperatore Ottaviano venne ufficialmente dichiarato asceso agli astri con deliberazione del Senato del 17 settembre dell’anno 767 Ab Urbe Còndita (14 Dopo cristo).

Qui la foto di una moneta augustea che ritrae la costellazione del Capricorno, quale simbolo dell’aurea aetas di Saturno, dicono gli studiosi. Secondo noi rappresentava invece la porta degli dei per l’ascesa stellare, sita nel segno del capricorno e narrata da Omèro nell’Odissea, prima, e poi da Porfirio nel “Antro delle Ninfe”. Altrettanto la gemma augustea, qui raffigurata, porta accanto all’imperatore il segno del Capricorno.

L’ascesa dell’imperatore era, dunque, solo propaganda politica? Lo scopriremo tra poco. Cominciamo con chiederci che cos’era il Mondo per gli antichi?

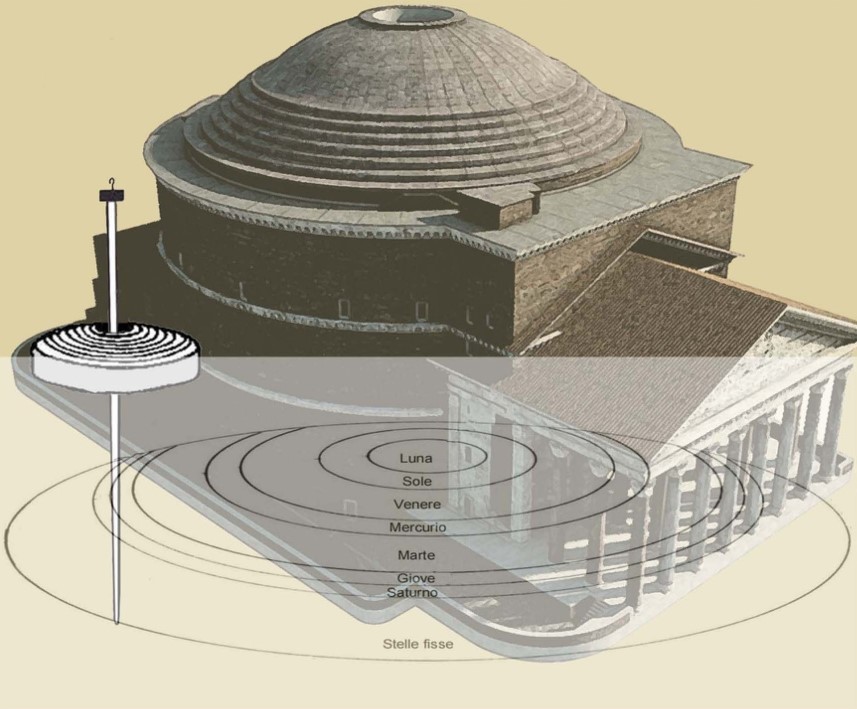

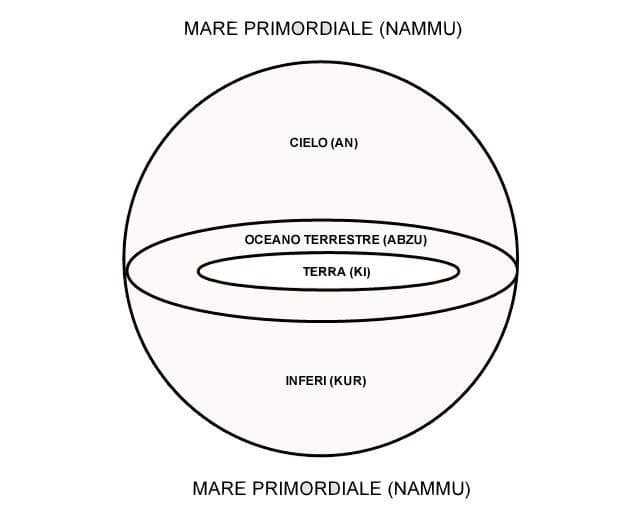

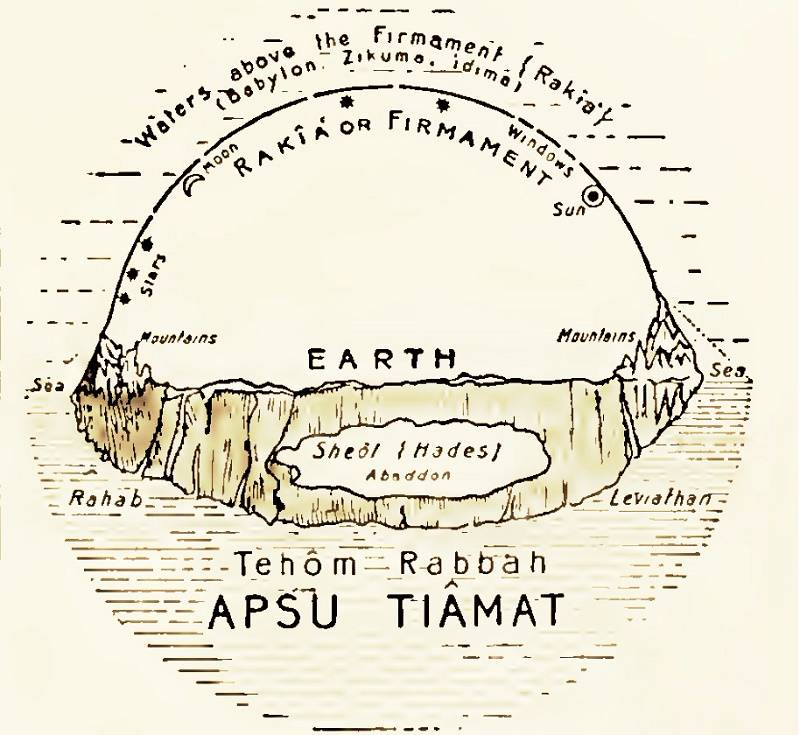

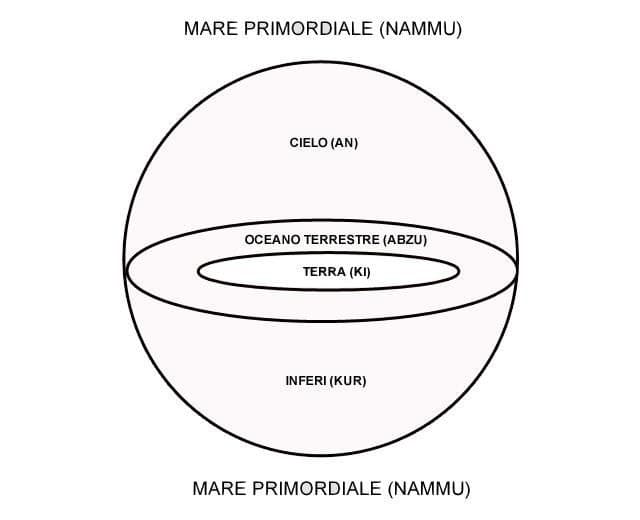

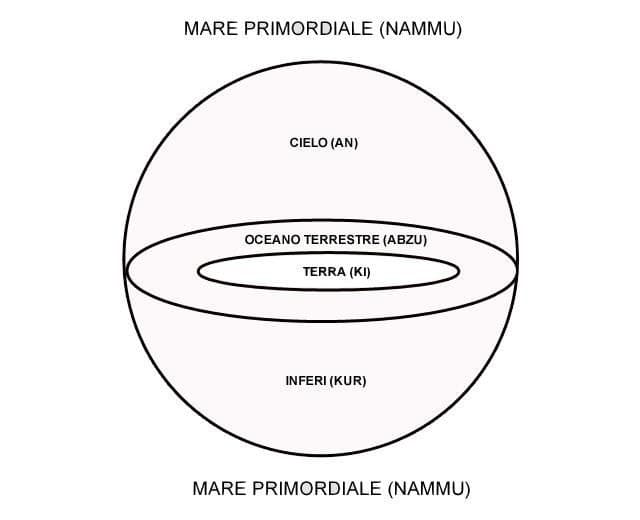

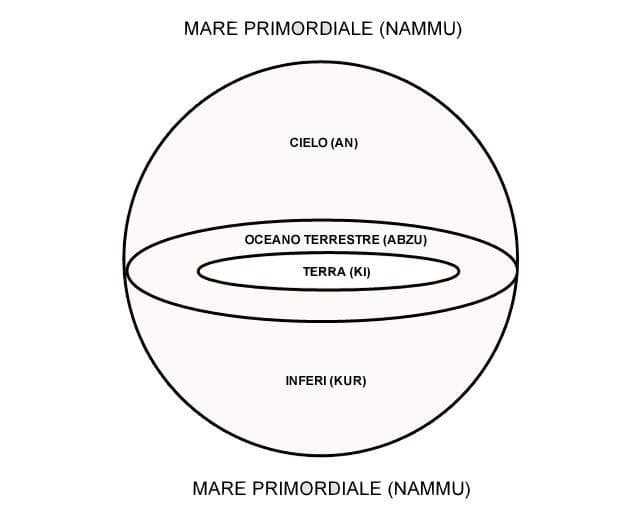

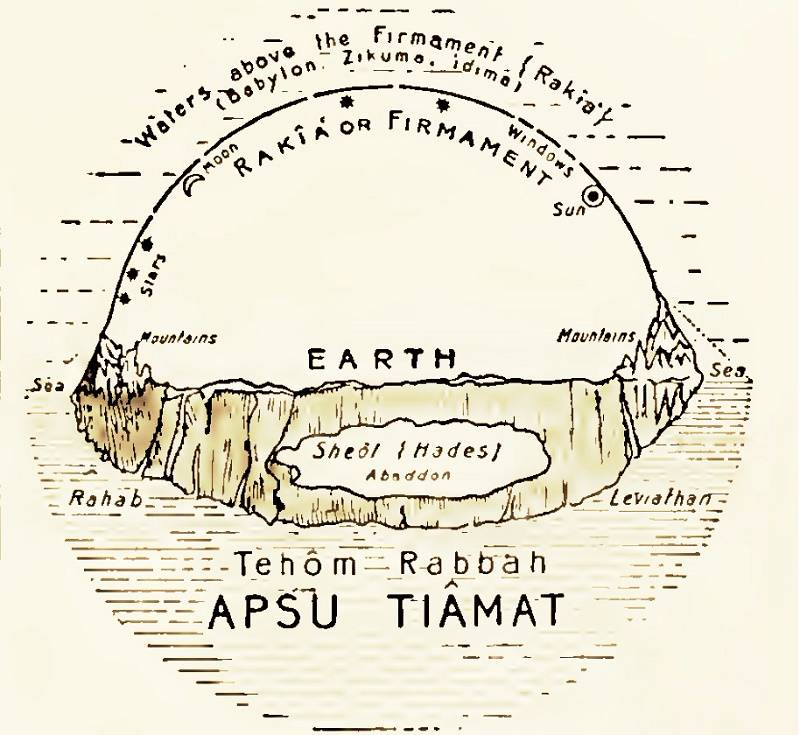

Qua vediamo la visione antica dei sumeri. Il mondo era per loro costituito da una sfera, composta dalla cupola del cielo (di an) , dalla terra (di ki) e dall’oceano terrestre (di abzu) al centro lungo l’equatore della sfera. Sotto gli inferi (di kur). La sfera era a sua volta circondata dal mare primordiale (di Nammu).

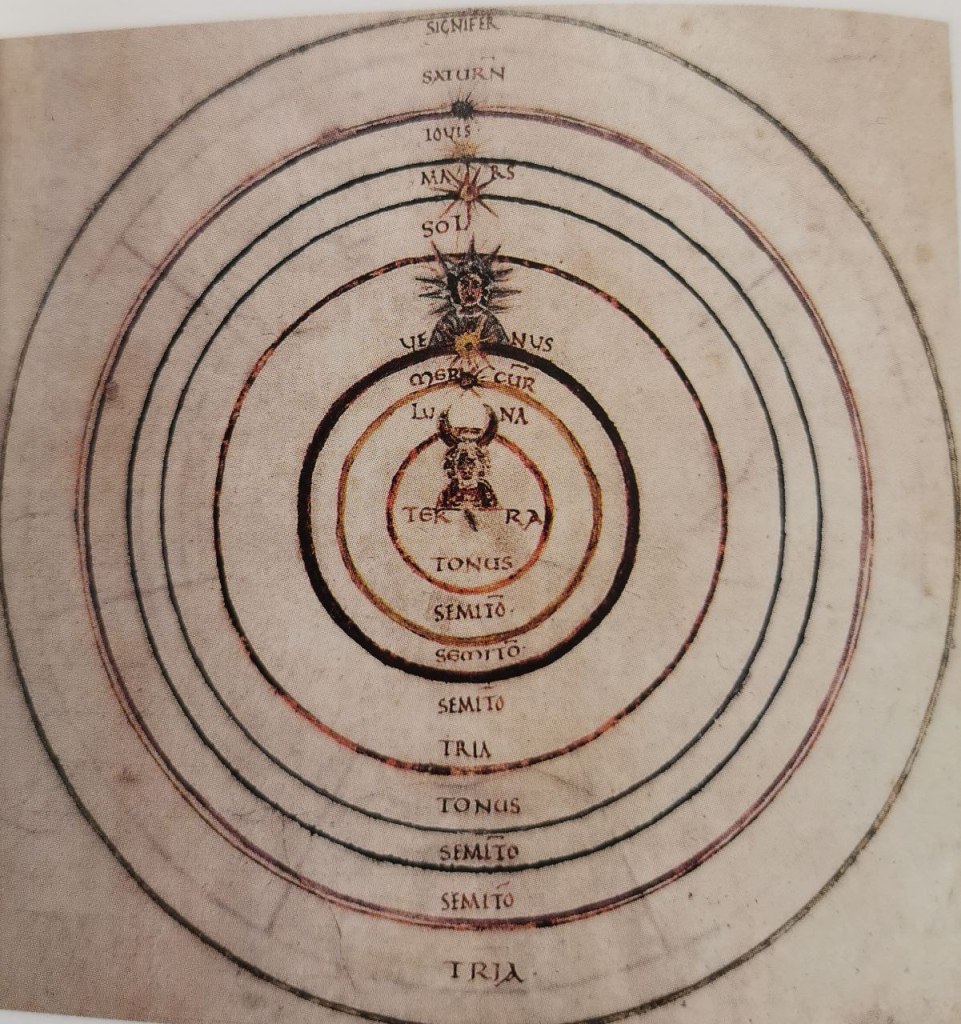

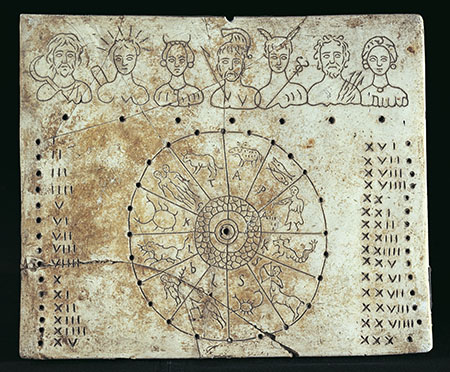

Il firmanento che circondava la sfera era adornato lungo tutta la sua circonferenza da costellazioni, per come visibile nel mappamondo di epoca Romana custodito a Mainz in Germania).

Anche la famosa statua di Atlante che sorregge la sfera del mondo mostra che sulla circonferenza di essa sono visibili le costellazioni.

Similmente, nel dipinto di Annibale Carracci, Atlante sostiene il mondo con le costellazioni ritratte sopra di esso, nel firmamento.

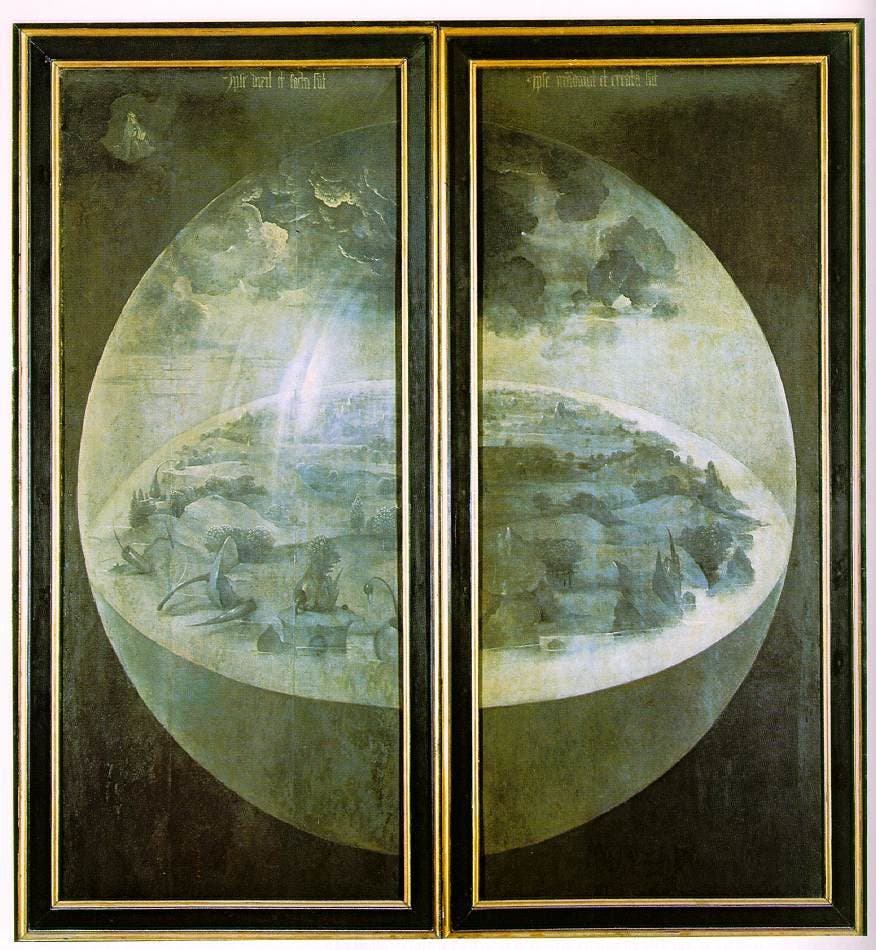

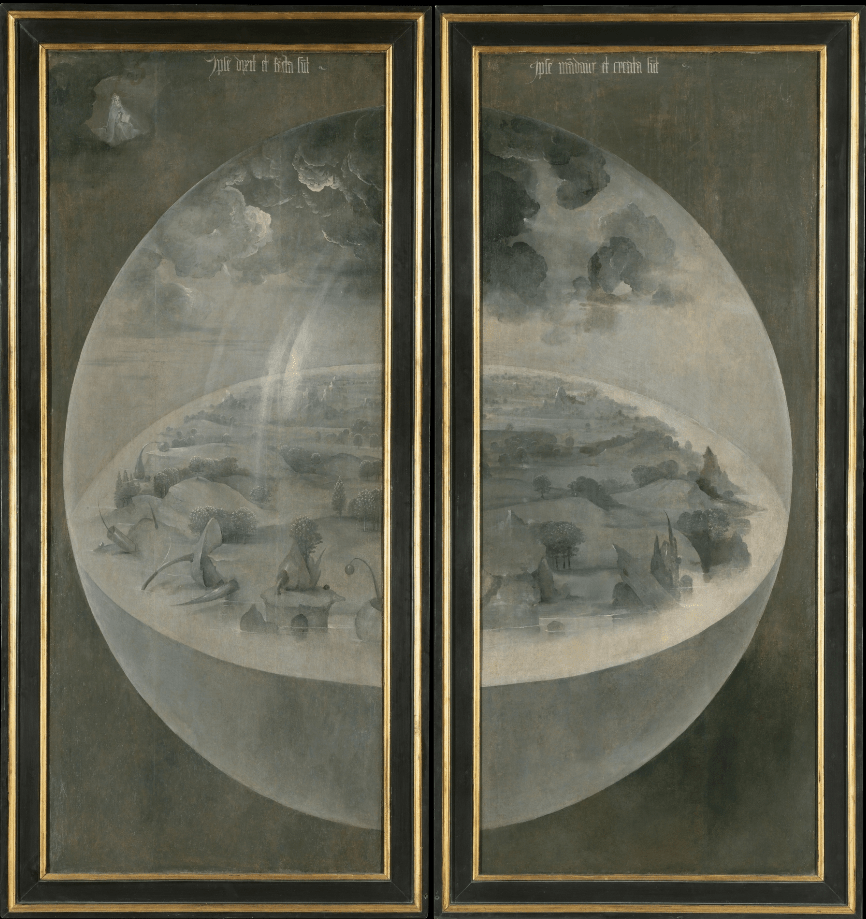

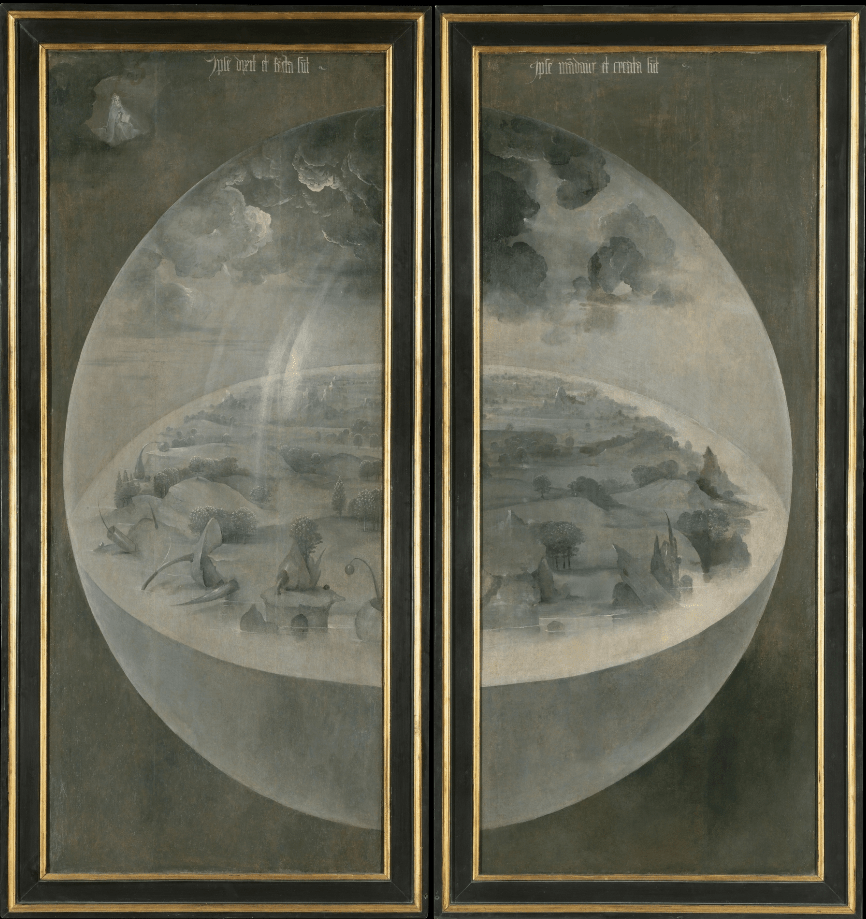

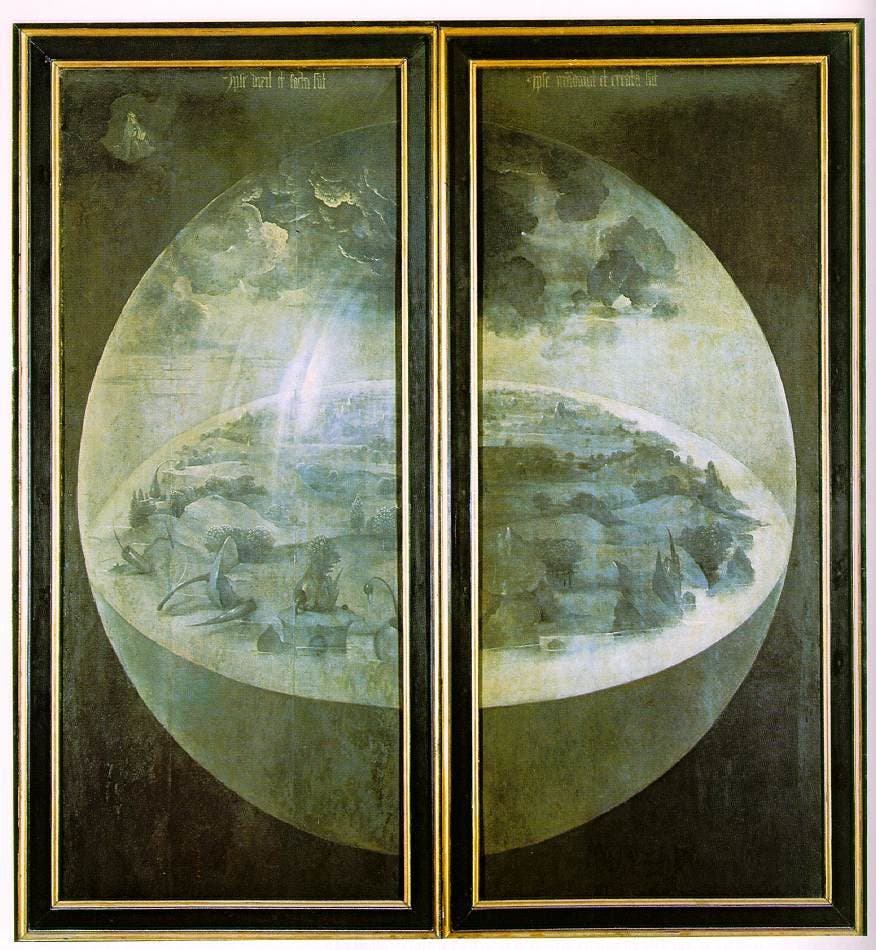

Notiamo, dunque, una differenza fondamentale: la terra non seguiva la circonferenza della sfera diventando sferica a sua volta, ma era stazionaria piana sull’equatore della sfera. il dipinto “Il giardino delle delizie terrestri” di Bosch, aiuta a capire meglio il concetto.

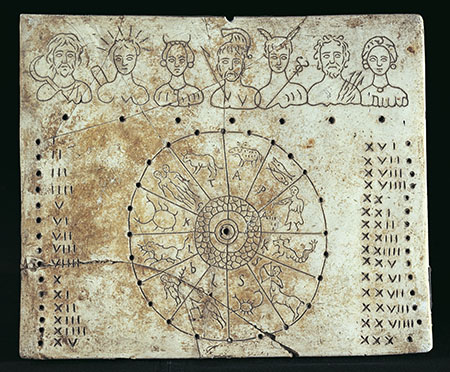

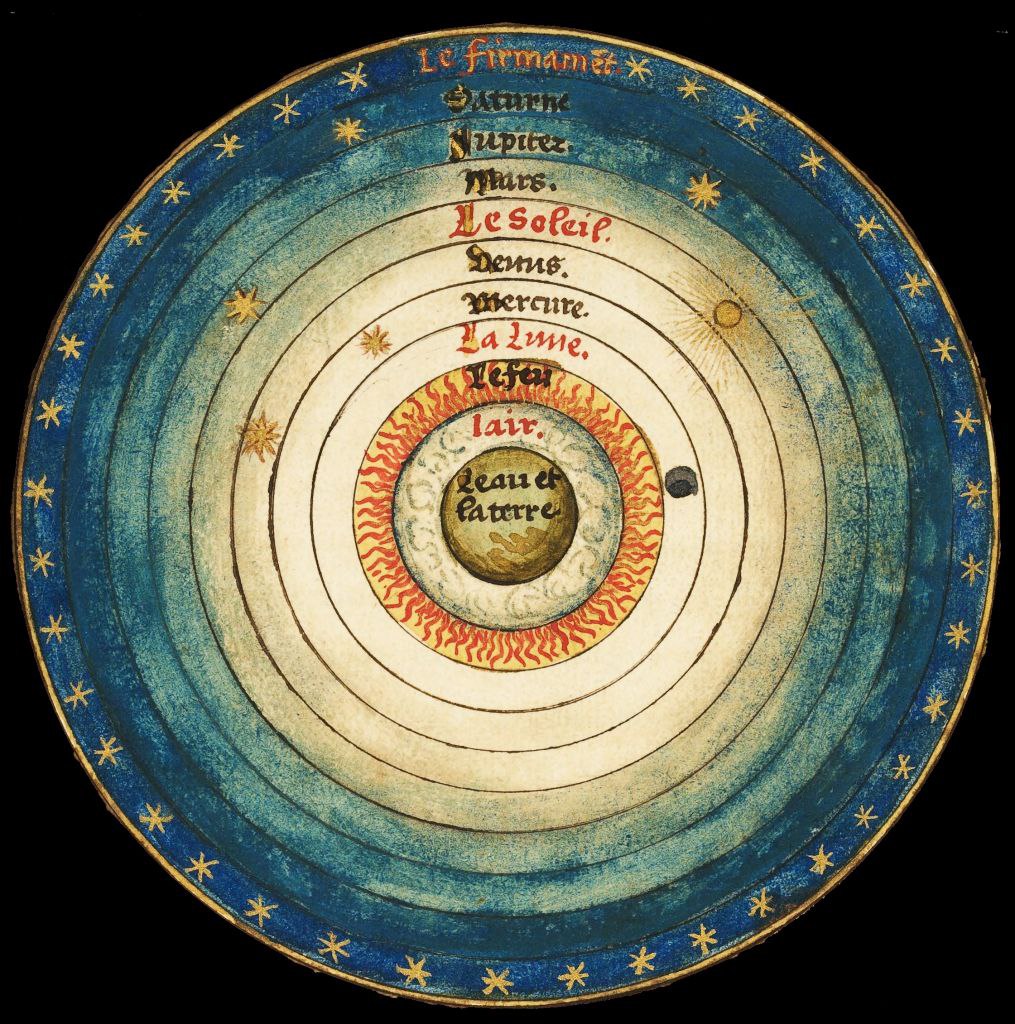

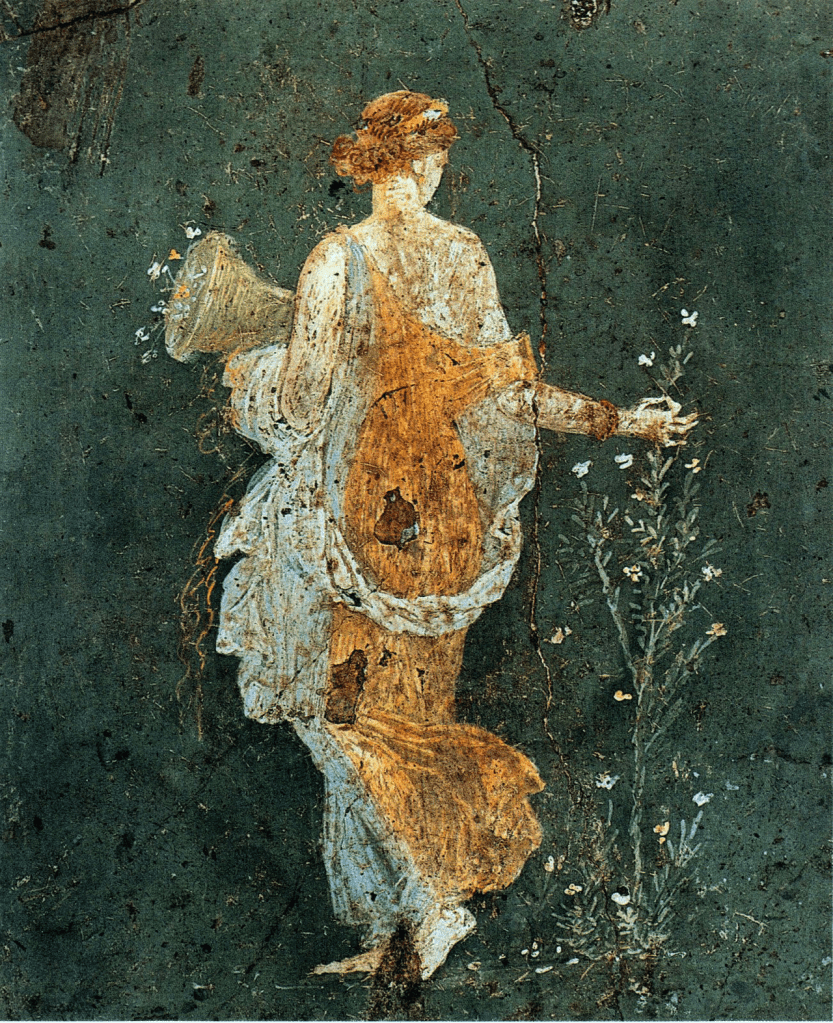

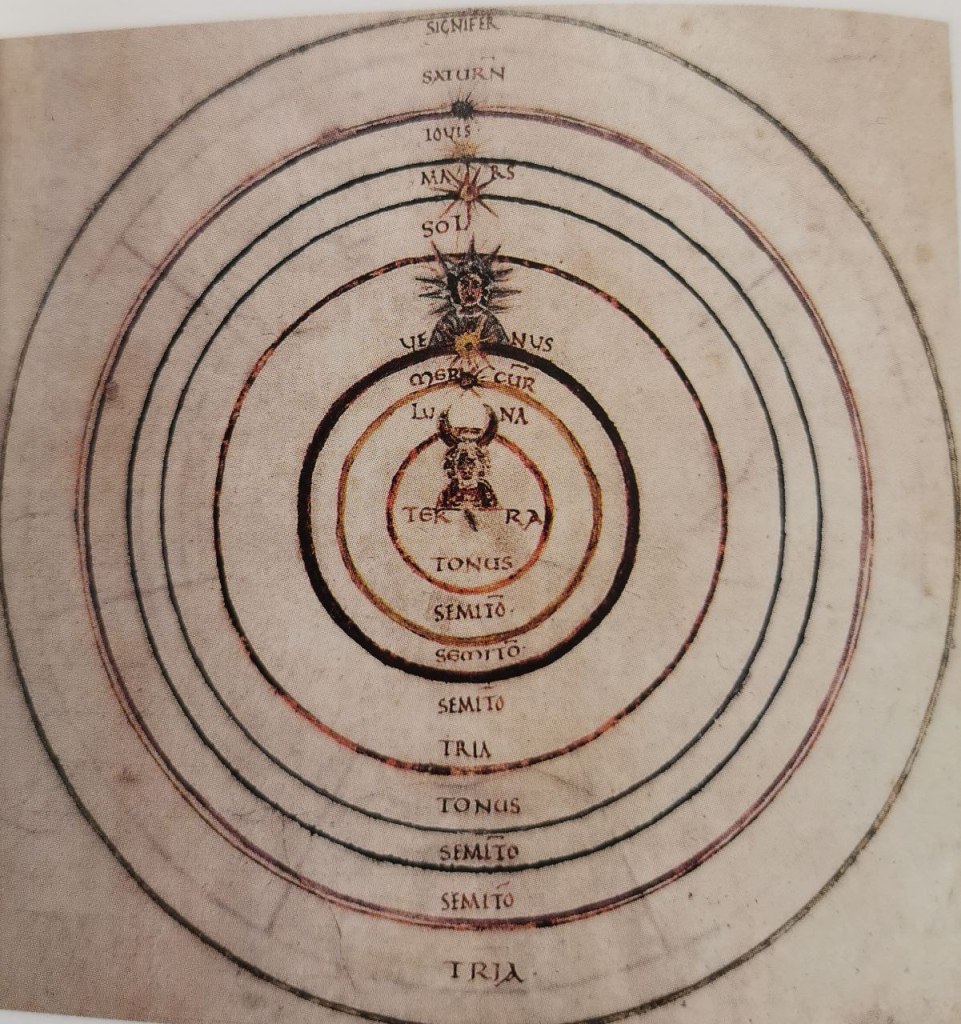

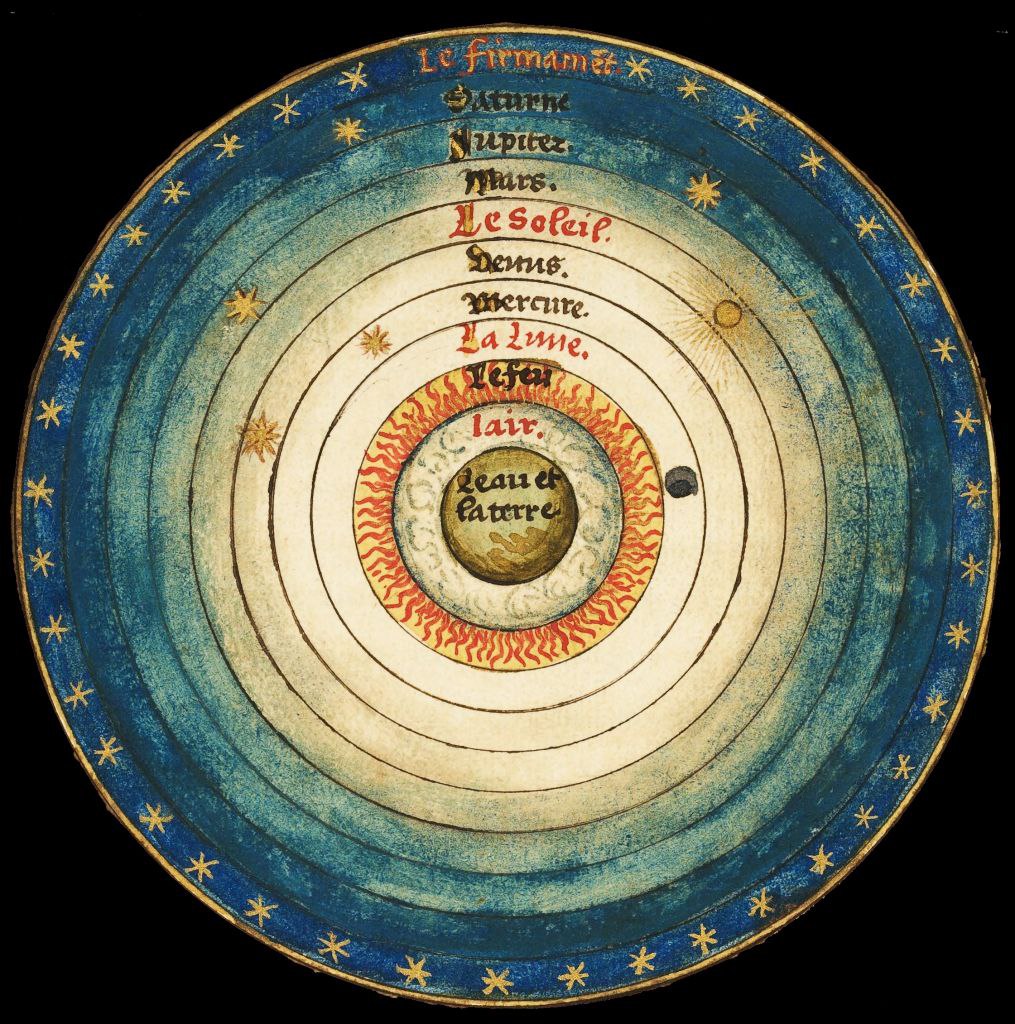

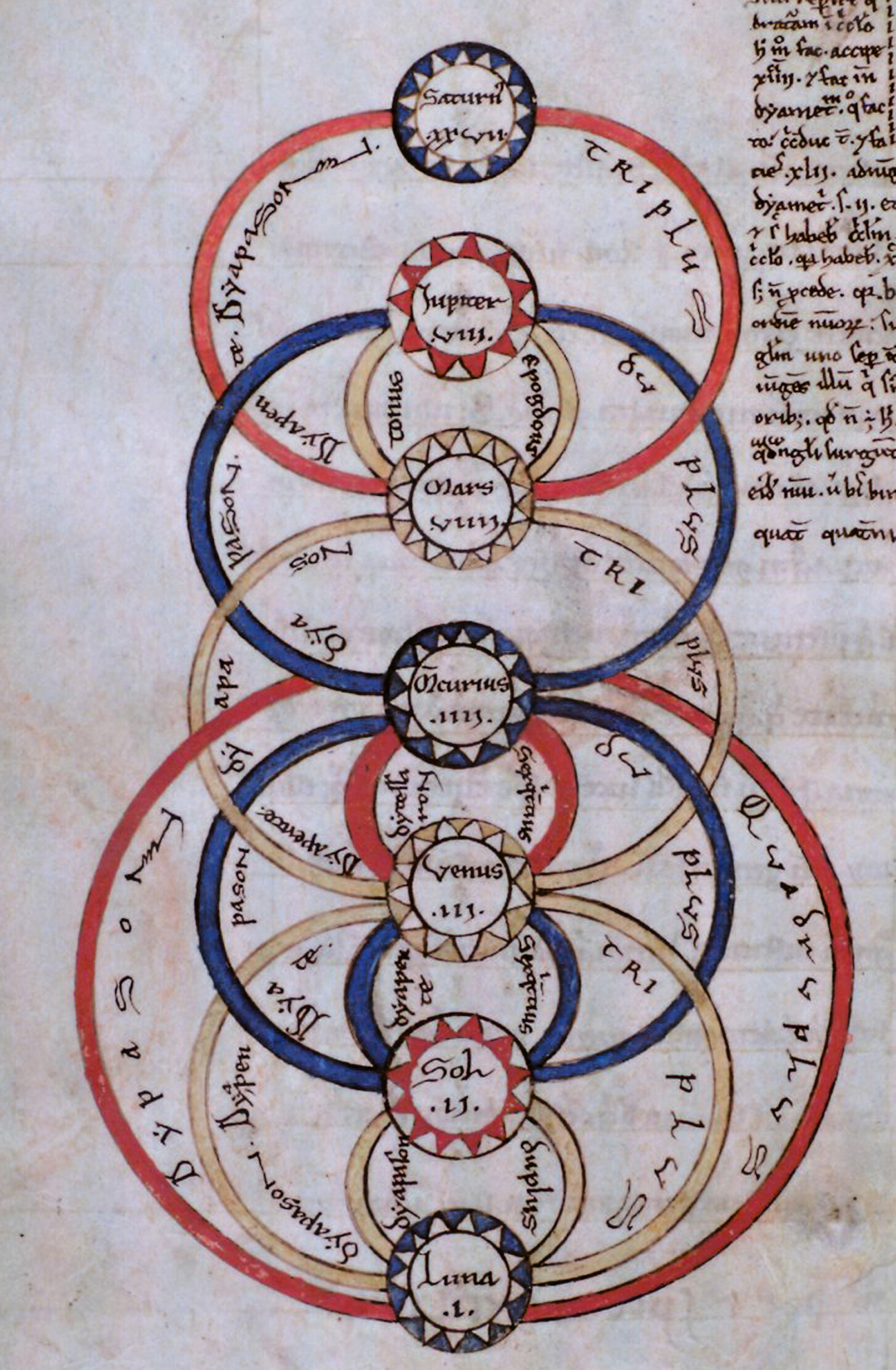

Il cielo, costituito da una cupola emisferica sopra e da una sotto era ripartito in 12 costellazioni che giravano attorno alla terra insieme ai sette astri, ovvero Saturno, Giove, Marte, Mercurio, Venere, Sole e Luna per come visibile in questo calendario astrologico lunare romano o in questo mosaico romano dello zodiaco.

Dicevamo che nella concezione sumera la sfera era a sua volta circondata dal mare primordiale chiamato Nammu. Vediamo le acque dell’oceano sopra il firmamento e le nuvole nella raffigurazione uno sketch di Cosmas un modello dell’universo.

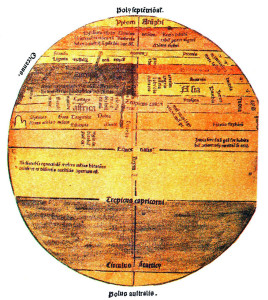

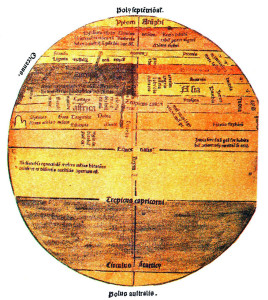

La terra stava piana all’equatore del mondo, dicevamo, per come visibile in questa mappa araba della Terra realizzata dal geografo Idrisi nel secolo undicesimo.

Essa era ripartita in varie suddivisioni climatiche per come visibile nel “Ymago mundi et tractatus alii” di Pierre d’Ailly e poi nella mappa di Sacrobosco.

Per capire meglio la differenza tra mondo e terra e la divisione tra le aree del cielo sarà utile fare riferimento alla vasta iconografia cristiana medievale prima della cosiddetta rivoluzione copernicana, che in massima parte ha creato quegli occhiali che ci impediscono di capire il mondo antico.

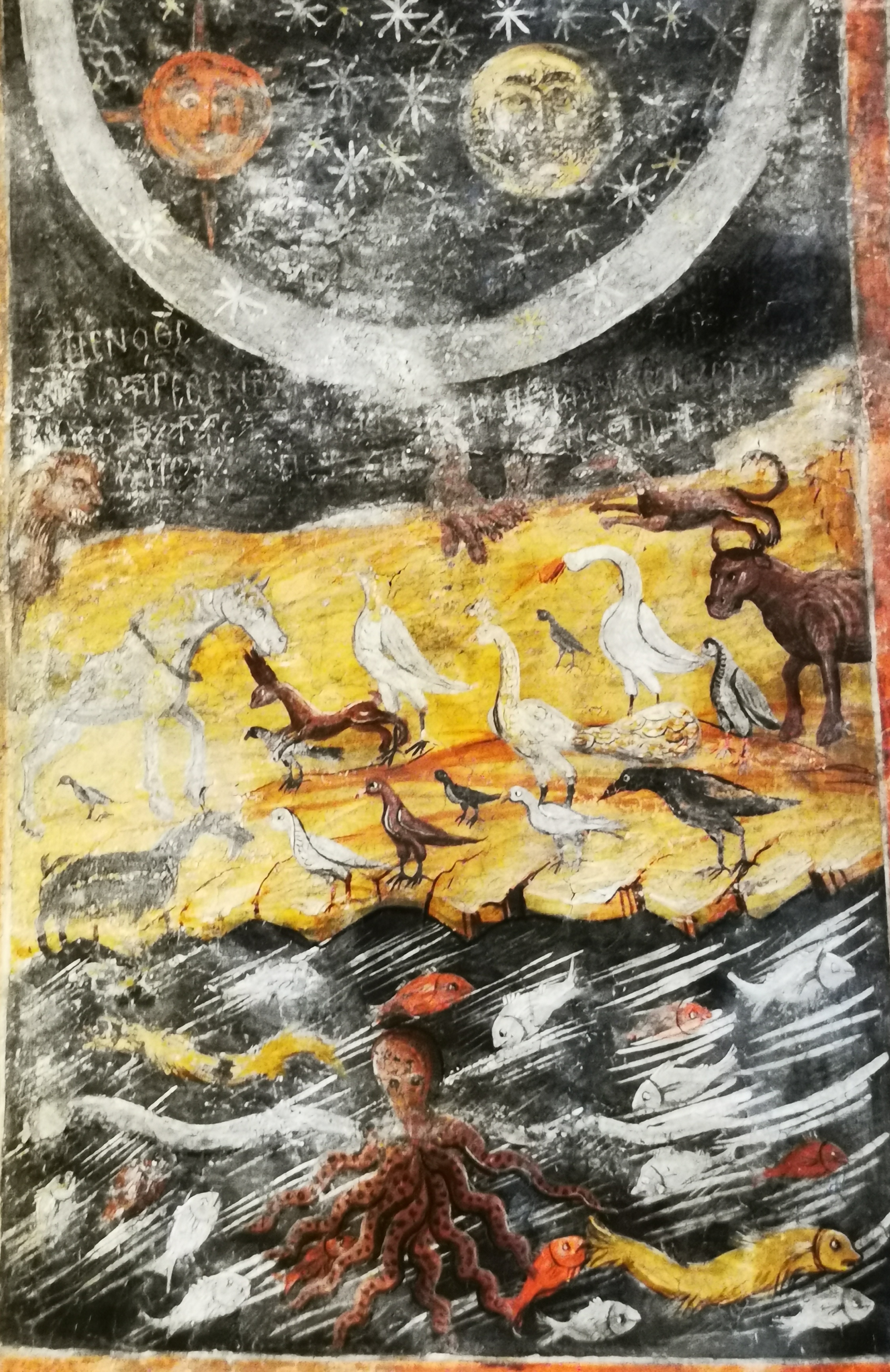

Nella Chiesa della dormizione della Theotokos di Askilipio, Rodi, Grecia troviamo degli affreschi murari del nono secolo che ci possono bene condurre:

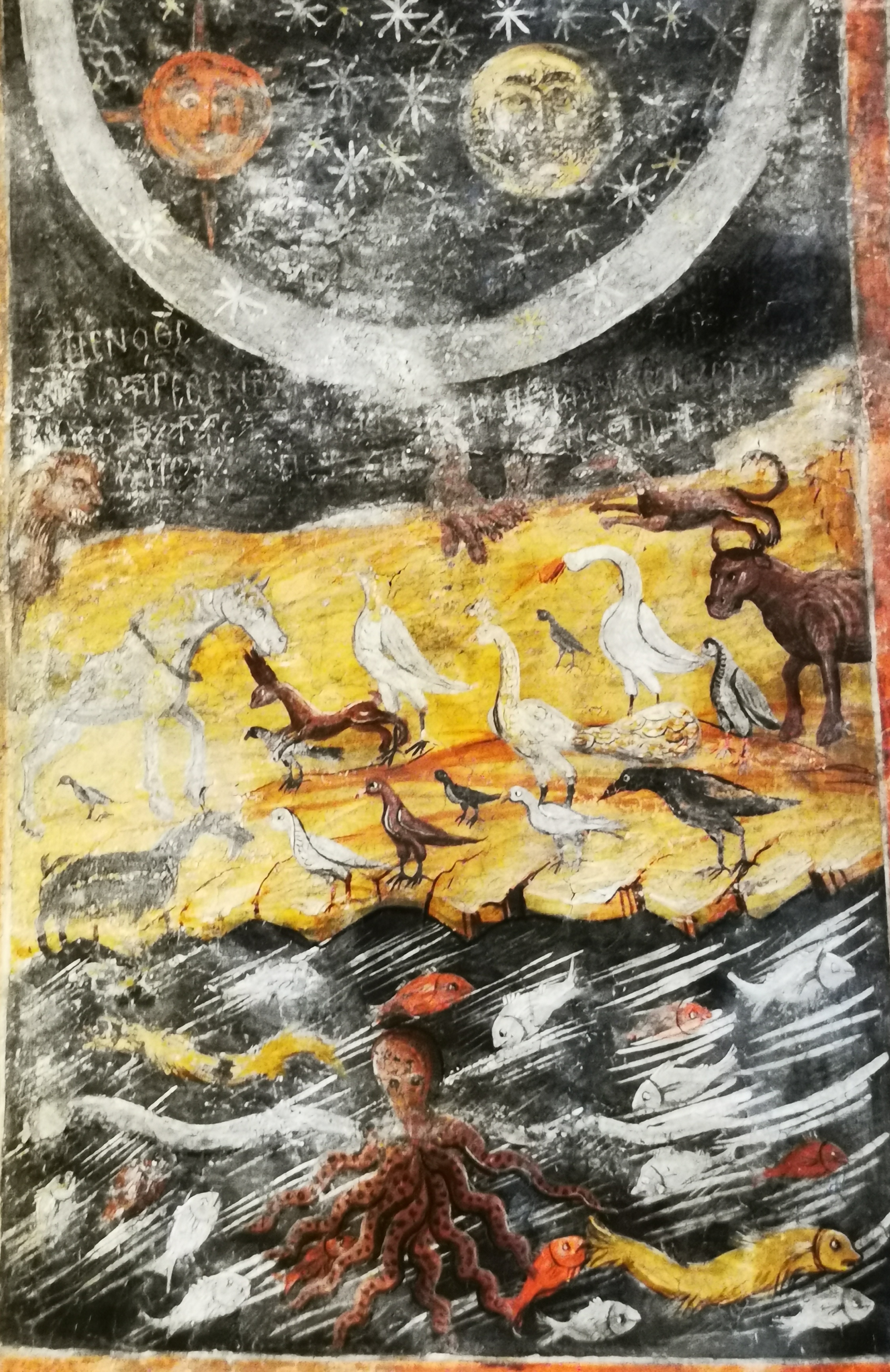

Il primo riguarda la creazione del mondo con i sette cieli da parte del Cristo, il secondo tratta della creazione della Terra, ove la creazione della Terra e’ distinta da quella del Mondo.

Infine, la creazione del Sole e della Luna e poi degli animali, dopo la creazione del Mondo e della Terra.

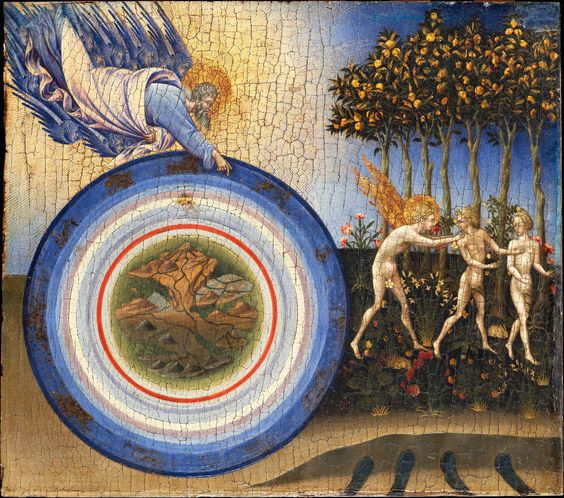

Nell’altra creazione del mondo in mosaico, del tredicesimo secolo a Venezia, basilica di San Marco, si può notare la sfera del Mondo con all’interno, Stelle, Sole e Luna.

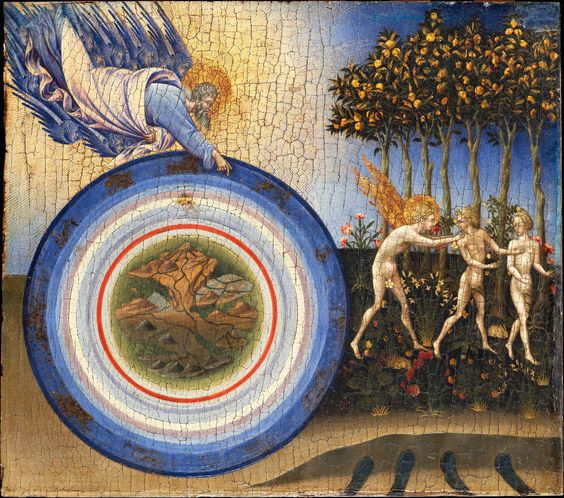

Ancora più utile il dipinto di Giovanni di Paolo, “Creazione del mondo e cacciata dal paradiso”, ove si possono vedere, attorno alla terra posta al centro, i sette cieli successivi alla sfera del fuoco e, ultima, l’ottava sfera stellata (con i simboli delle costellazioni) chiusa dal firmamento con il cerchio più scuro.

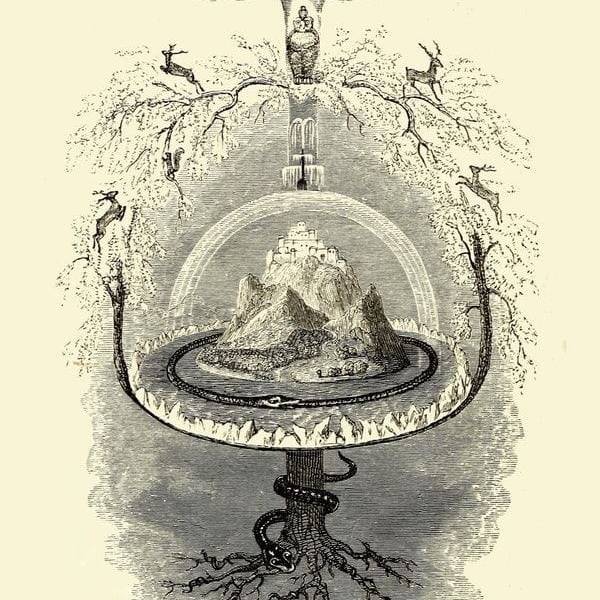

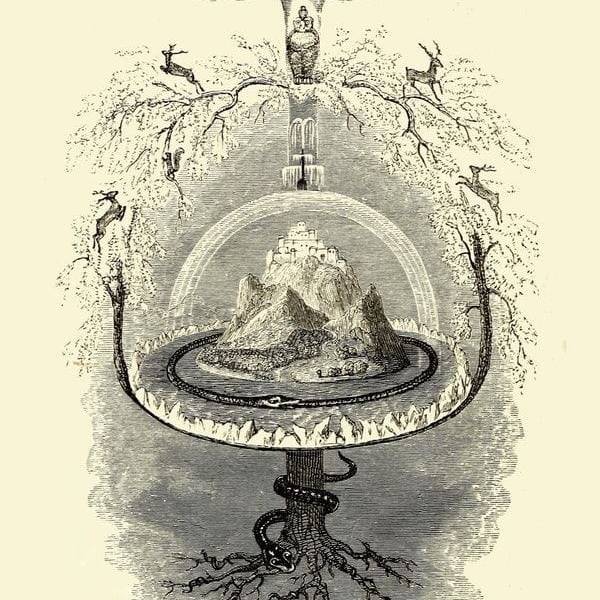

Un altro tema della grande differenza concettuale tra la concezione geografica del mondo antico e quello moderno è quello dell’axis mundi, asse del mondo, ovvero dell’asse attorno a cui girava il firmamento. Tale asse è stato denominato Yggdrasill dalle popolazioni del nord-Europa e scandinave, in particolare. Qua vediamo l’Yggdrasill in una copia di una runa in Svezia.

In un’altra riproduzione artistica dell’albero del Mondo Yggdrasill sono da notare le radici, tanto nel Cielo quanto nella Terra. L’apparato radicale stellare è denominato delle stelle beheniane, ovvero delle stelle radici dell’albero della vita, dall’arabo bahman, radice, dal momento che ciascuna di esse era considerata una fonte di energia astrologica per uno o più pianeti.

La corsa delle stelle attorno all’asse del mondo, ovvero attorno alla stella polare, qui in una foto di Ken Christison, nel mondo romano veniva paragonata alla corsa equestre.

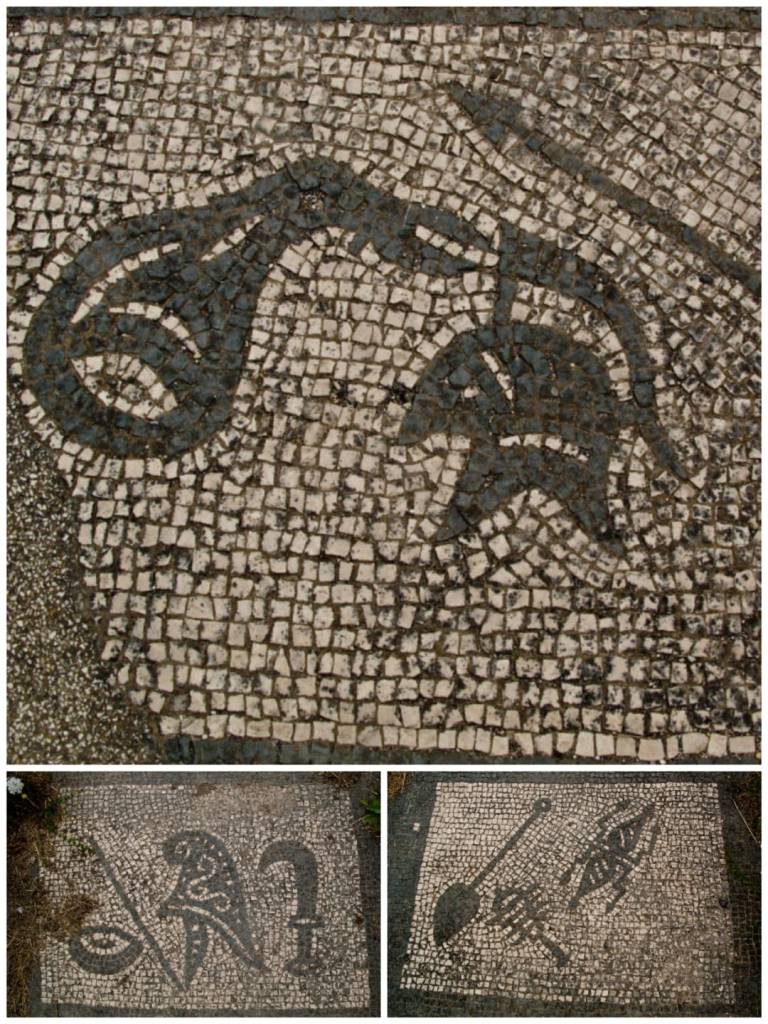

Qui vediamo nel mosaico del circo, di Villa Silin in Libia, al centro il monumento del sole, sui lati i monumenti per gli altri 6 astri.

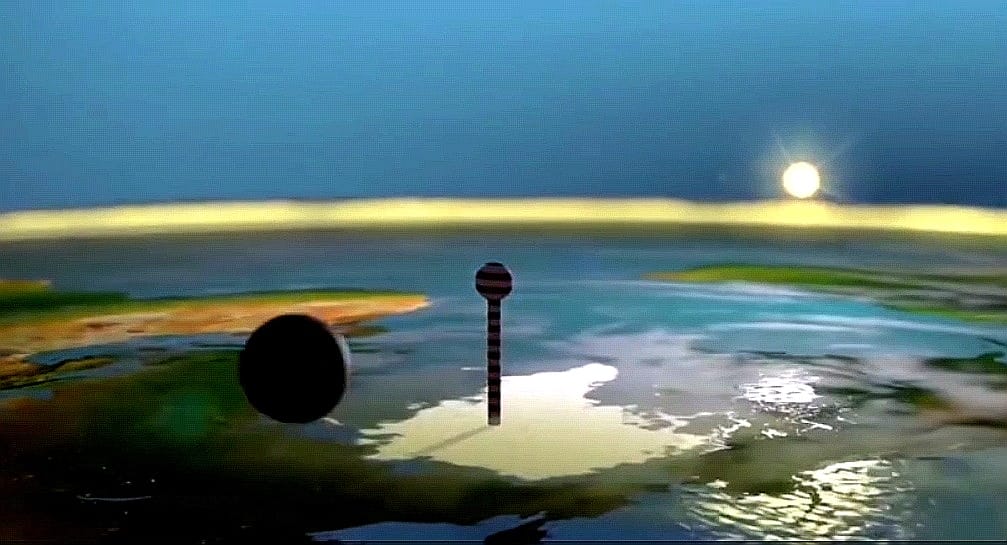

Di seguito una rappresentazione artistica della visione antica del movimento del sole e della luna attorno all’axis mundi. E ancora una rappresentazione della visione antica del movimento della cupola celeste attorno alla stella polare, posta al centro.

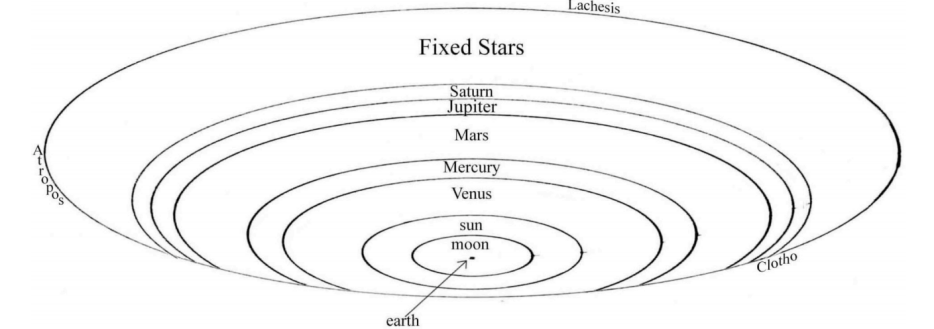

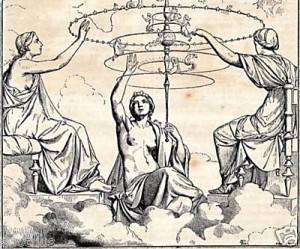

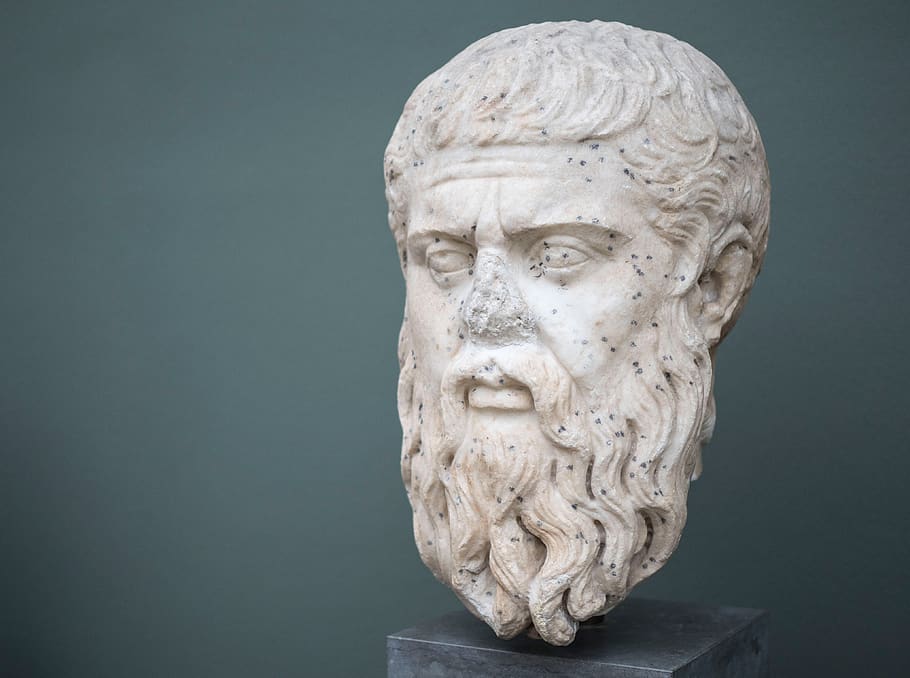

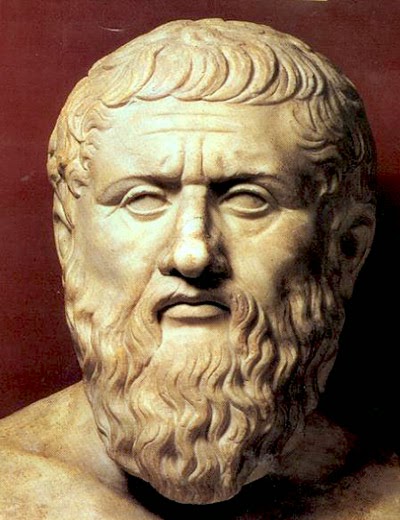

Trattiamo ancora dell’axis mundi e delle parche di cui trattava Platone nel decimo libro della Repubblica a proposito del mito di Er.

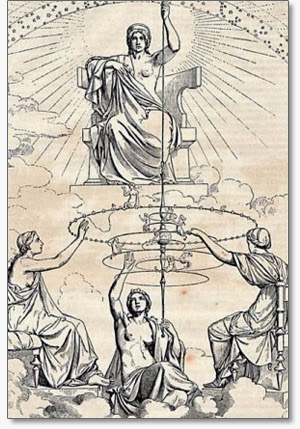

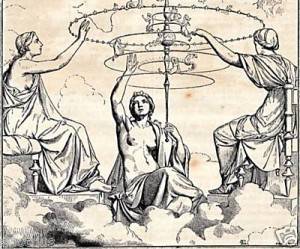

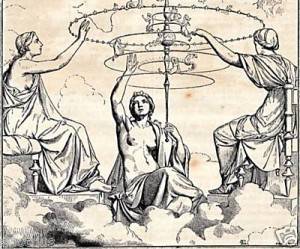

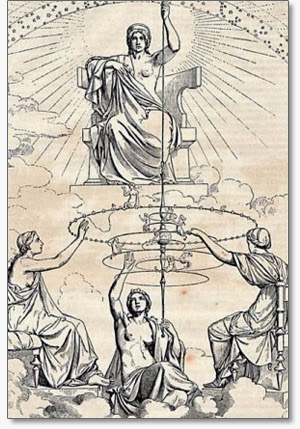

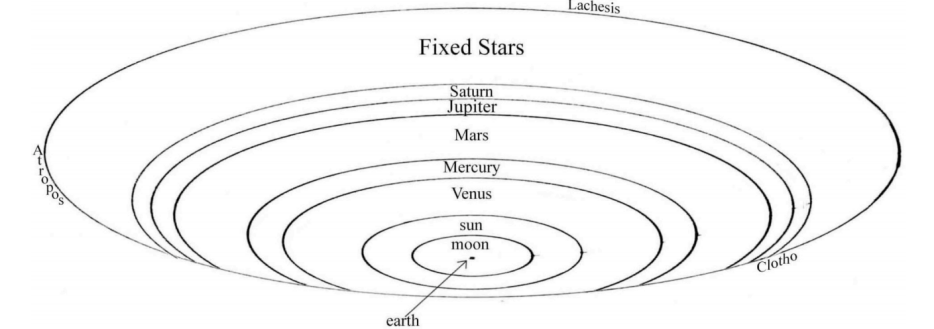

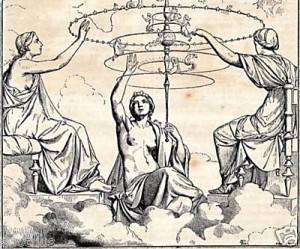

Nel disegno vediamo Ananke che regge l’asse e le parche che muovono sfere (o fusaioli come li ridefiniva Platone) attorno alla colonna di luce.

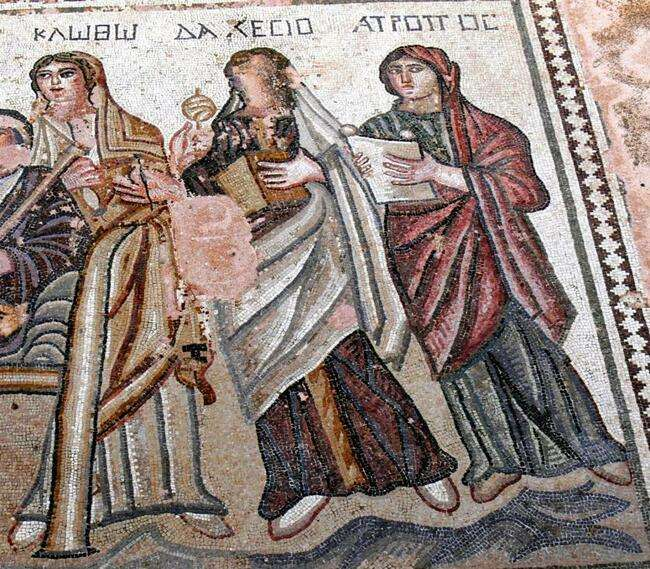

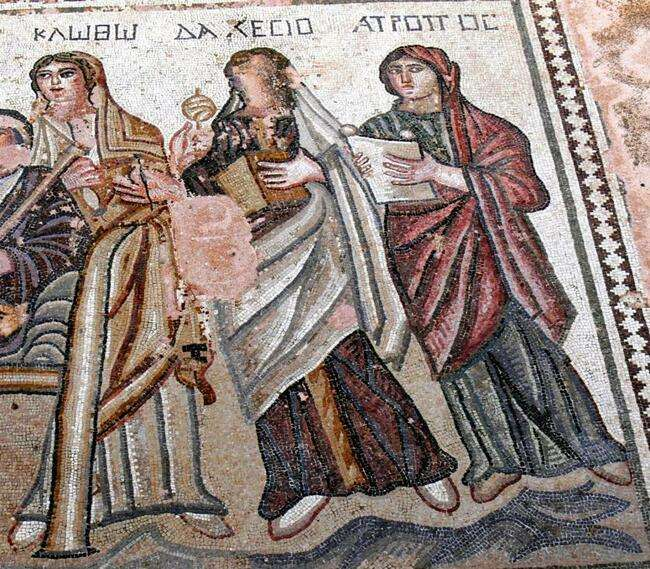

Di seguito Ananke e le parche, Lachesi, Cloto e Atropo attorno alla colonna. Una gira il fusaiolo del presente Cloto, Atropo del futuro e Lachesi del passato.

In un bassorilievo si può notare la moira Lachesi che, su un mondo, sostenuto da una colonna, tiene in mano un foglio (il destino), mentre Cloto fila e Atropo taglia il filo.

Vediamo ancora le Parche ritratte in un mosaico.

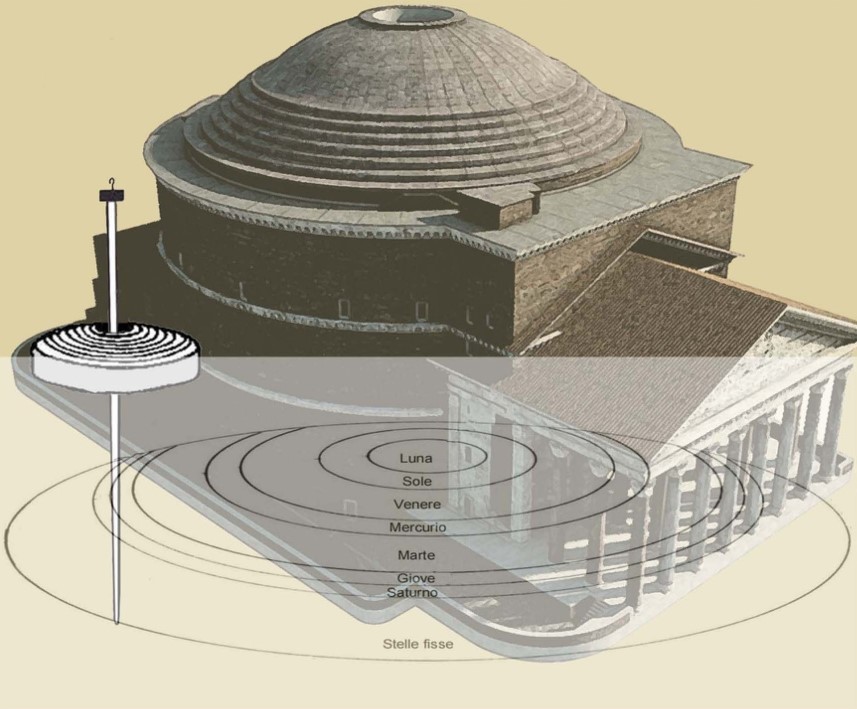

Detto dell’axis mundi e delle parche, parliamo degli otto cieli e della da noi ipotizzata similitudine col Pantheon.

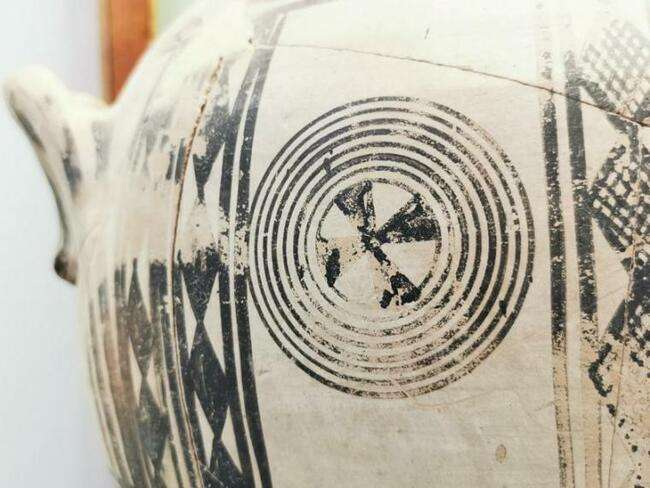

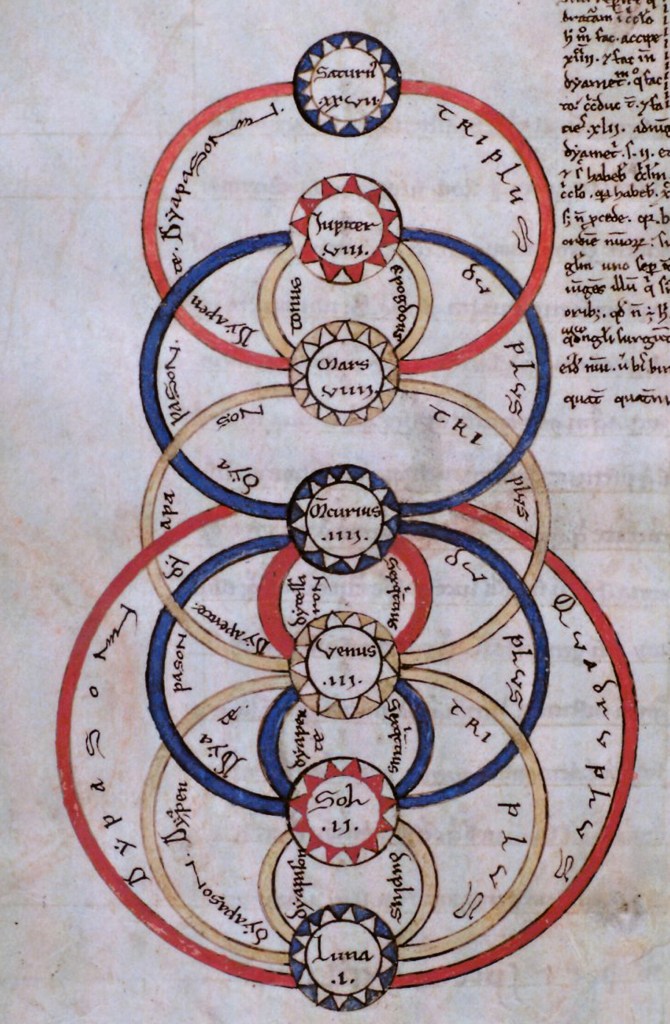

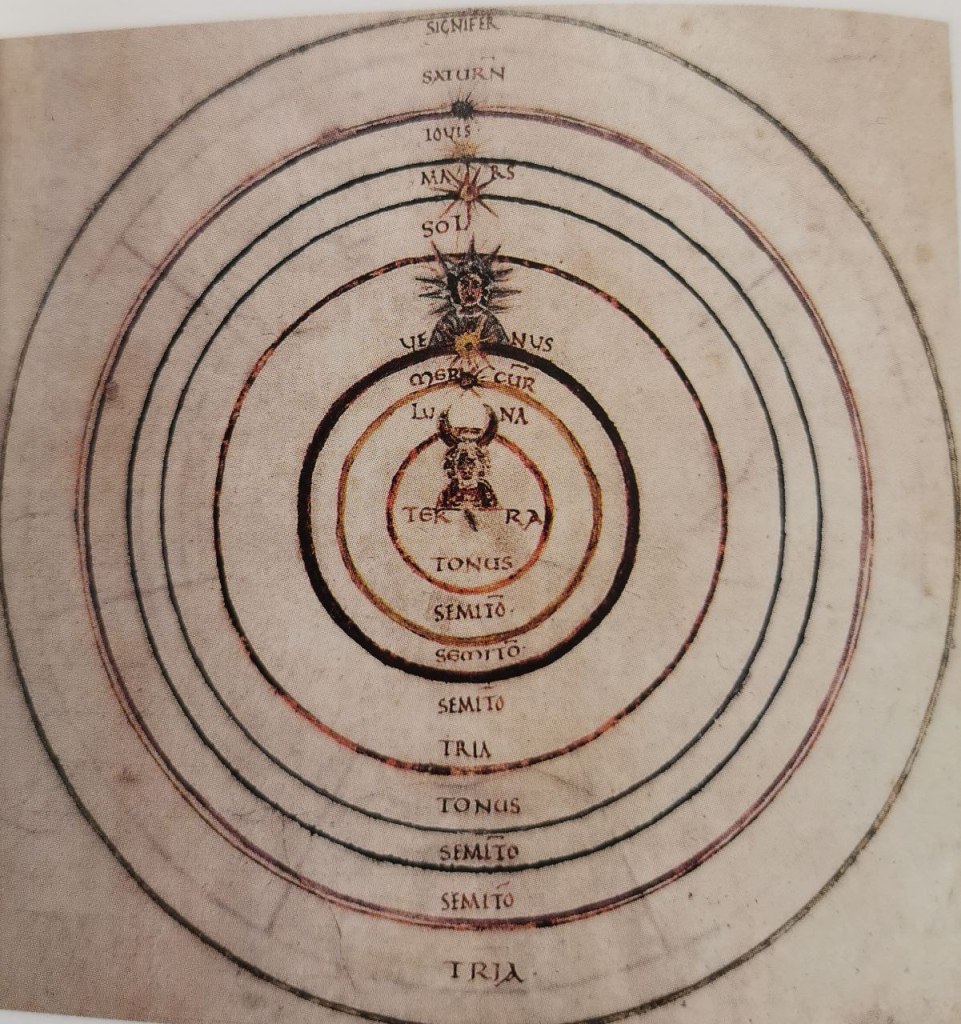

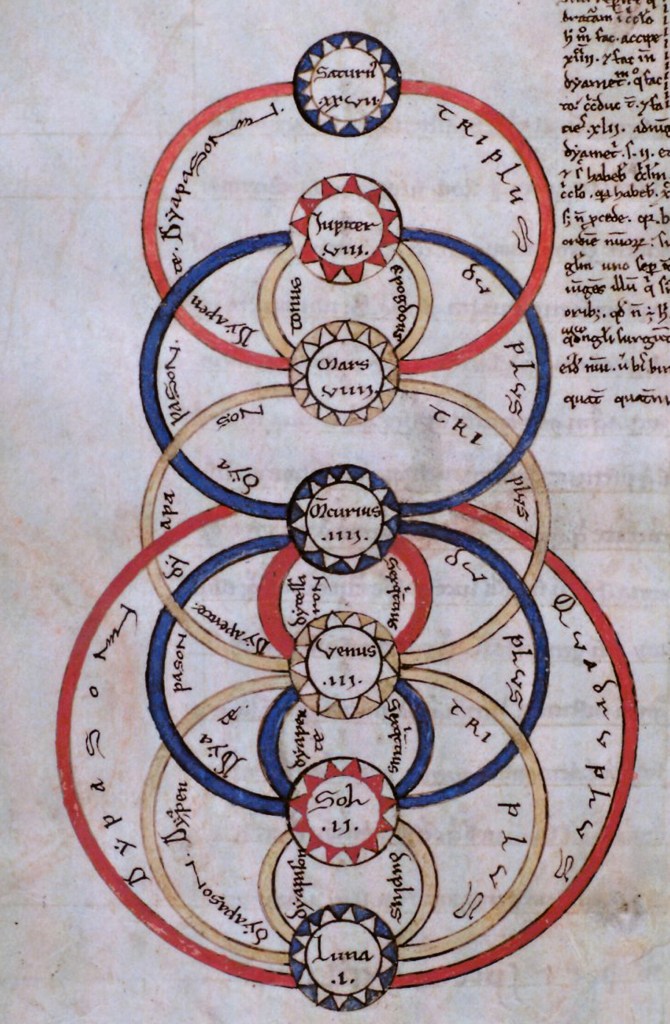

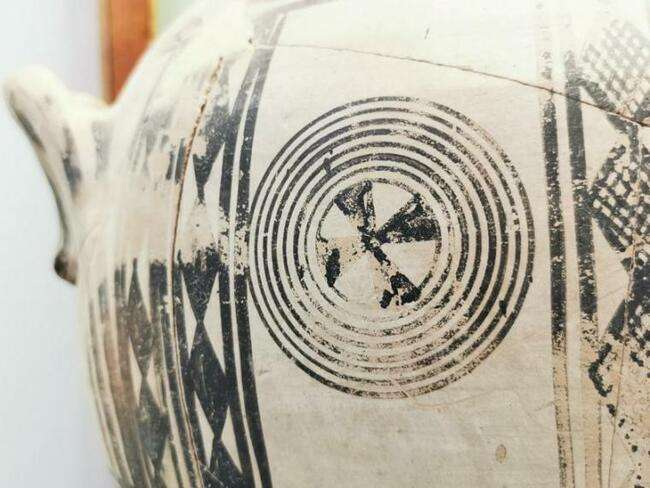

Qui vediamo un vaso riproducente i sette cieli planetari (spazi bianchi), con al centro una terra ritratta a forma di croce. Il vaso risale al nono secolo avanti Cristo.

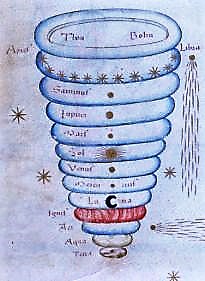

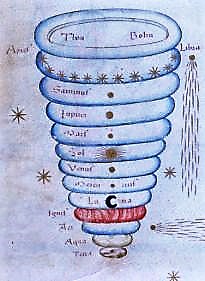

Di seguito una simile riproduzione medievale dei cieli del mondo. Dopo l’atmosfera e l’area del fuoco, si vedono i sette cieli planetari seguiti dall’ottava sfera stellare.

Per avere una visione della concezione del mondo visto lateralmente è utile la riproduzione di Fazio degli Uberti, nel Dittamondo: sopra la terra, vediamo l’acqua, l’aria, il fuoco, le otto sfere e l’empireo. La visione laterale presenta dunque una piramide o una cupola rovesciata.

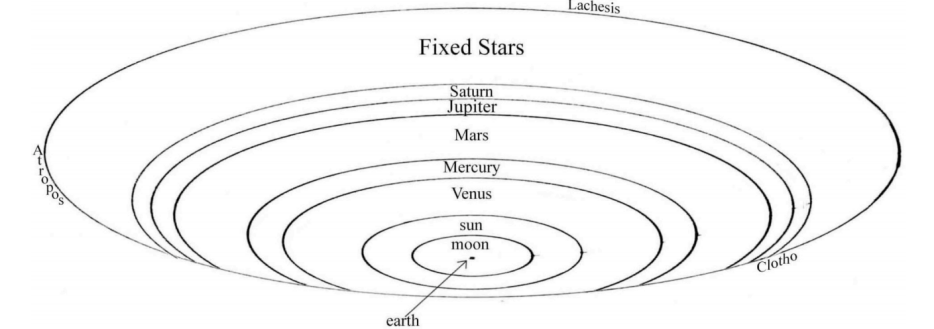

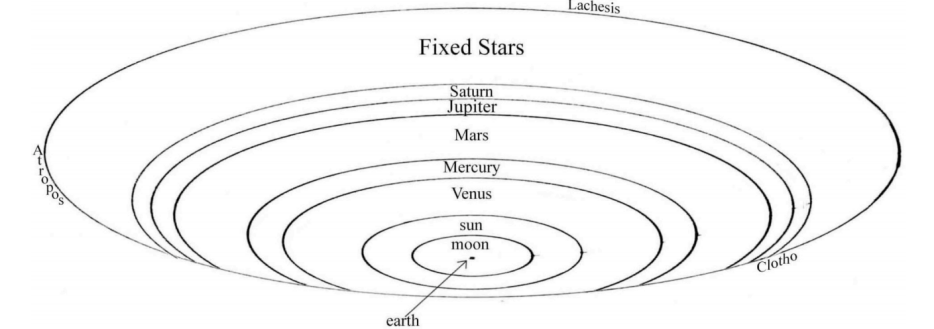

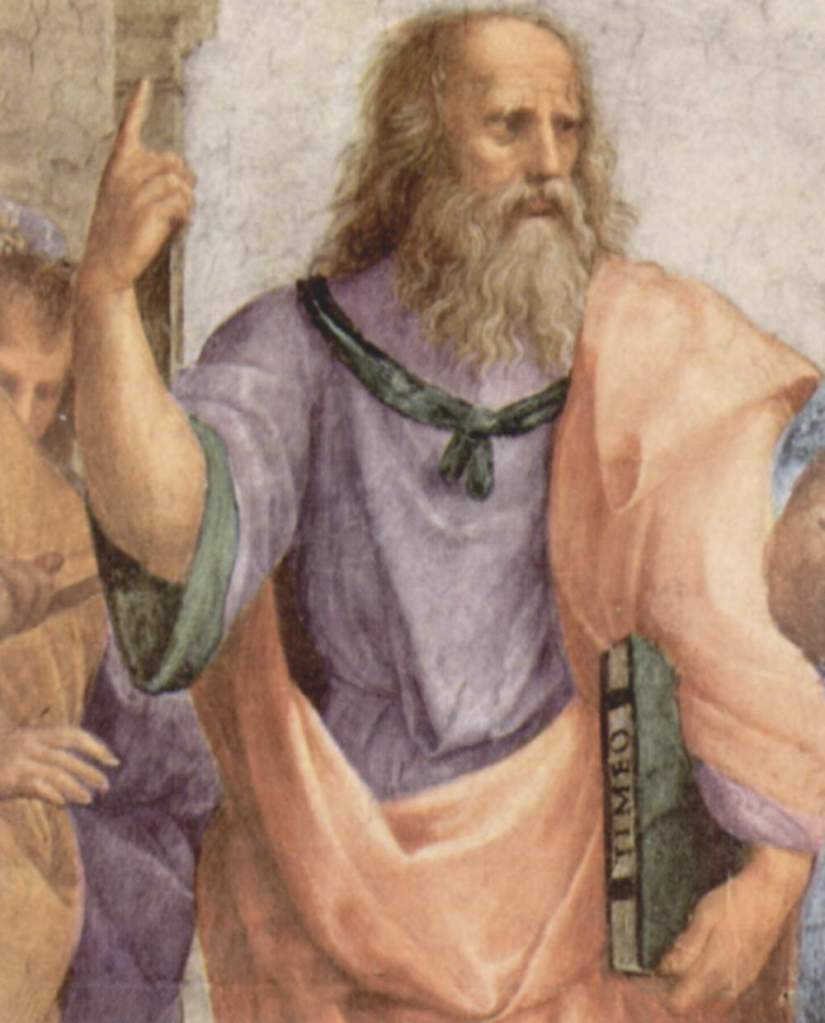

Simile rappresentazione degli otto cieli e degli otto fusaioli platonici è stata offerta da un matematico che ha provato a rappresentare i rapporti armonici e matematici tra gli astri, esposti da Platone nel mito di Er e nel Timeo. Tale studioso, Newsome, reinterpreta matematicamente gli astri di Platone e indica anche le 3 parche che girano i rispettivi fusaioli ovvero le sfere degli astri.

Come visibile dopo il fusaiolo della luna, in cui era conficcato l’axis mundi attorno a cui girava il cielo, stava quello del sole: tale disposizione astrae era quella antica, tipica degli egizi e di Platone. Successivamente in epoca più tarda prevalse la concezione caldea che metteva invece il sole in posizione centrale rispetto agli astri.

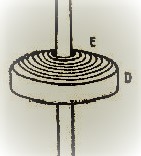

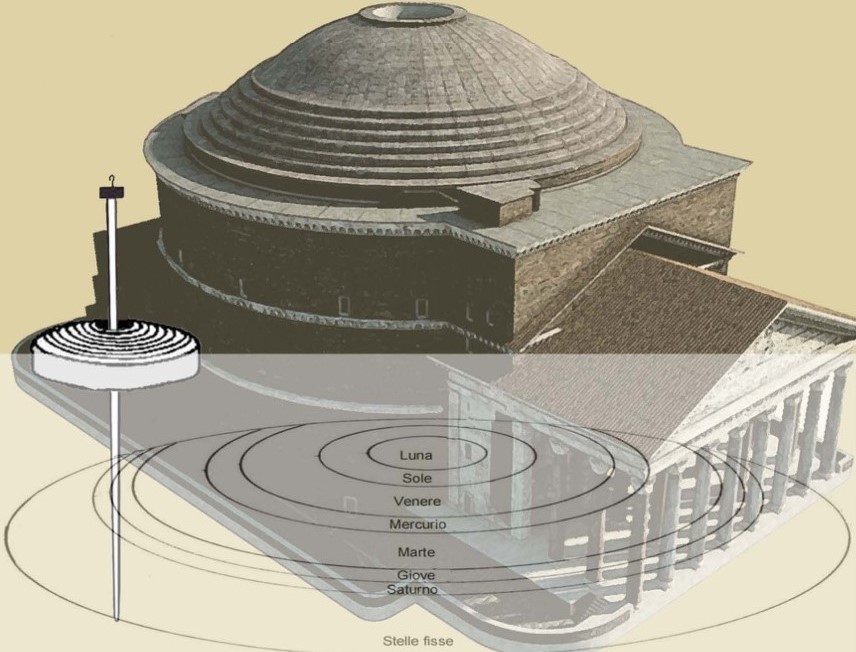

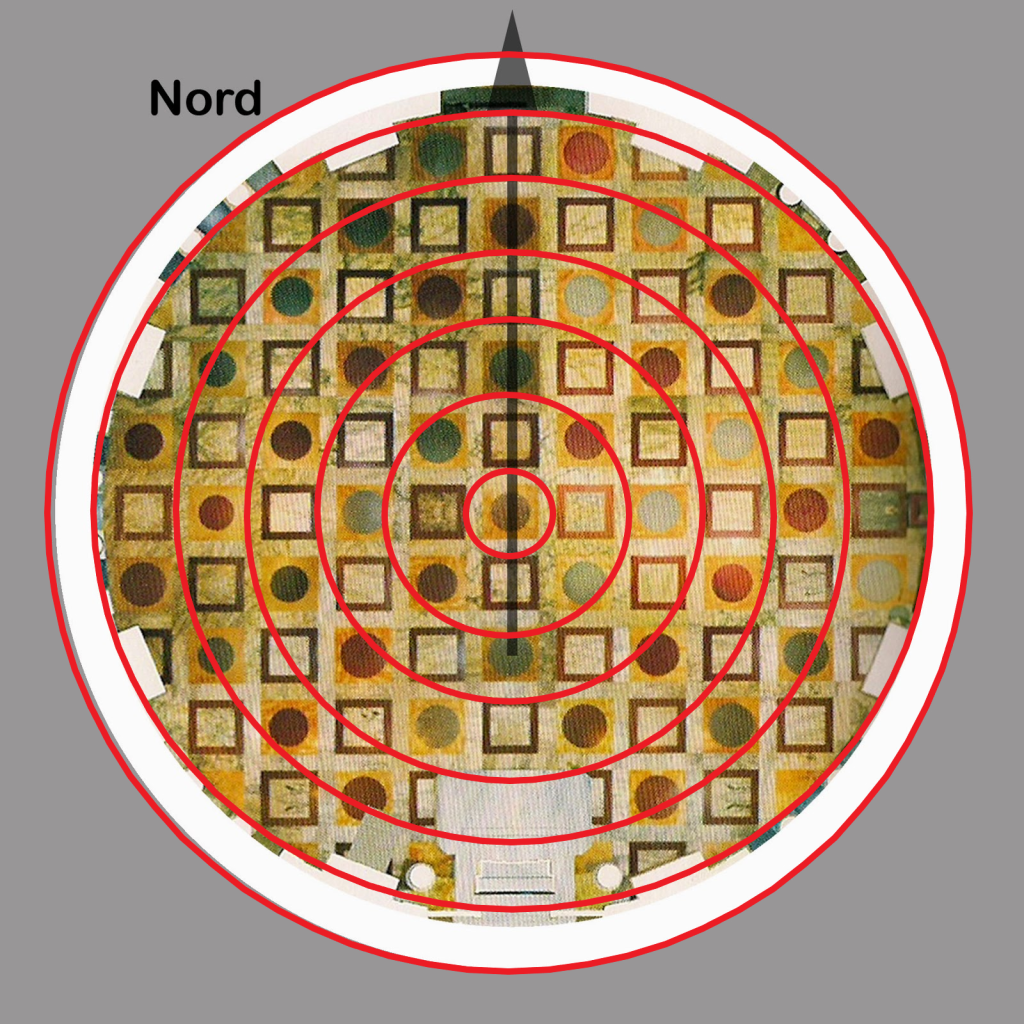

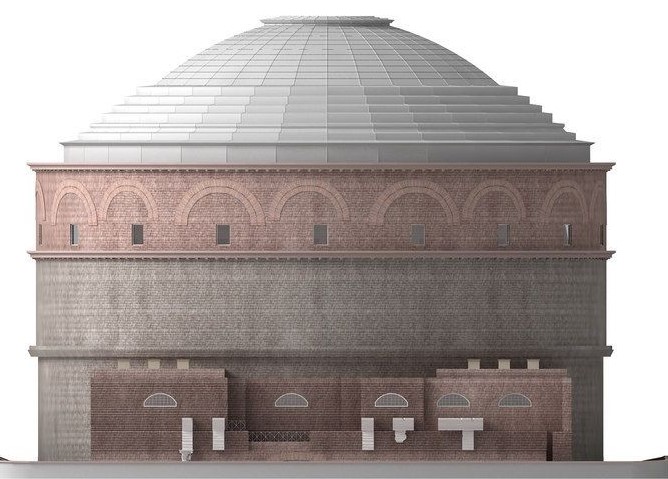

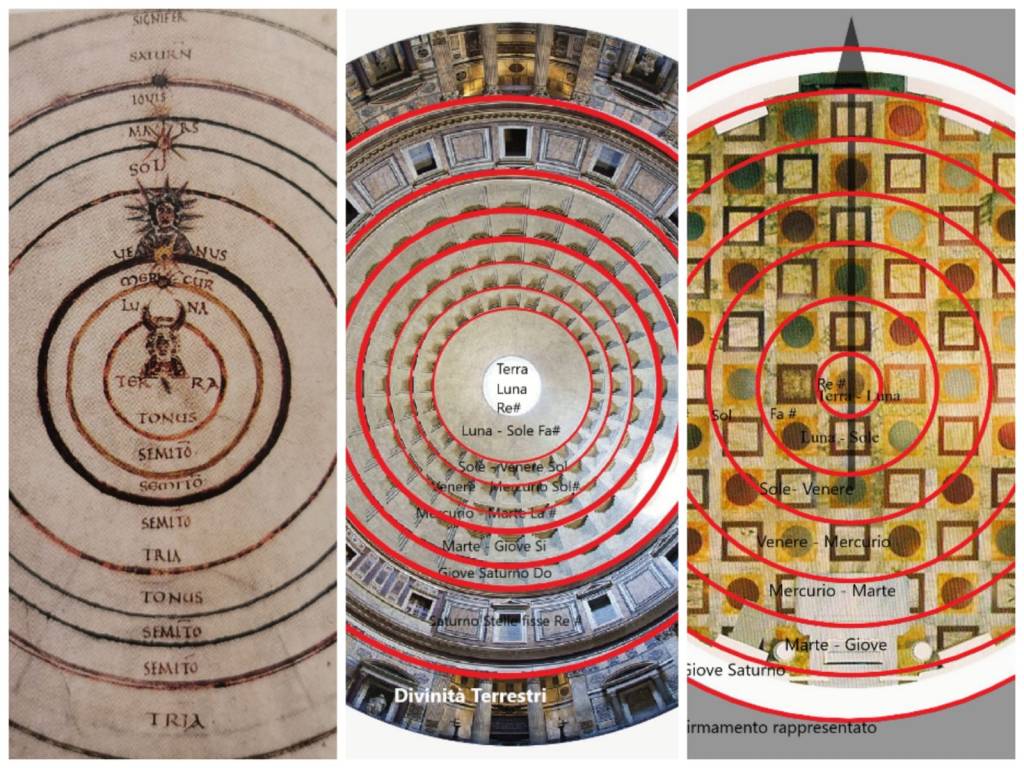

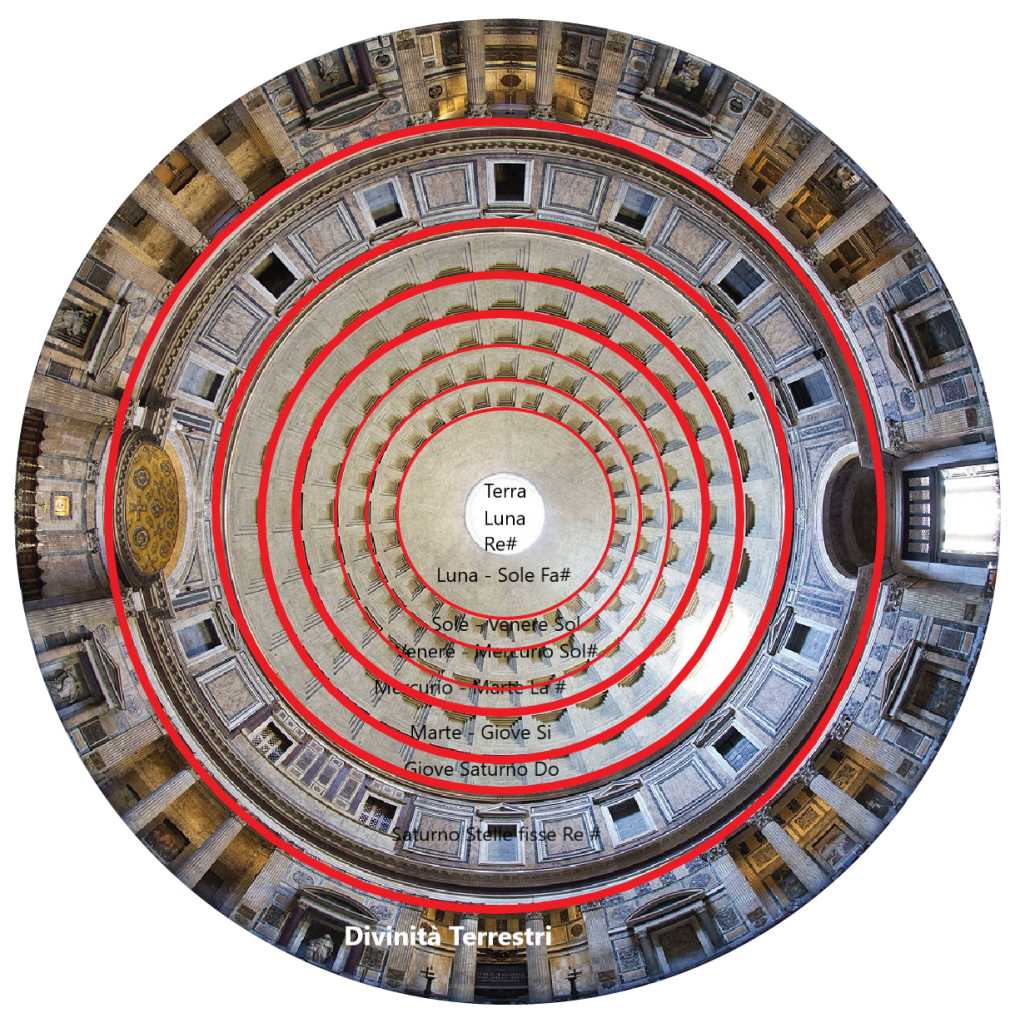

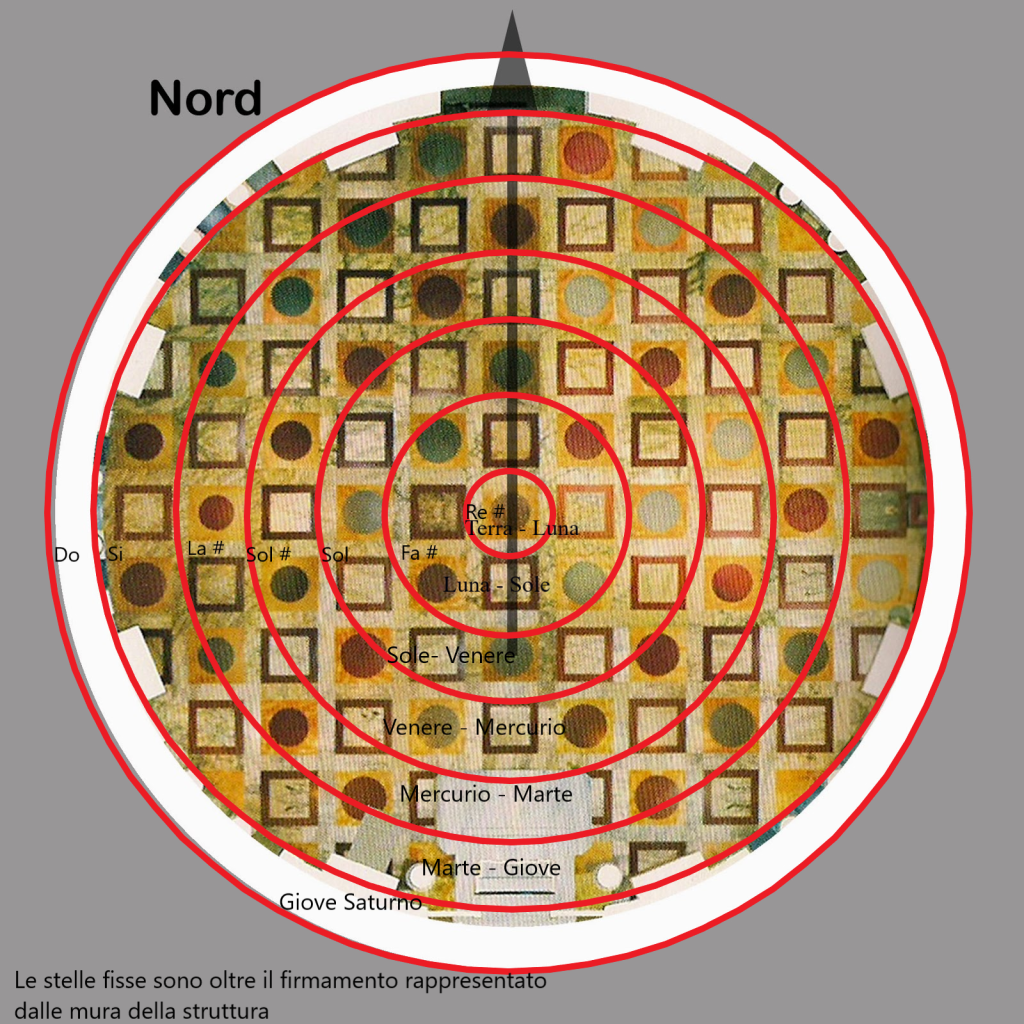

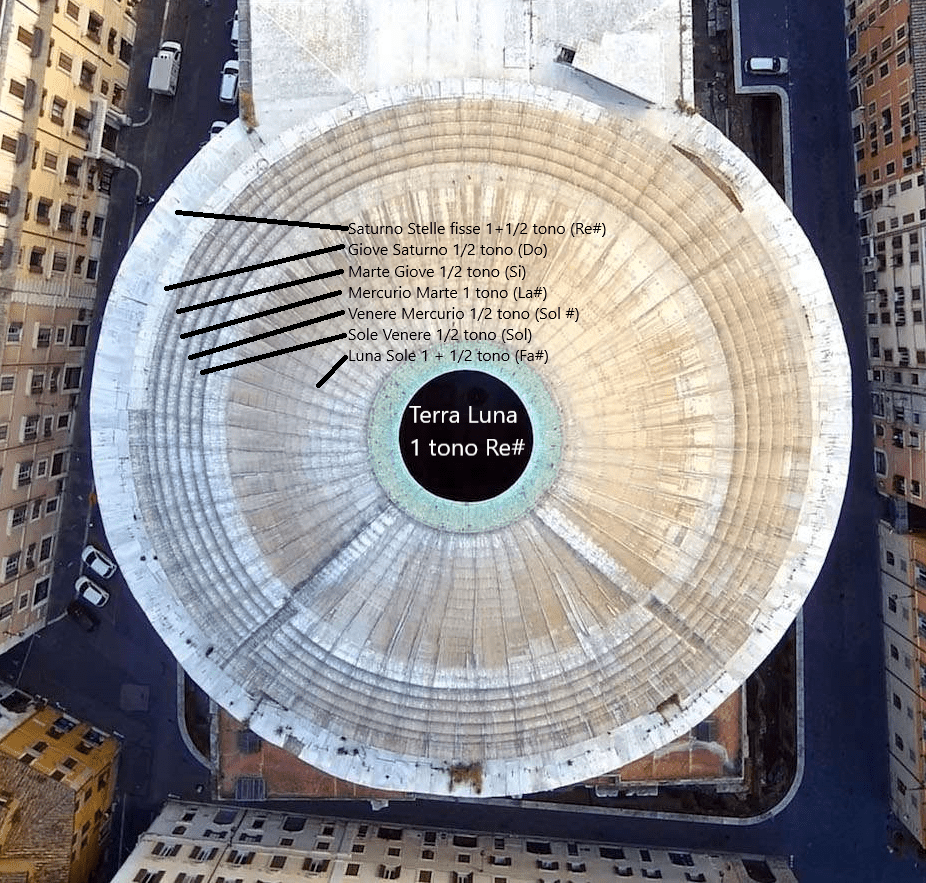

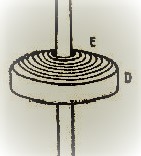

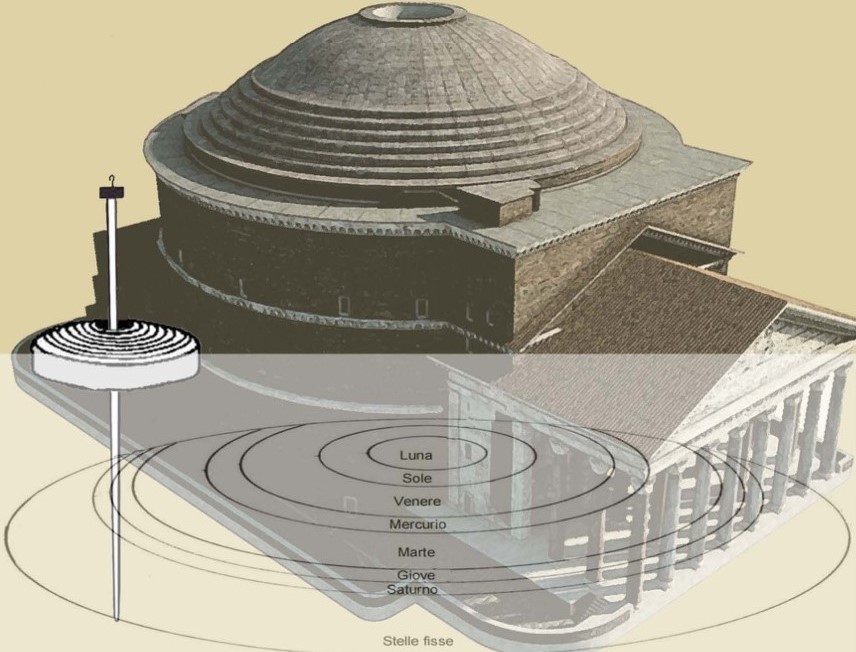

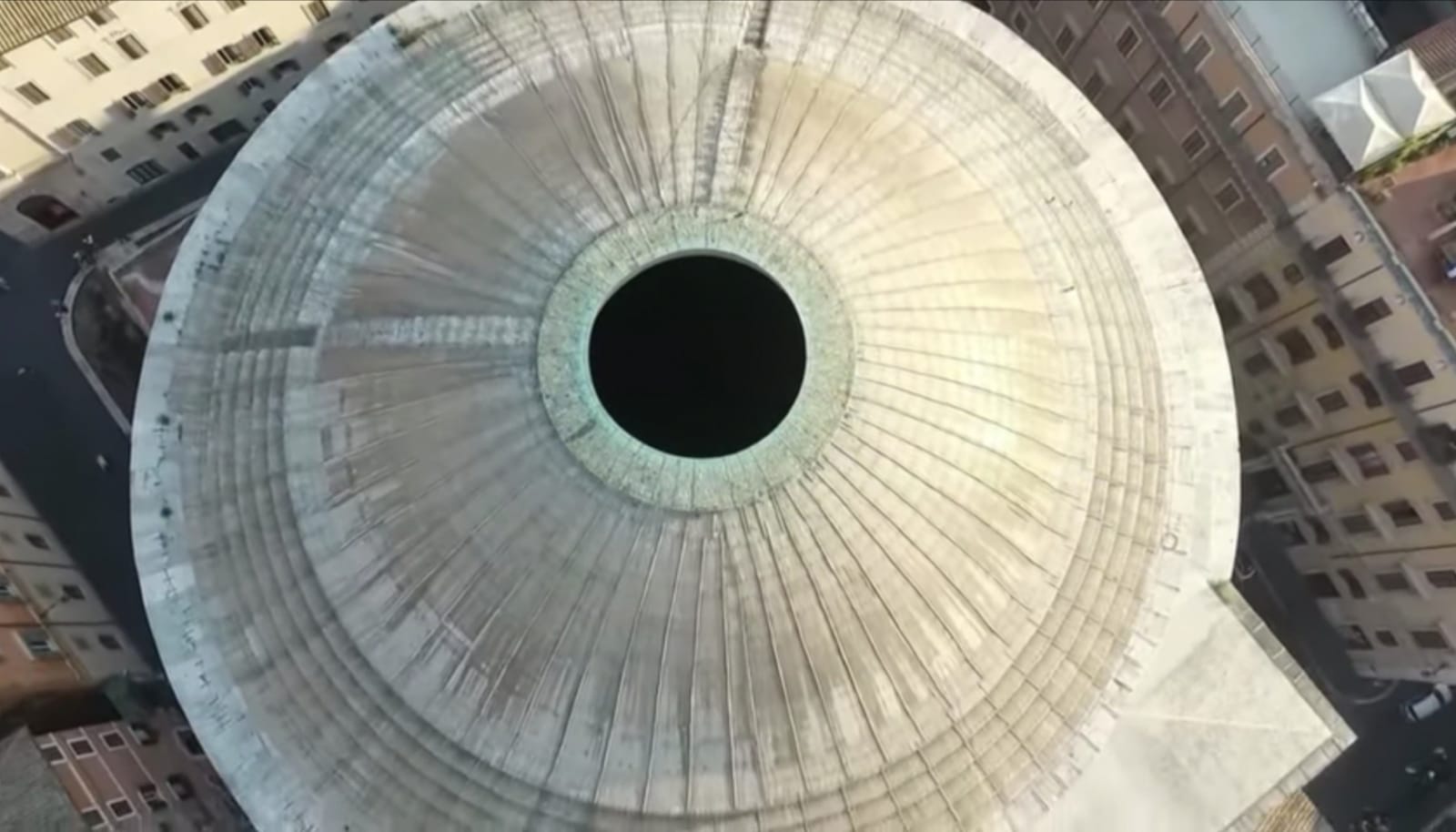

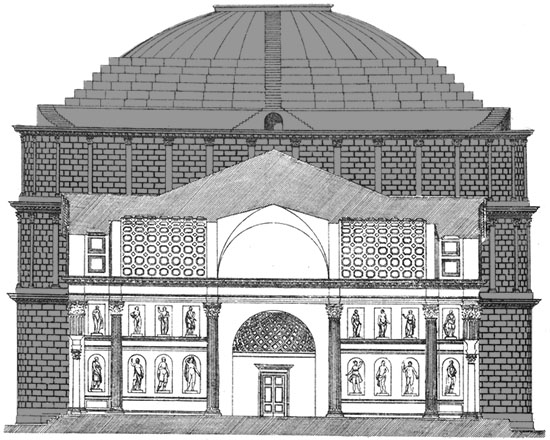

Se si capovolge la figura del Newsome, con stupore, possiamo notare che tale figura è perfettamente e incredibilmente speculare alla cupola superiore del Pantheon.

Ovviamente per ovvi motivi statici i costruttori scelsero di capovolgere i fusaioli, poiché una cupola o piramide rovesciata ben difficilmente avrebbe resistito a tempo e terremoti.

Di seguito una rappresentazione artistica dei fusaioli inseriti nella colonna di luce (axis mundi) del mito di Er platonico.

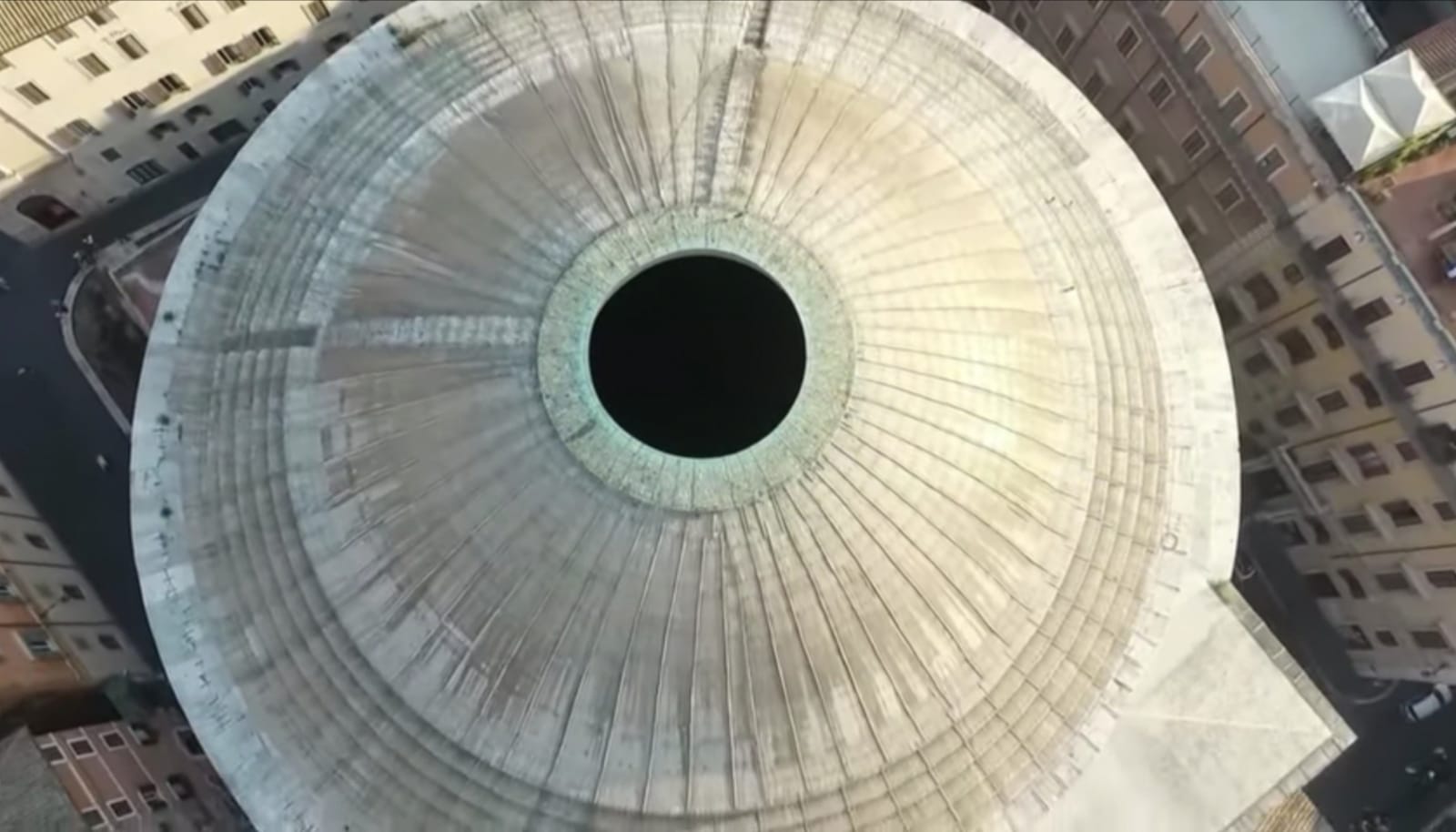

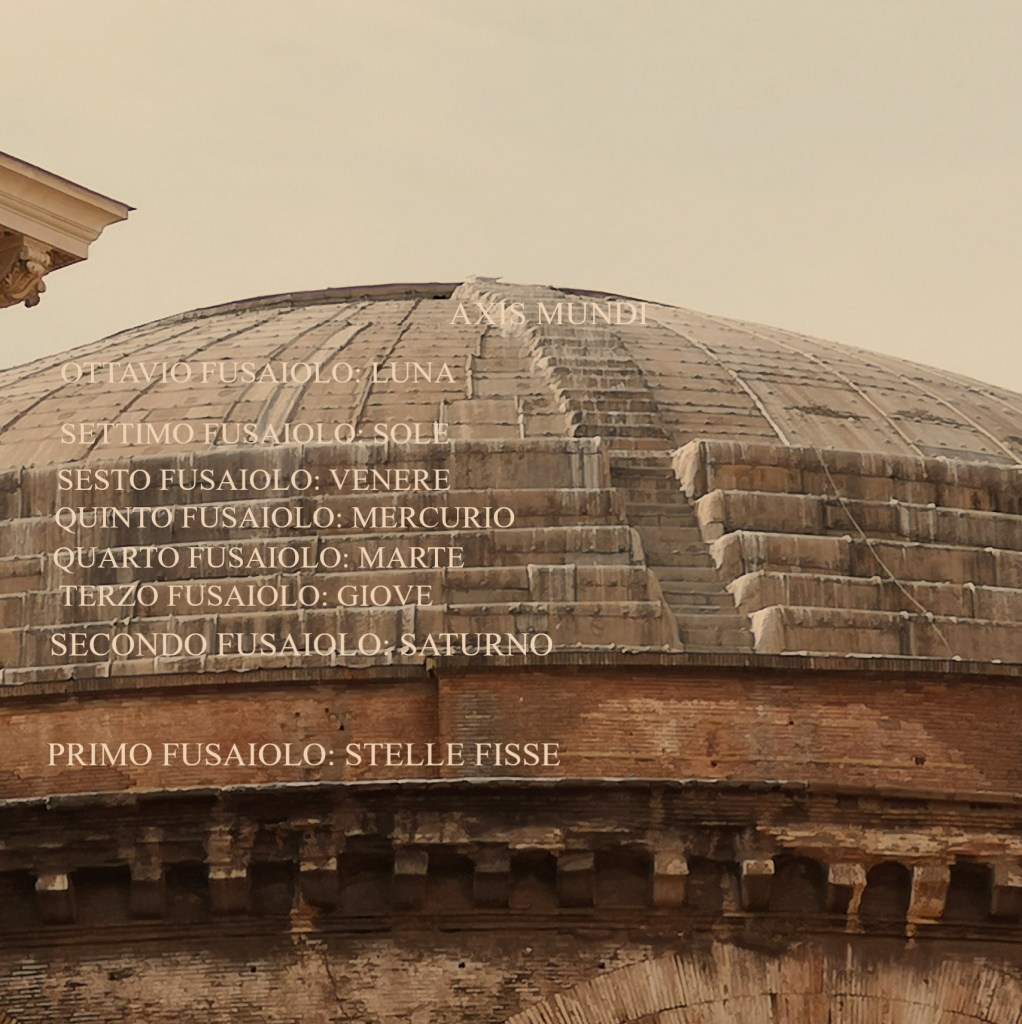

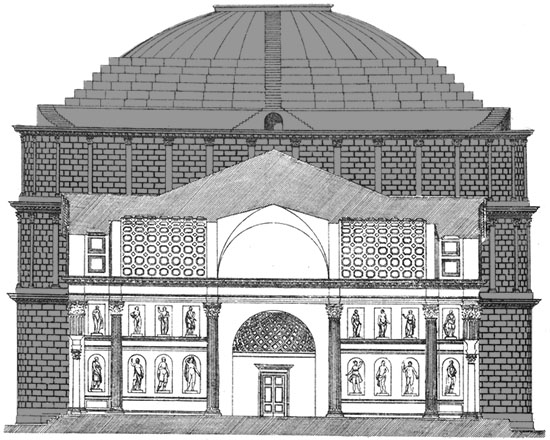

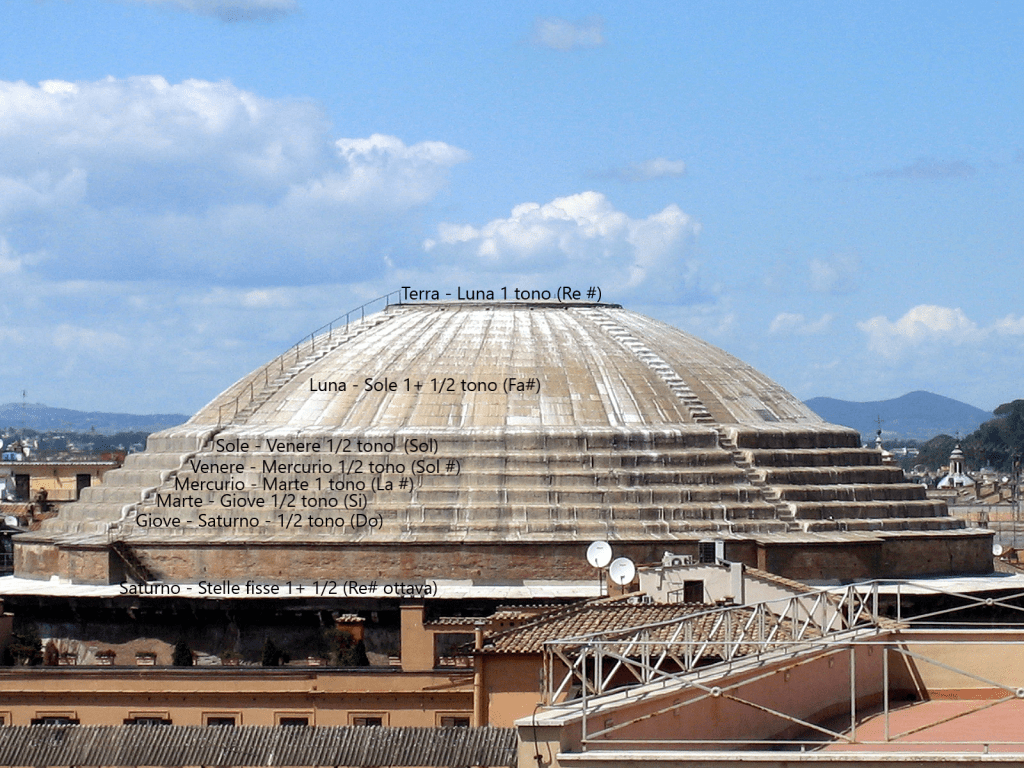

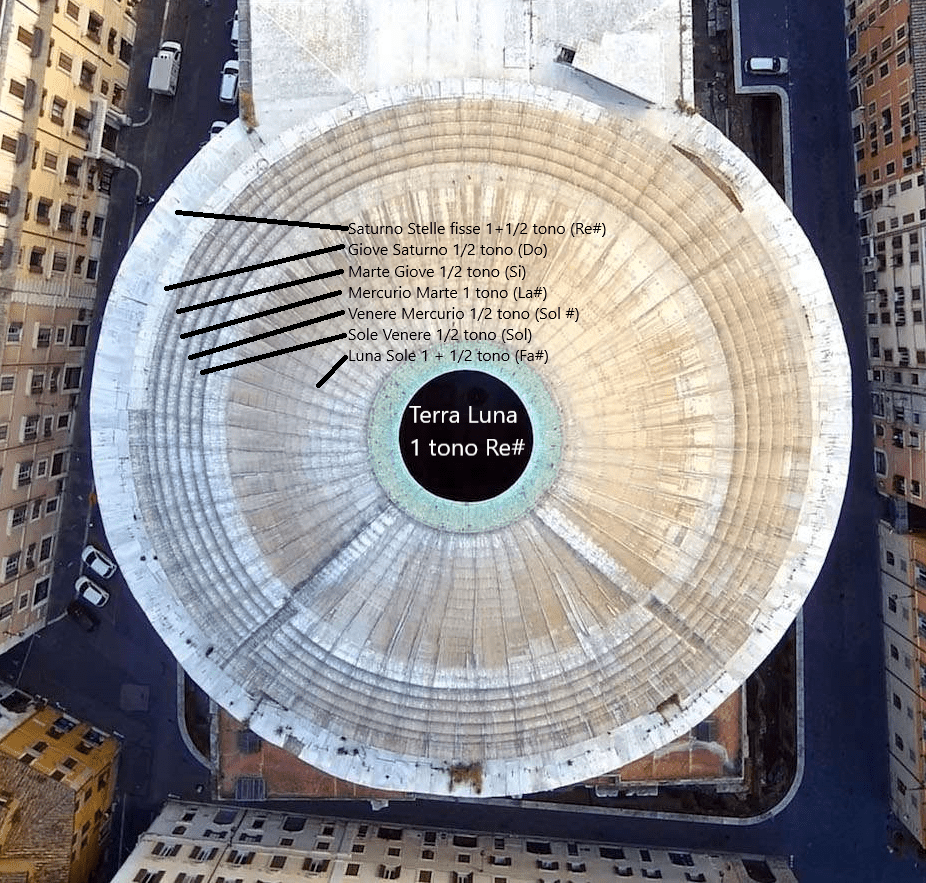

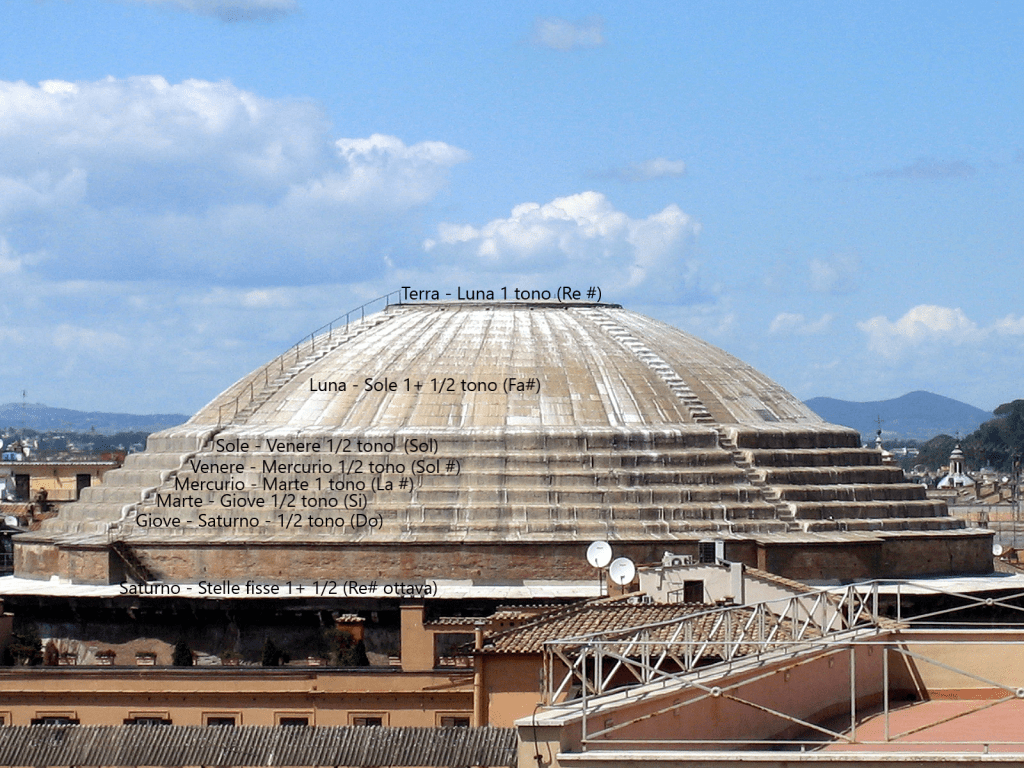

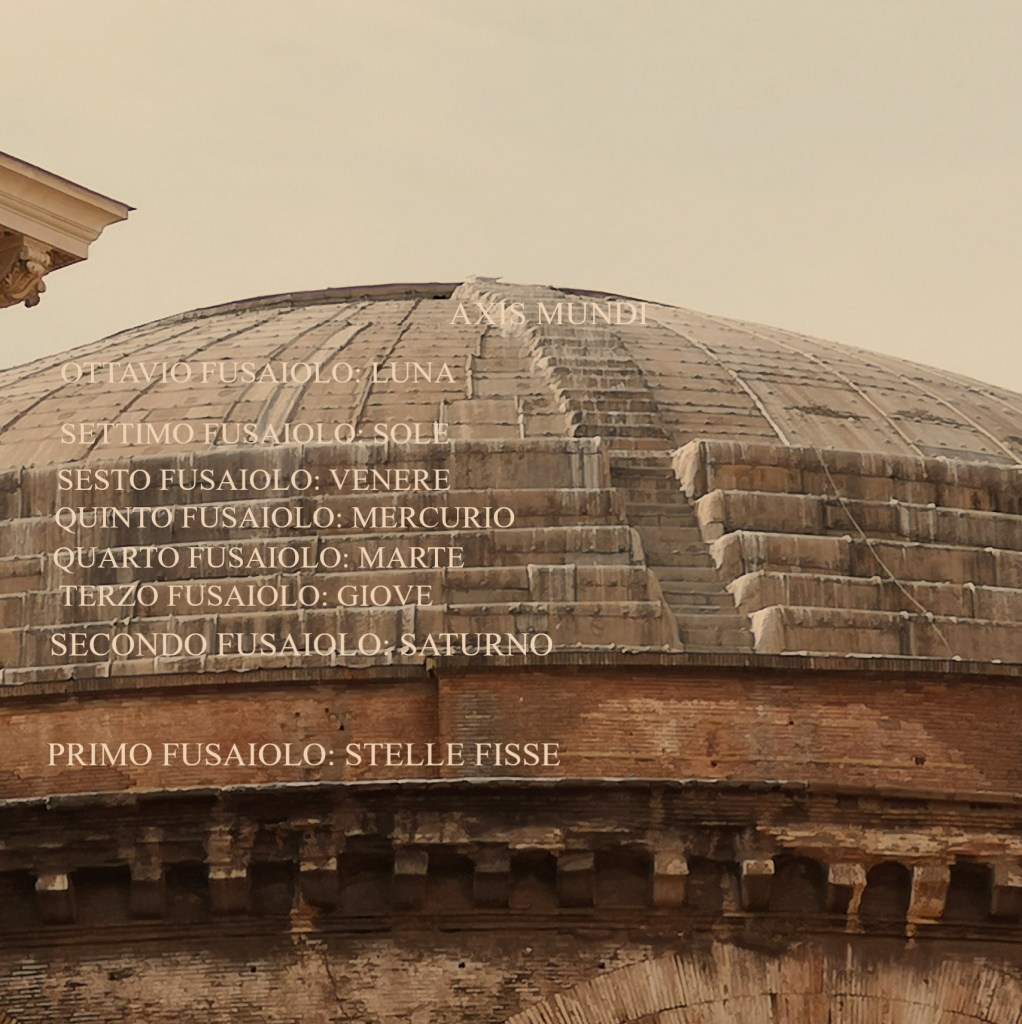

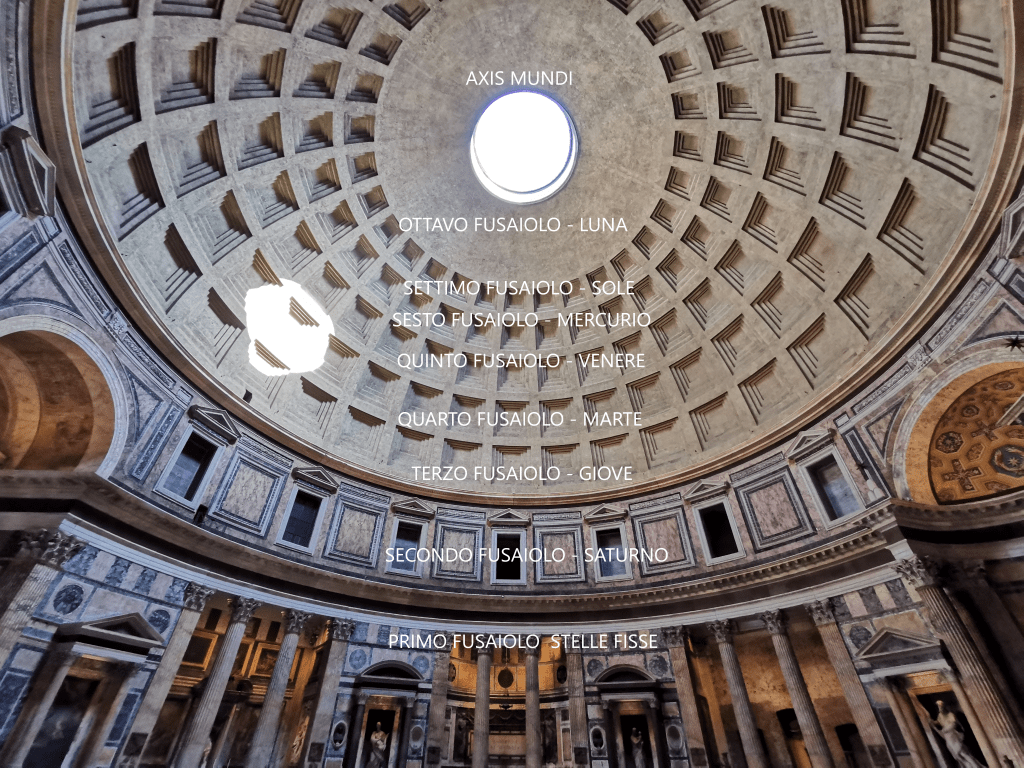

In questa foto si possono apprezzare gli otto fusaioli visti dall’esterno del pantheon e l’axis mundi in alto. L’ultimo fusaiolo, ovvero la prima fascia prima dei gradoni, è quello dell’ottava sfera ovvero delle stelle fisse, il primo fusaiolo, dopo quello di Saturno, poi Giove, Marte, Mercurio, Venere Il fusaiolo attorno all‘oculus (axis mundi) è quello della Luna.

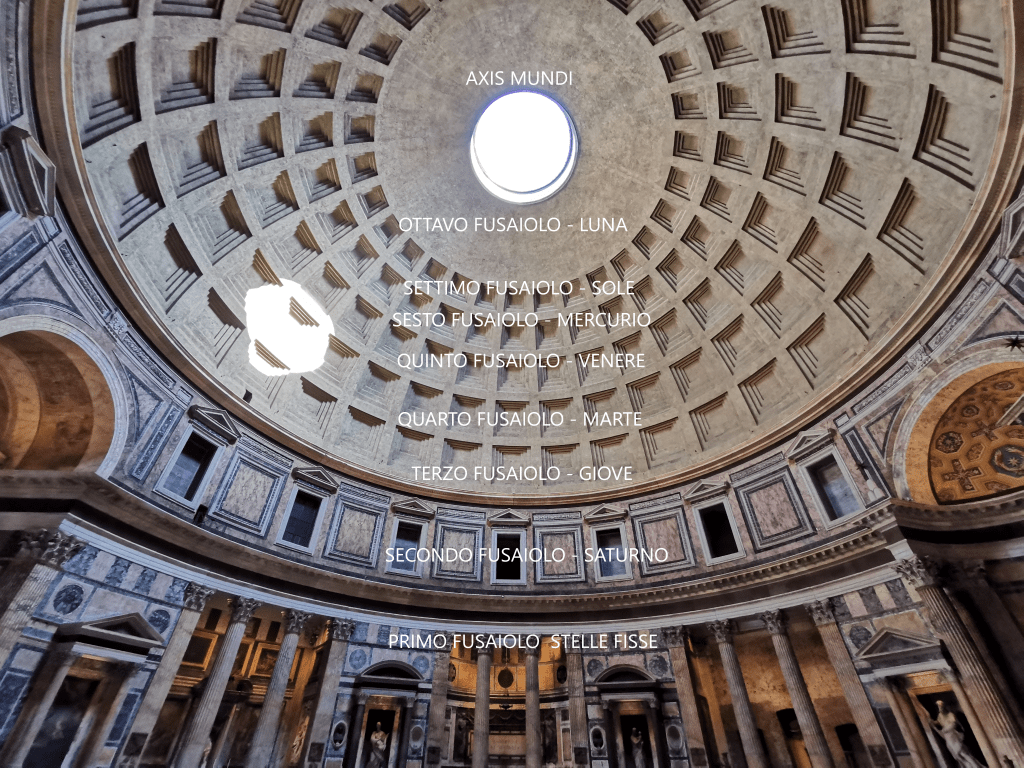

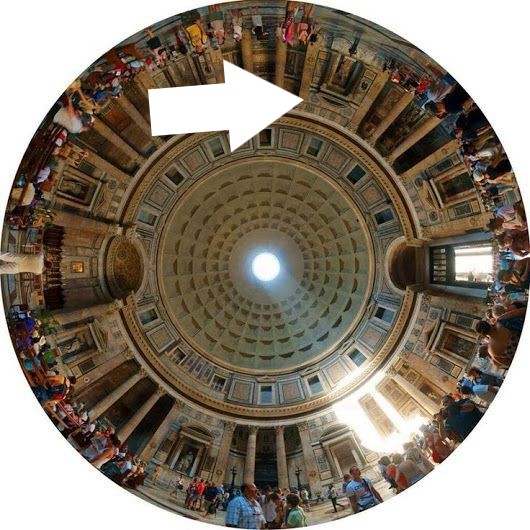

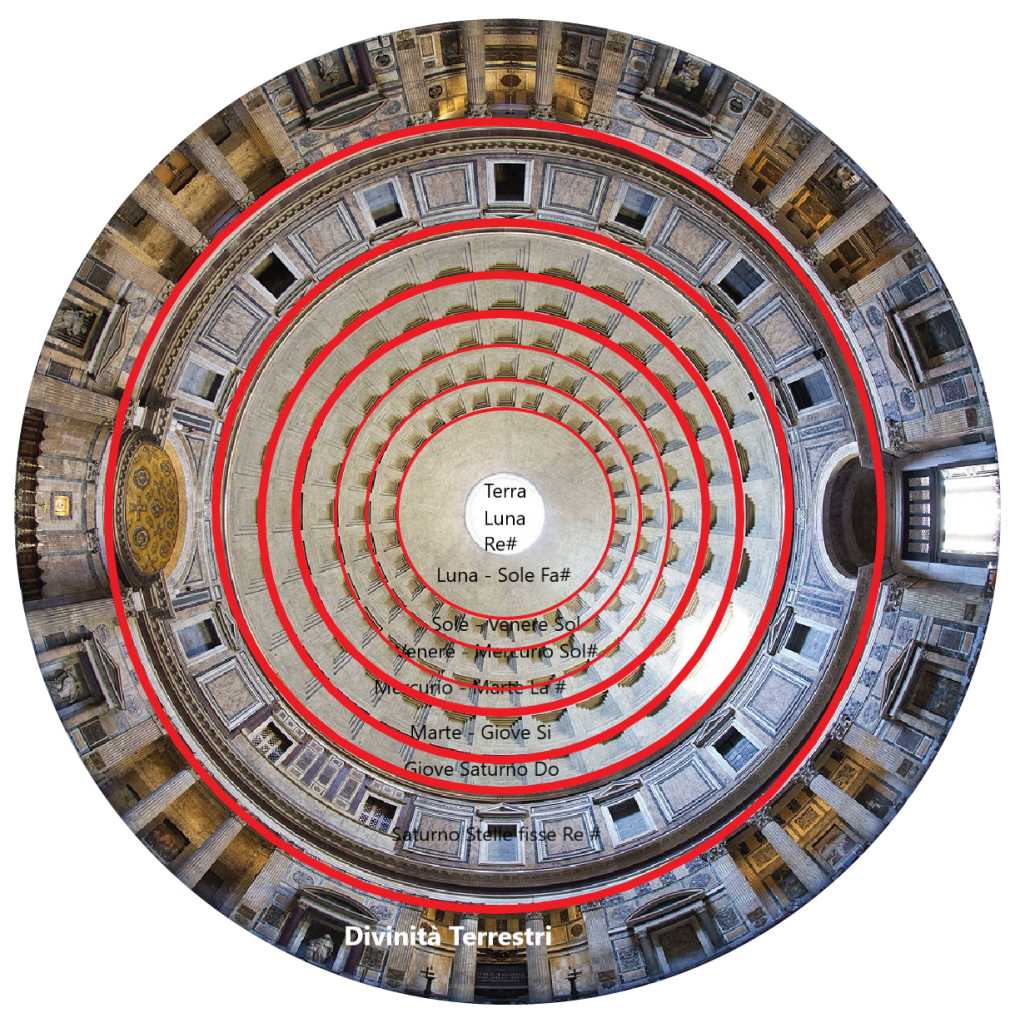

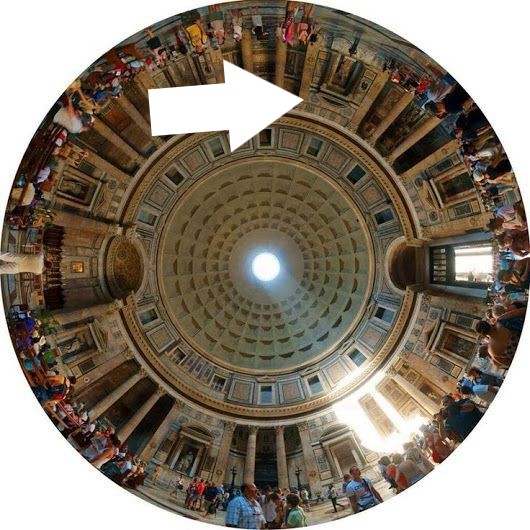

Vediamo ora come si sono resi architettonicamente i fusaioli all’interno.

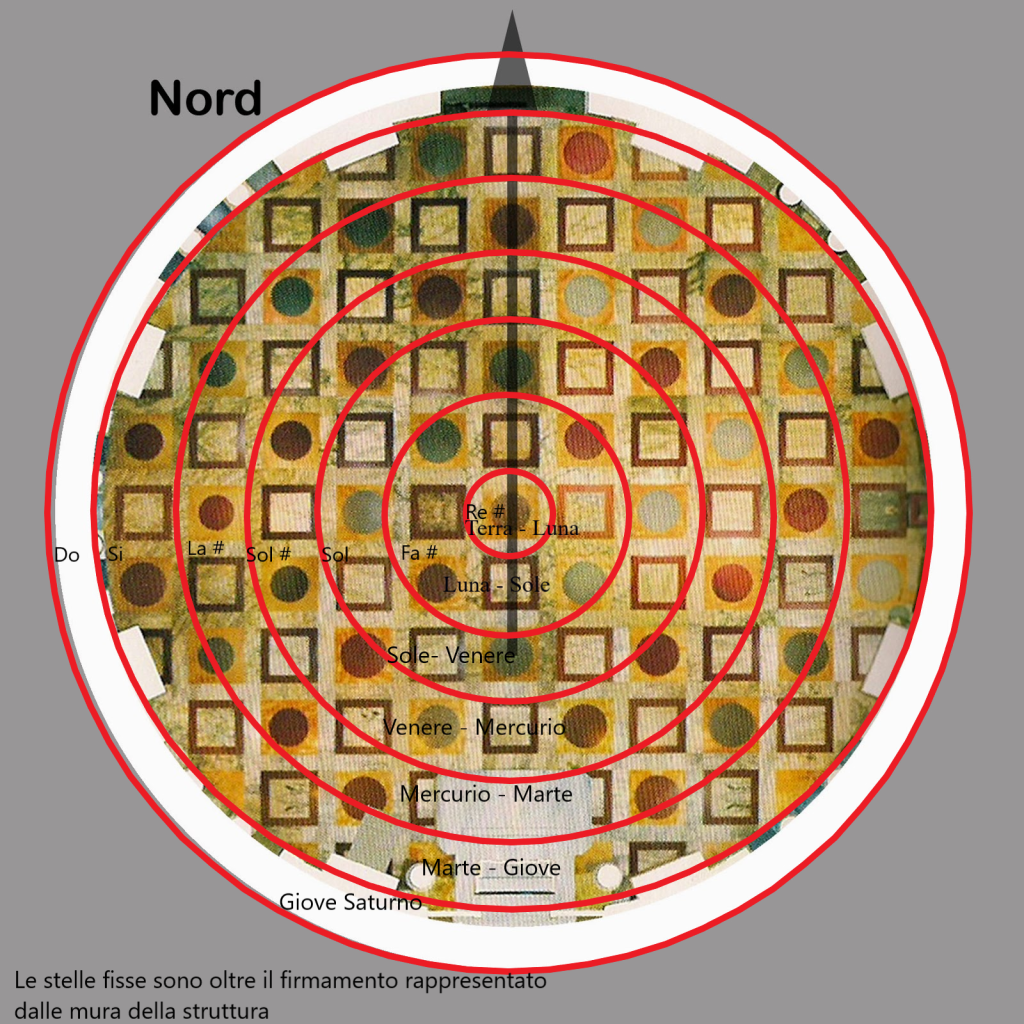

L’ottavo fusaiolo, stelle fisse, era a pianterreno ed era limitato sotto dal pavimento e sopra dalla cornice dell’imposta. Il secondo fusaiolo di Saturno era all’imposta. Con il fusaiolo di Giove cominciavano le fasce di 28 cassettoni per fascia (28 sono le case lunari), seguito da Marte, Mercurio, Venere, Sole e Luna, quest’ultima, per ovvi motivi, senza case lunari, al cui interno, come detto, stava l’asse del mondo.

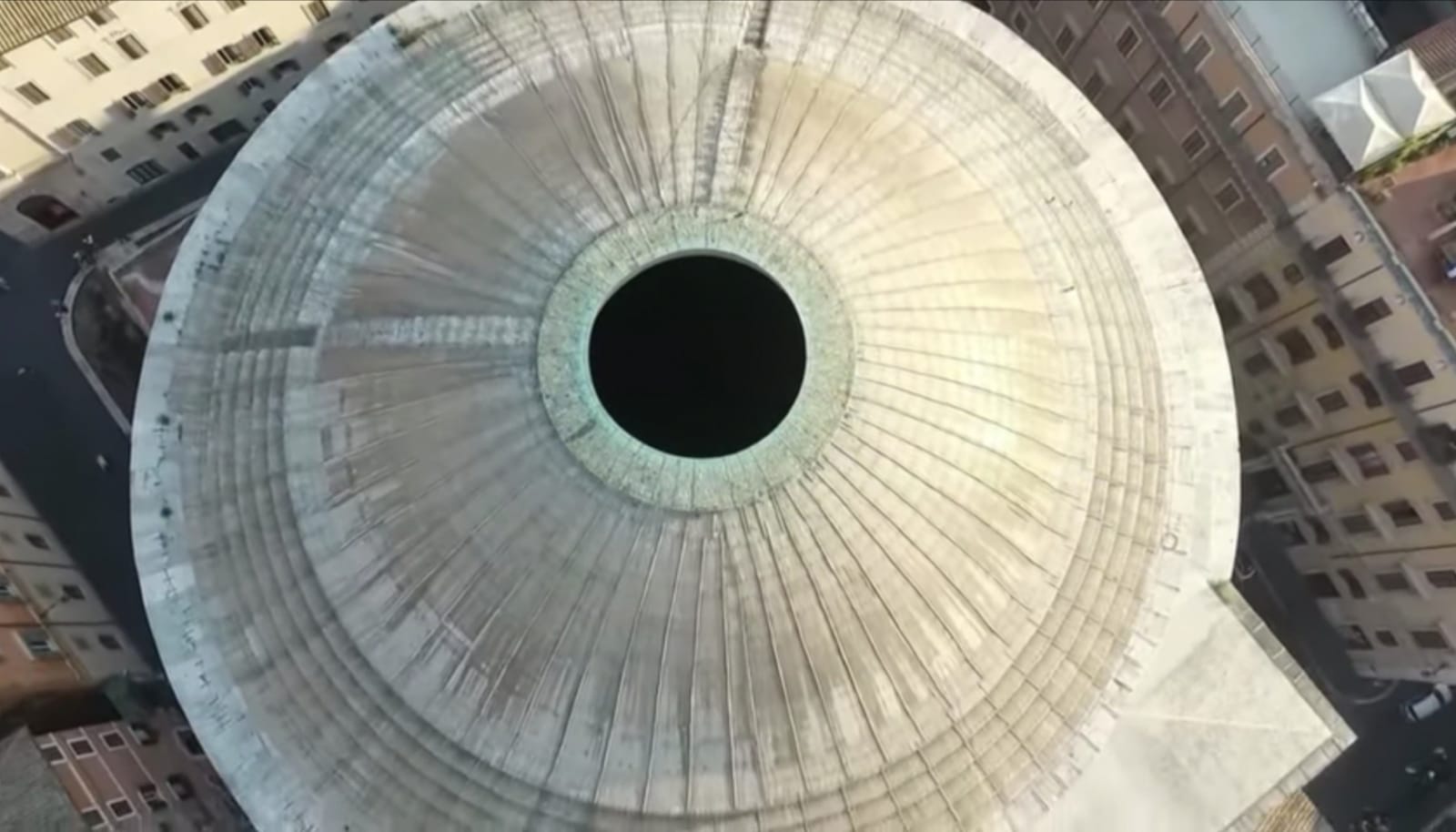

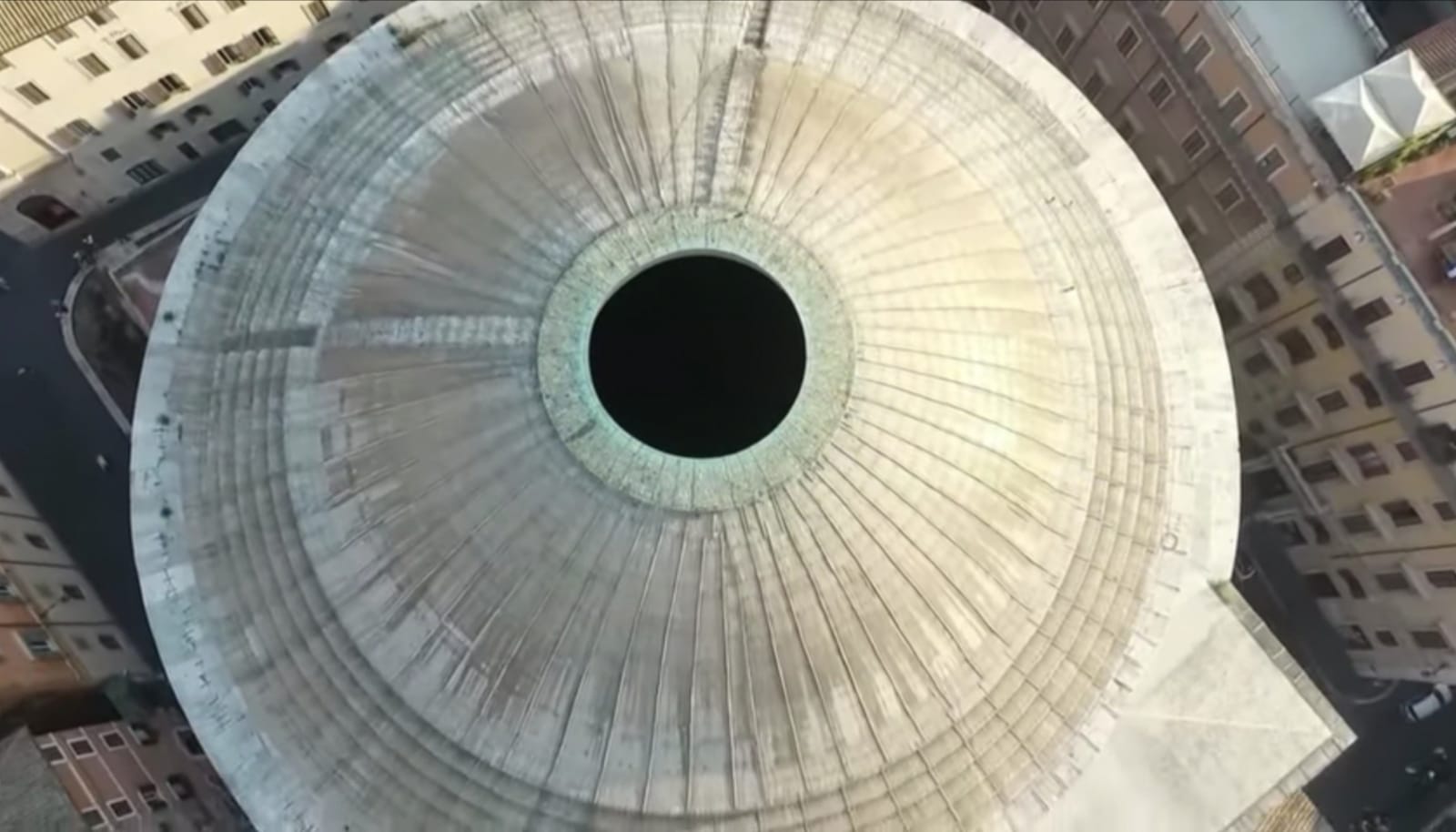

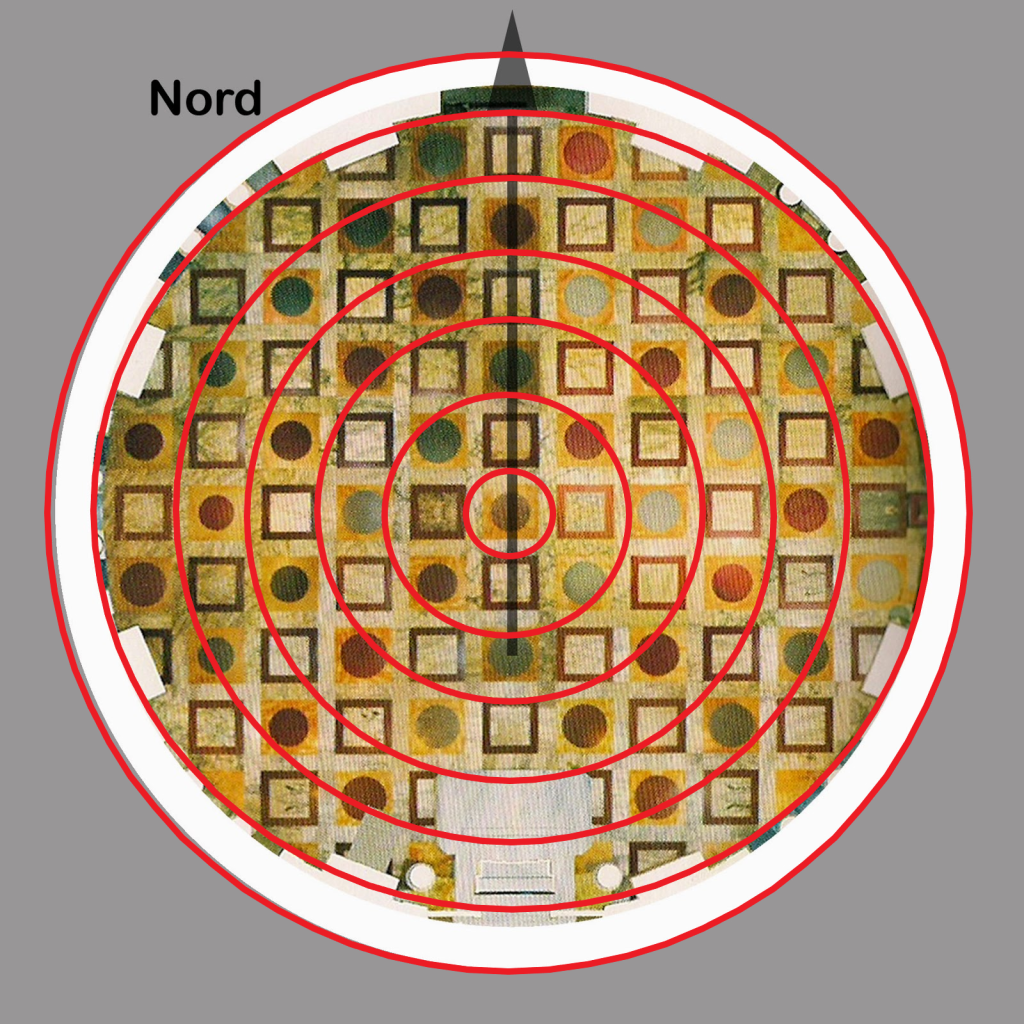

Nella visione dall’alto della cupola del Pantheon si nota l’ottavo fusaiolo (stelle) sulla circonferenza e il primo fusaiolo attorno all’oculus (axis mundi) quello della Luna.

Trattiamo ora della religione del Mondo e il Pantheon.

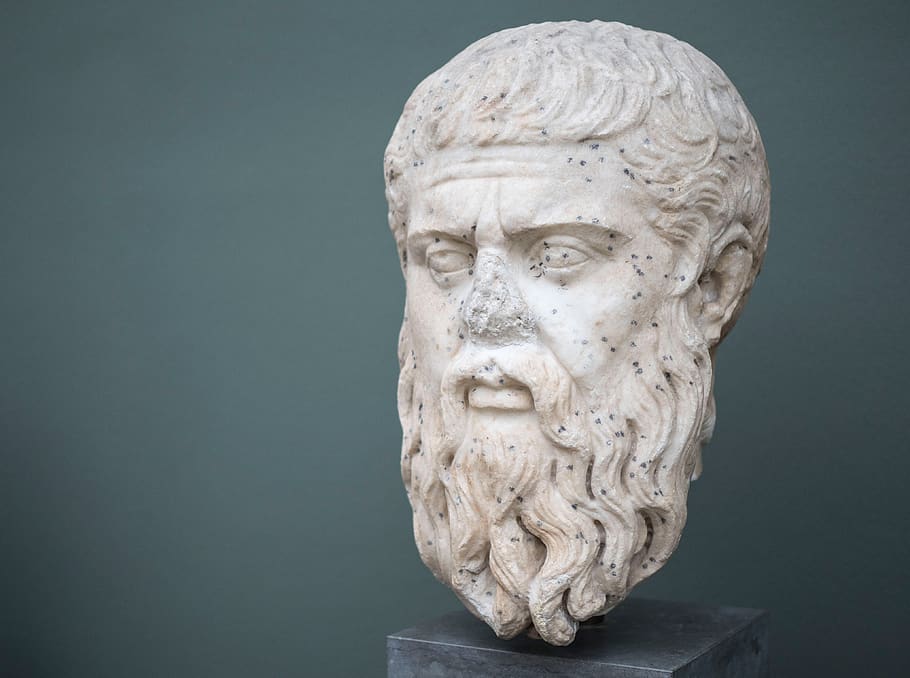

La religione cosmica di Platone (dal greco cosmos ornamento ovvero mundus in latino) ipotizziamo sia stata riprodotta nel Pantheon.

Cosa determina tale intuizione? Il fatto che come detto il Pantheon raffigurasse, per le citate notizie di Ammiano Marcellino e di Dione Cassio, il cielo, la succitata riproduzione architettonica della concezione platonica dei fusaioli celesti e, infine, una notizia che riportiamo da un autore settecentesco, il Vasi: Questo maraviglioso tempio, secondo il sentimento comune, […] si disse Panteon, perché era dedicato a tutti li Dei immaginati da’ Gentili. Nella parte superiore […] erano collocate le statue delli Dei celesti, e nel basso i terrestri, stando in mezzo quella di Cibele; è nella parte di sotto, che ora è coperta dal pavimento, erano distribuite le statue delli dei Penati.

Dunque vi erano statue sotto il pavimento a rappresentare Ctonia.

Nella foto le nicchie per gli dei planetari di Urania nell’imposta e il pianterreno con le nicchie per gli Dei terrestri di Gaia.

Sull’imposta erano collocate, invece, statue delle sette divinità planetarie di Urania. Gaia (la Terra) era invece rappresentata dalle statue degli Dei terrestri al pianterreno del Pantheon, con in mezzo Cibele.

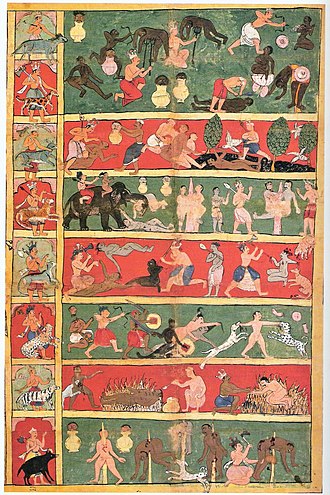

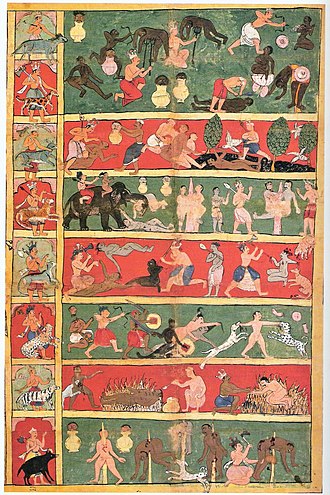

Qui vediamo il pavimento del Pantheon. Per ogni figura geometrica sono inscritte le sette fasce circolari dei sette piani ctoni, qui ritratti in un dipinto indiano del diciassettesimo secolo raffigurante i sette livelli dell’inferno giainista.

In corrispondenza, sopra il pavimento, stava la cupola interna divisa in sette fasce circolari.

Dopo Urania, Gaia e Ctonia cosa mancava per completare la celebrazione del mondo di Platone? L’oceano. Dove si trova? Dietro il Pantheon, ed era il tempio di Nettuno anch’esso realizzato da Agrippa.

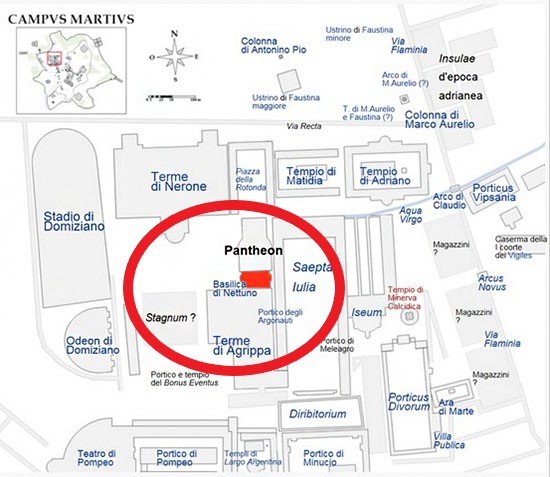

Vediamo qui una ricostruzione della basilica di Nettuno (Oceano), dietro il Pantheon. Nella immagine sulla sinistra si intravede lo Stagnum (che rappresentava l’acqua dolce di laghi e fiumi) e sulla destra il portico degli argonauti.

Nella foto vediamo fregi della basilica del dio Nettuno / Oceano.

Nell’immagine accanto vediamo riassunto il piano urbanistico di Agrippa dedicato al culto del Mondo: Pantheon, Basilica di Nettuno, portico Argonauti e Stagnum. Il Pantheon comprendeva le divinità uraniche, terrestri e ctonie. La basilica di Nettuno quelle oceaniche.

Di seguito una ricostruzione della Basilica del dio Nettuno con statue: dietro si vede il Pantheon. Si può notare la corrispondenza delle statue al pian terreno del tempio di Nettuno con quelle del Pantheon.

Accenniamo all’atmosfera.

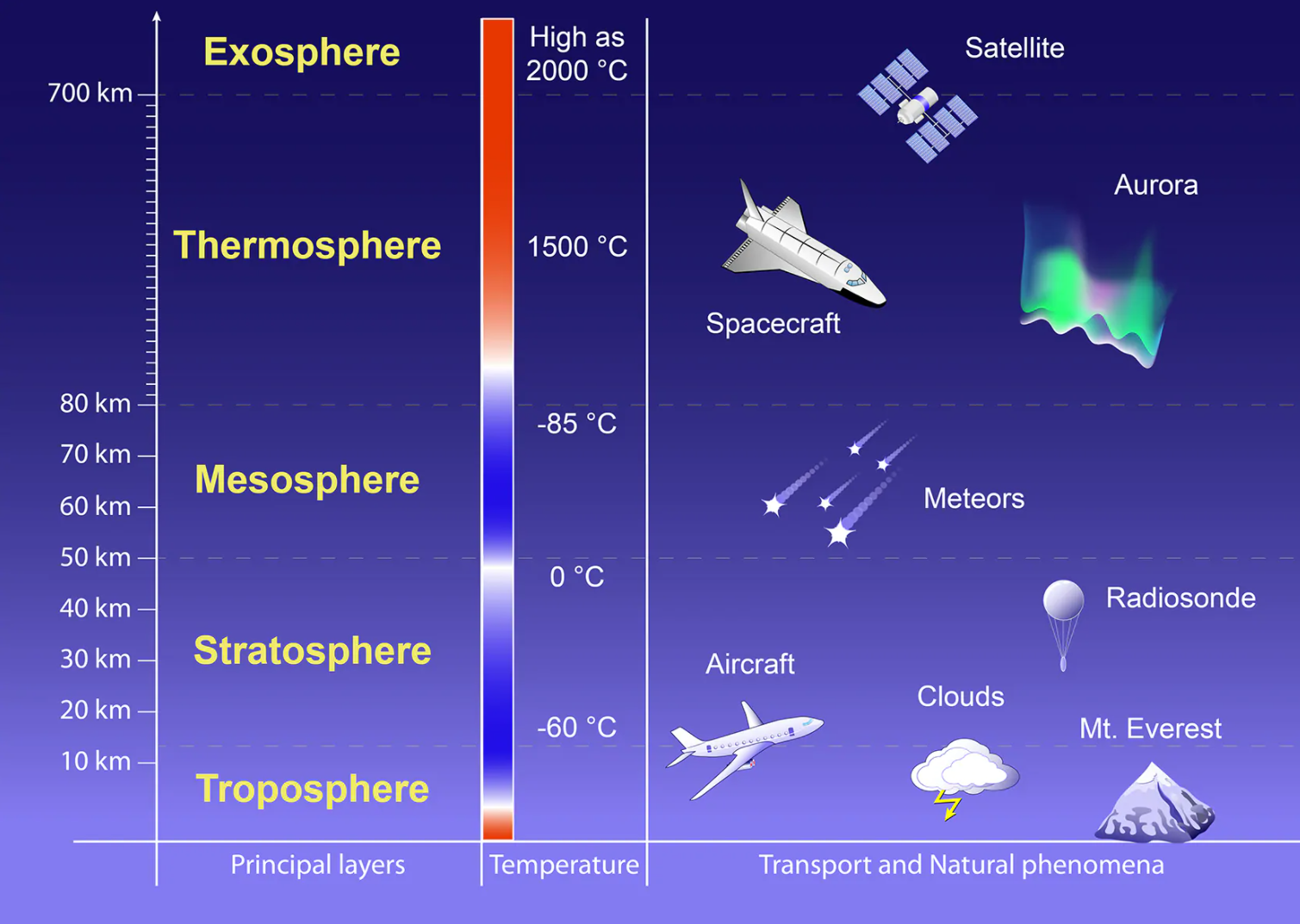

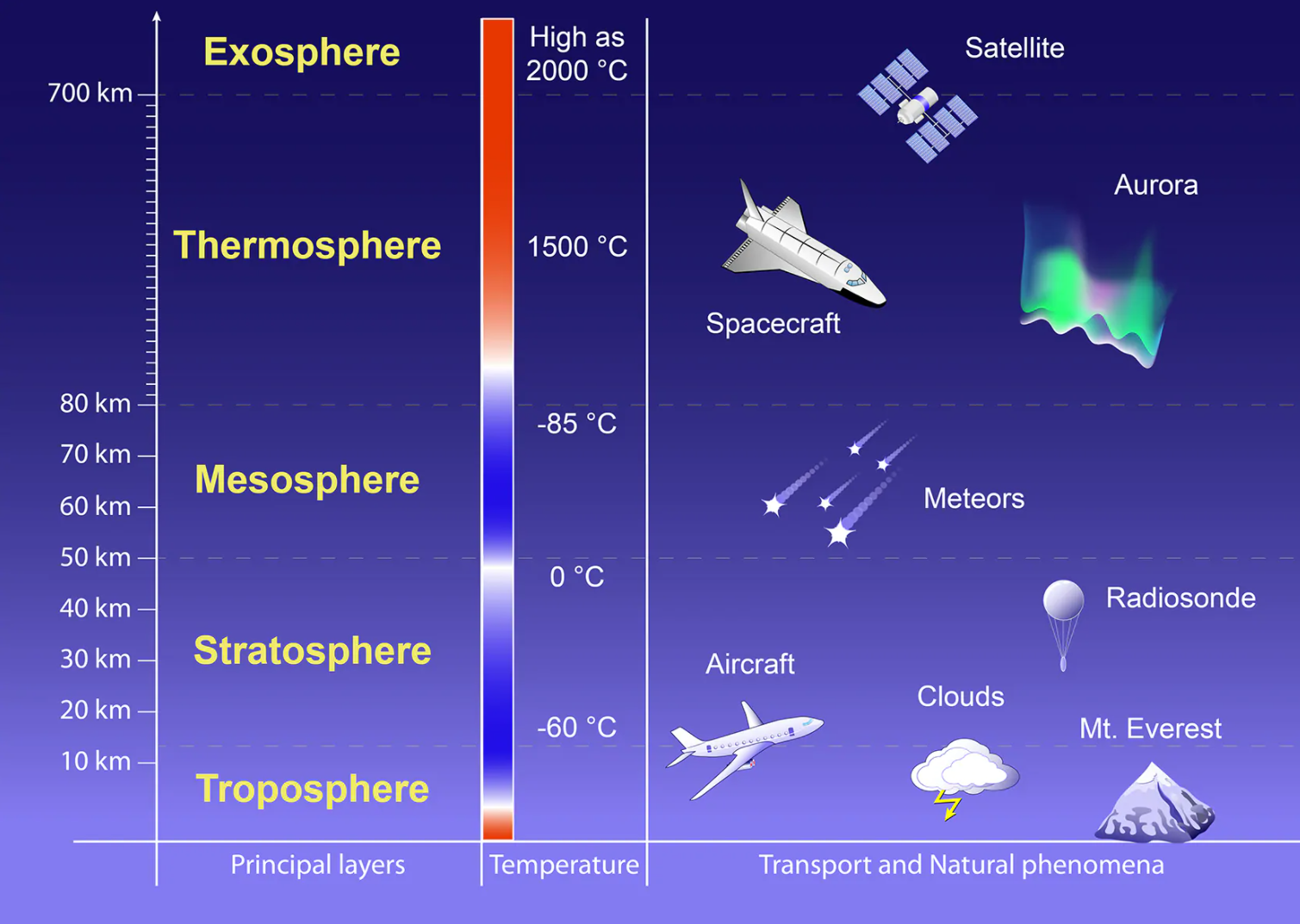

Nella immagine gli strati dell’atmosfera terrestre secondo la scienza moderna. Come facevano gli antichi a conoscere dell’esistenza della mesosfera e della termosfera?

Nella foto successiva la sottile fascia atmosferica fotografata dall’altezza di 35 km da un pallone sonda.

Facciamo un breve cenno alla coenatio rotunda di Nerone in cui le stelle giravano continuamente attorno a lui, per come scriveva Svetonio.

E’ evidente la similitudine con il temporalmente precedente Pantheon simile al cielo a testimonianza dell’origine augustea e non adrianea della concezione della struttura.

Nella foto resti della presunta coenatio rotunda di Nerone.

Di seguito una moneta che dovrebbe ritrarre la coenatio su cui è scritto: mac (machina) aug (augusta). Qualcuno sostiene che ruotasse il pavimento, ma nella visione dell’epoca la terra era stazionaria.

Ora trattiamo del punto fondamentale della nostra ricerca: la musica per l’ascesa agli astri studiata dai pitagorici è stata usata anche nel Pantheon?

Da dottrina pitagorica, i riti per l’ascesa astrale dell’anima venivano effettuati con vocalizzazioni, toni e semitoni corrispondenti ad astri e muse.

Lo gnostico Marco così riproduceva in questo schema la corrispondenza di vocali, astri, intonazioni, note musicali e muse.

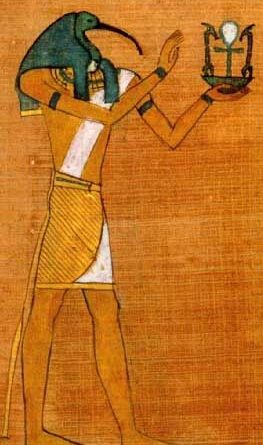

Circa l’ascesa tramite la musica: si vedano le canne della siringa di Pan che rappresentano gli astri.

In un altra foto una statua di siringa (con le canne astrali) e Pan.

Vediamo poi l’ipogeo di Santa Maria in Stelle, presso Verona. Nessuno ha ancora capito che quei strani tubi sono in realtà le canne cosmiche della siringa di pan quale rappresentazione dell’armonia musicale delle sfere.

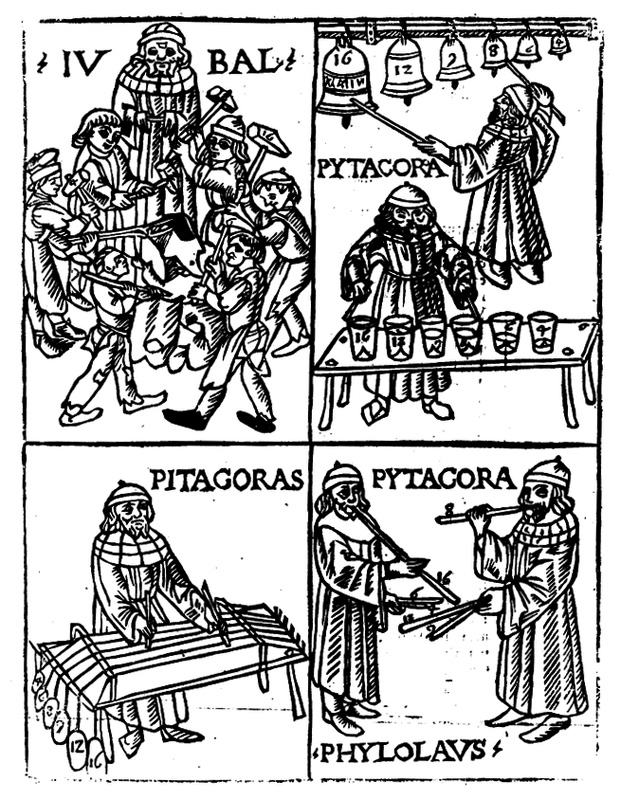

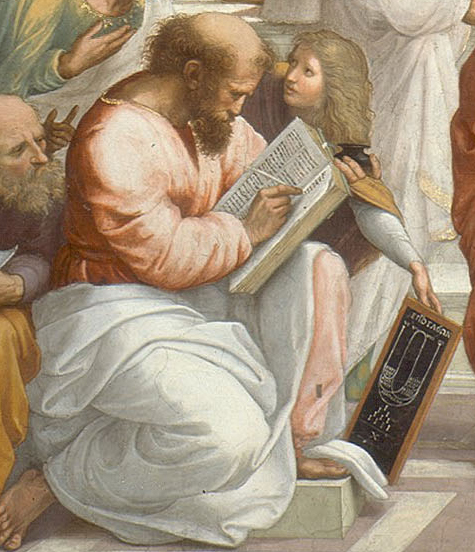

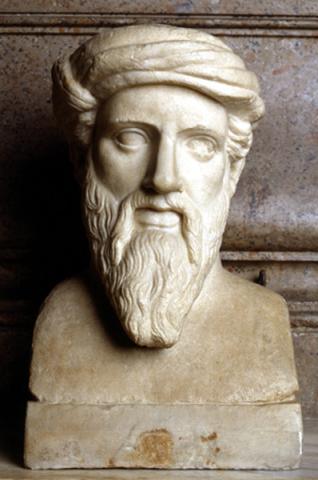

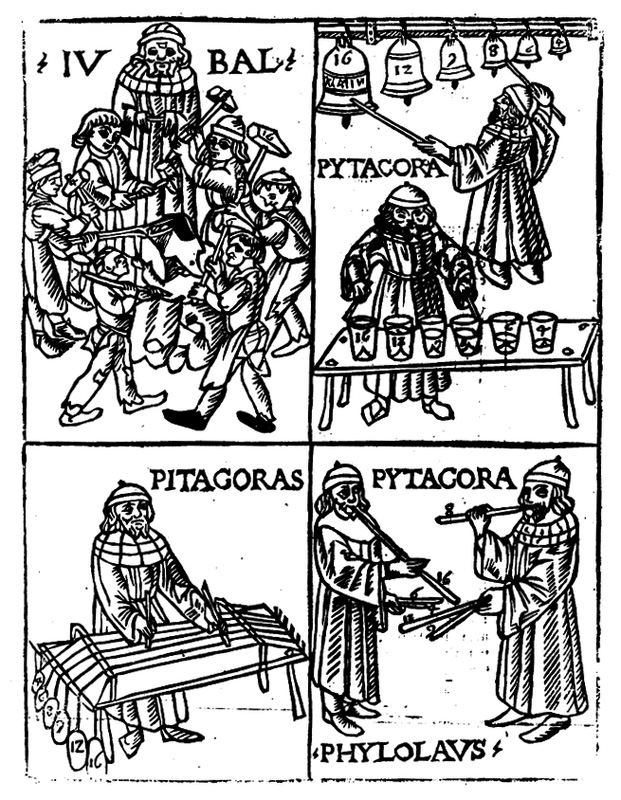

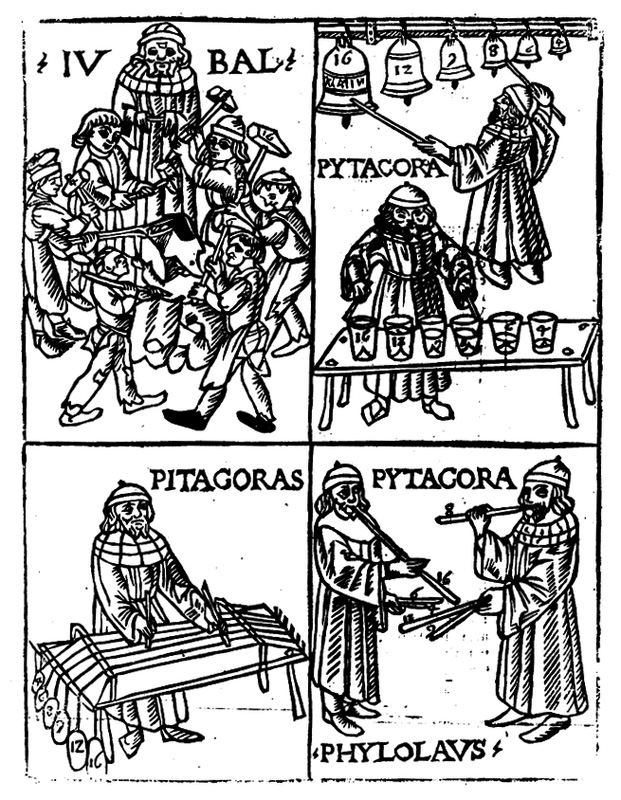

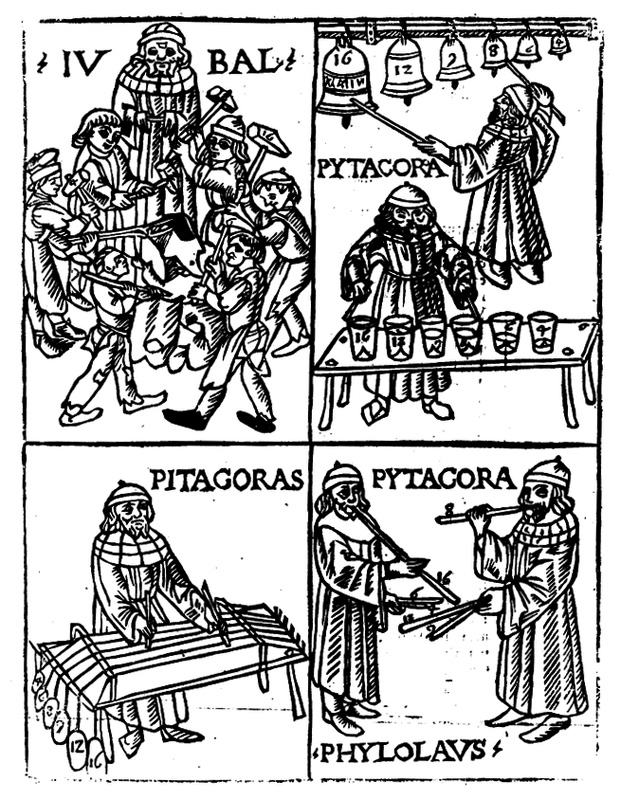

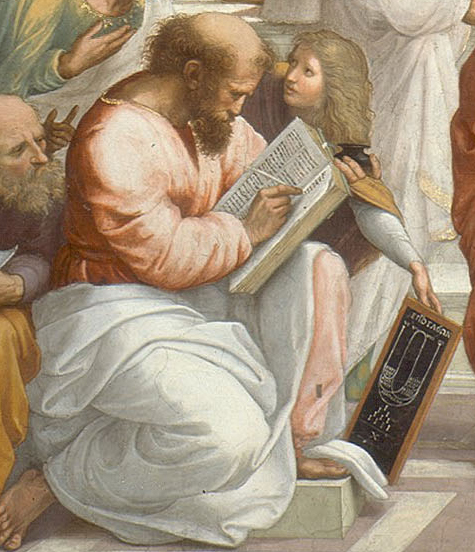

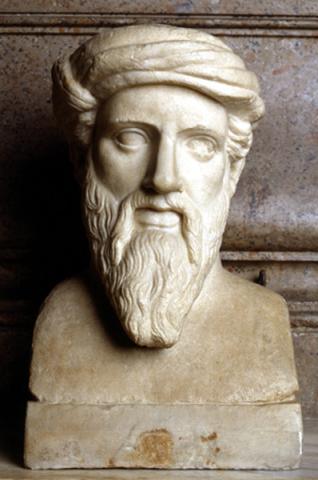

Un altra immagine ritrae Pitagora che studia l’armonia e la ratio con diversi strumenti musicali.

Da Zeugma (in Turchia) viene questo bel mosaico delle muse.

Quì abbiamo un askos pitagorico a forma di sirena. la siringa a sette canne rappresenta l’armonia dei sette astri, la melagrana il ciclo vita morte. Nel manico è raffigurata l’anima del defunto gestita dalla sirena del mito di ER con in mano la siringa.

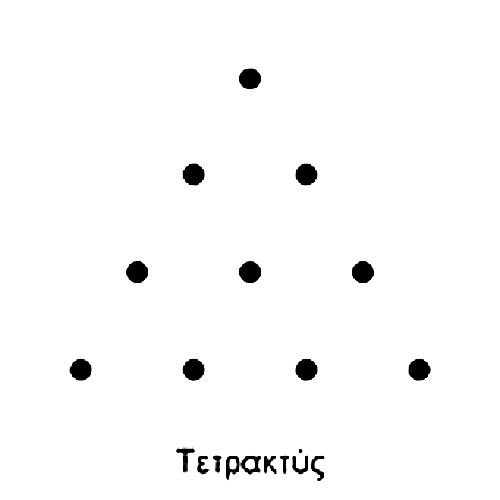

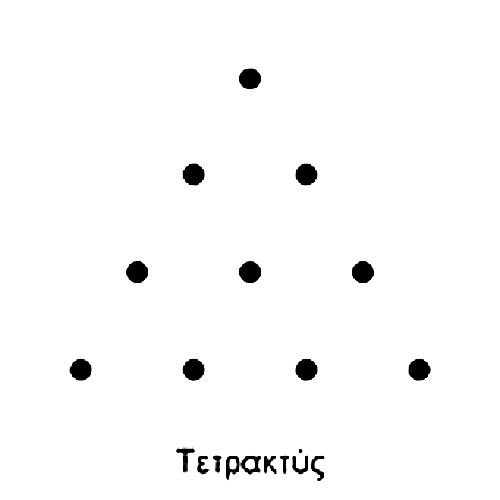

Nella successiva immagine vediamo la tetraktys, armonia delle sirene, che raffigura l’universo musicale pitagorico: l’ottava (1 in rapporto a 2), la quinta (2 in rapporto 3) e la quarta (3 in rapporto a 4).

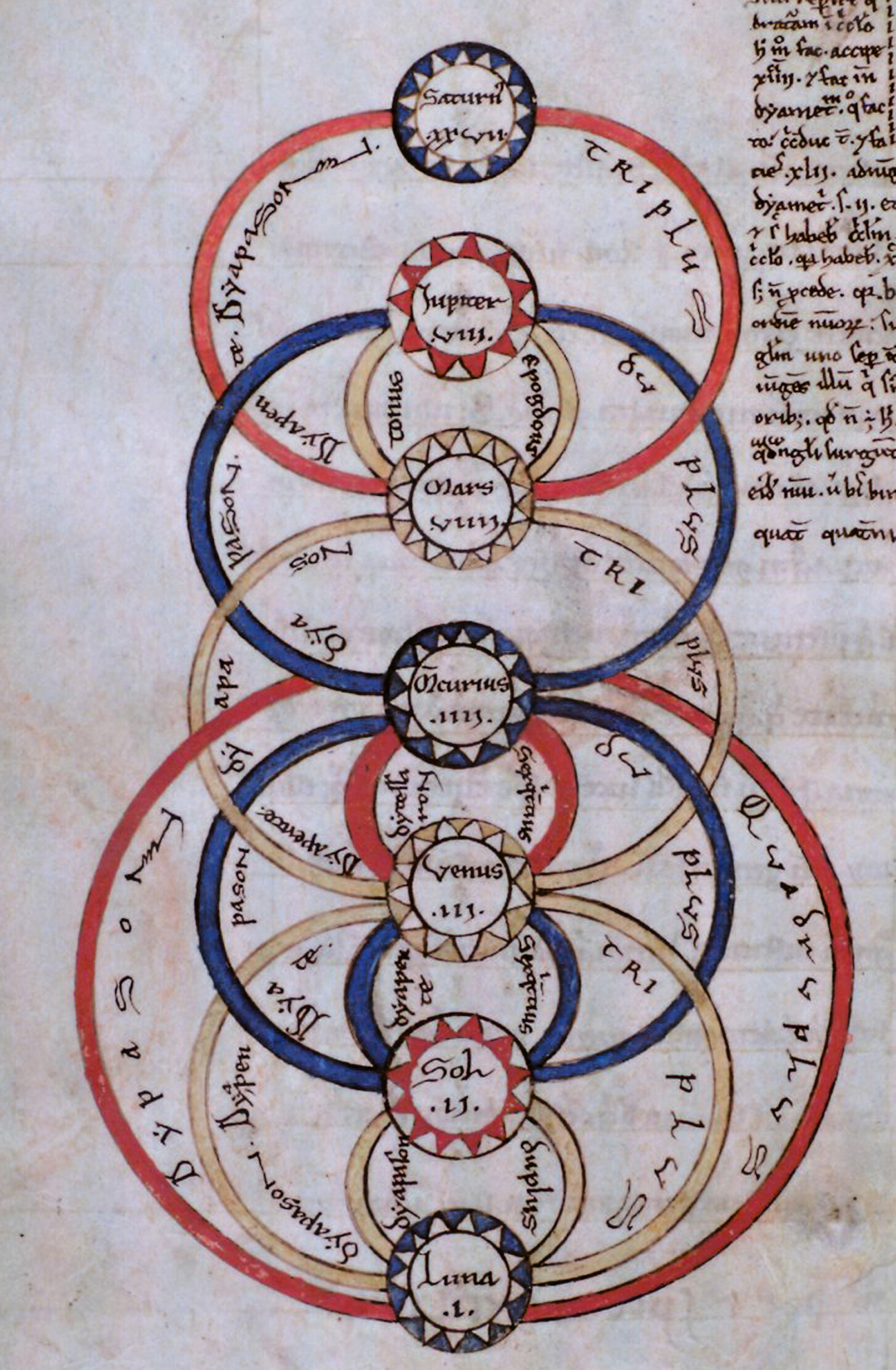

Nel sistema dei diapason pitagorici e nel Timeo di Platone, il diapason della luna risuona doppio fino al sole, triplo fino a venere e quadruplo fino a mercurio, eccetera.

Dal museo di Capua vediamo un mosaico con coro sacro del terzo secolo dopo cristo, mentre dalla Villa del Cicerone di Pompei il mosaico di un musicista con timpano.

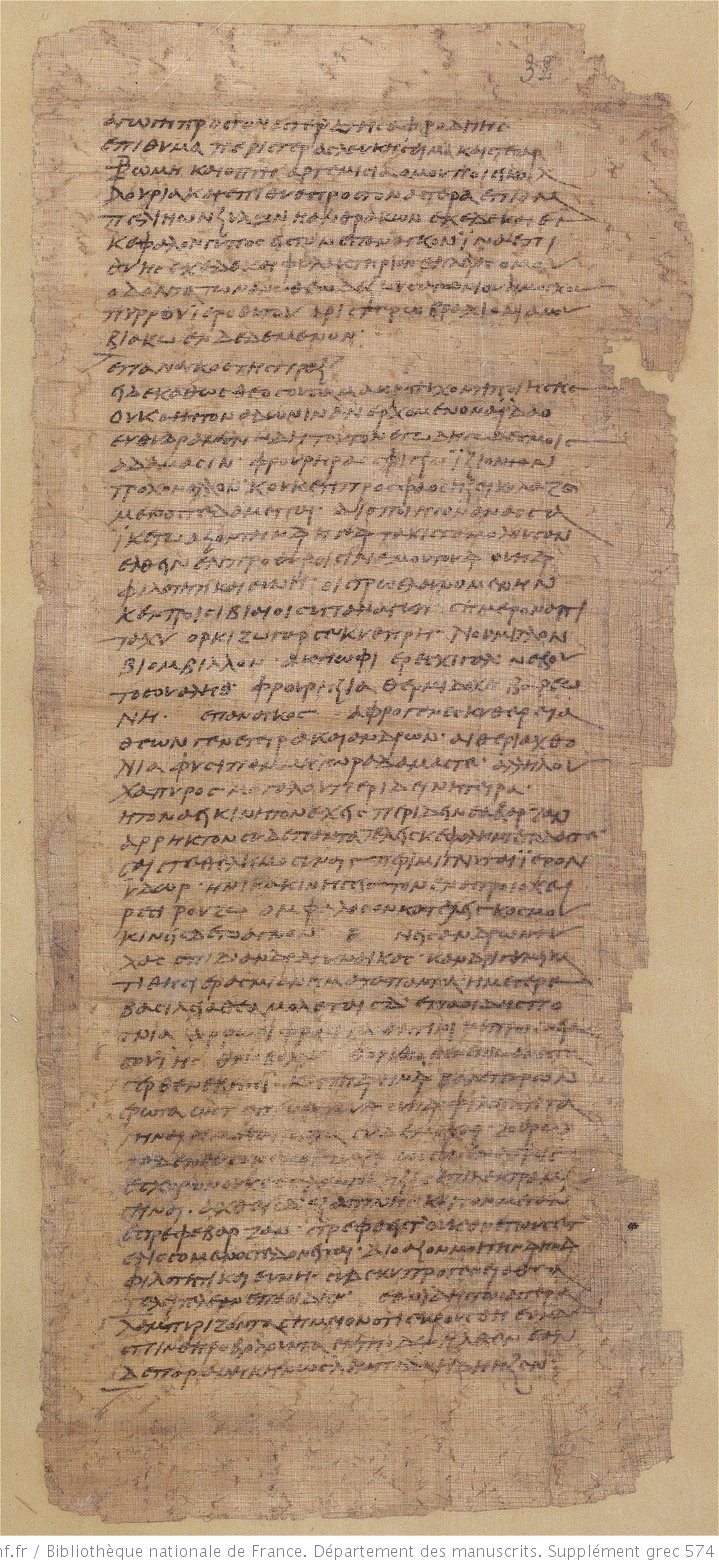

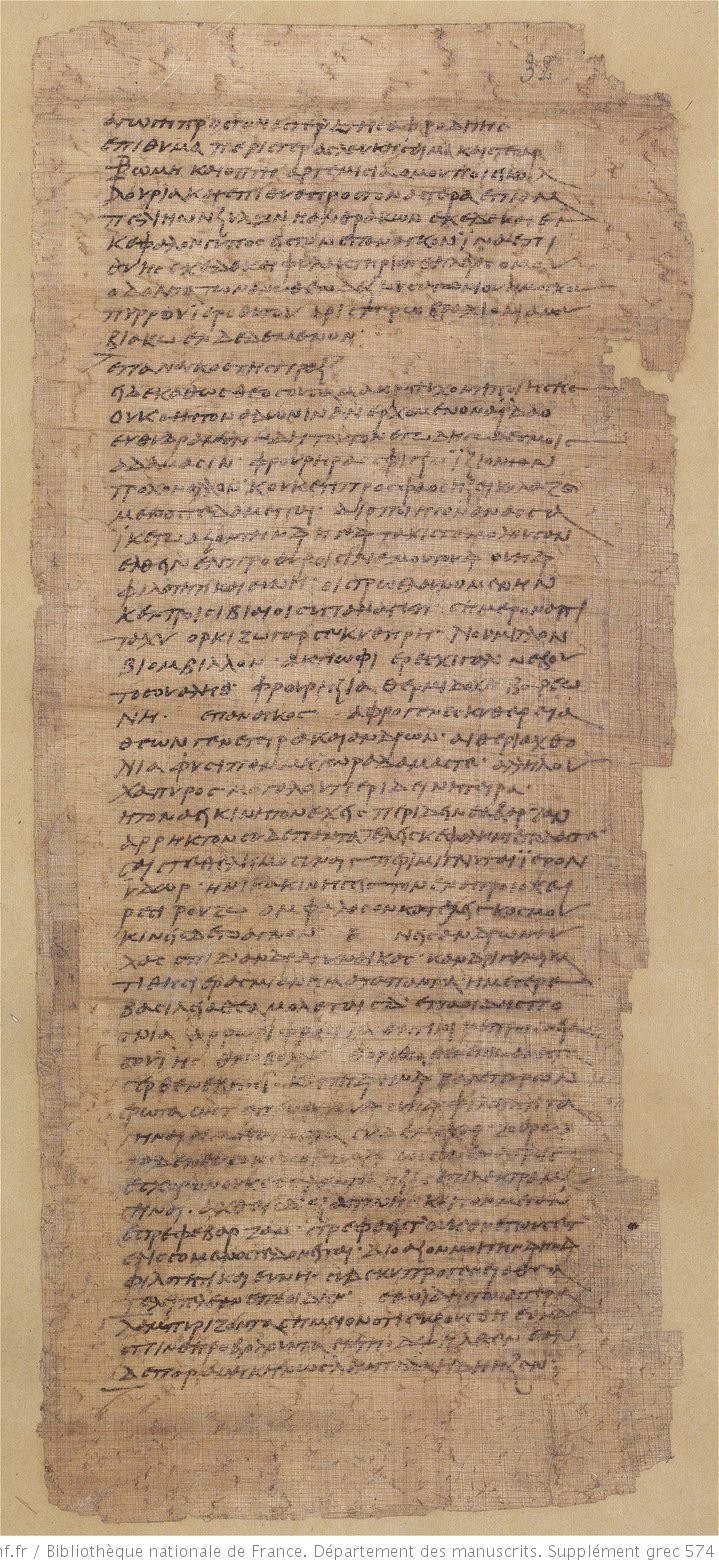

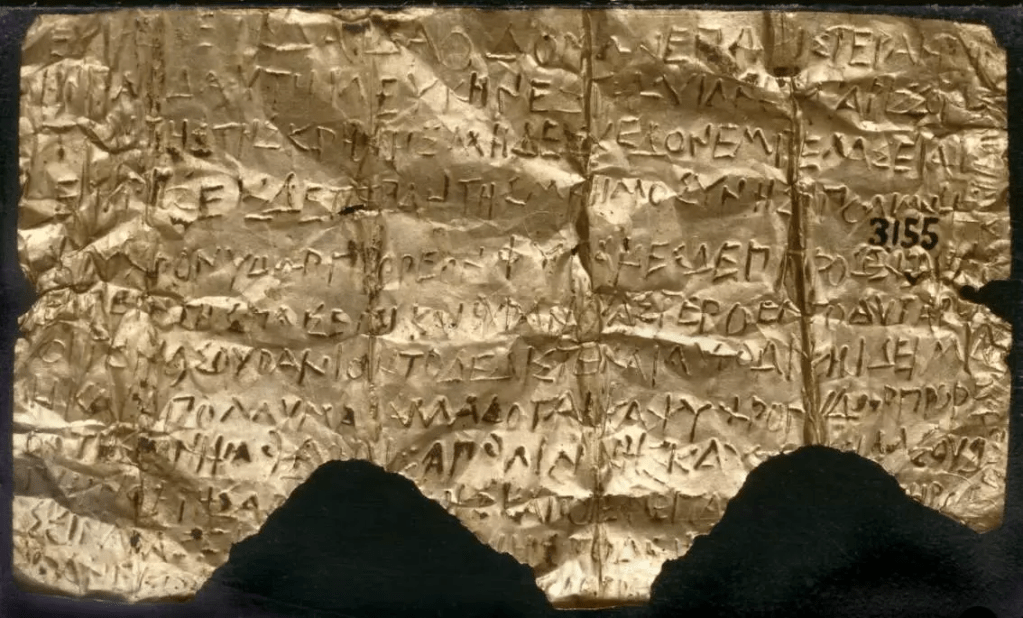

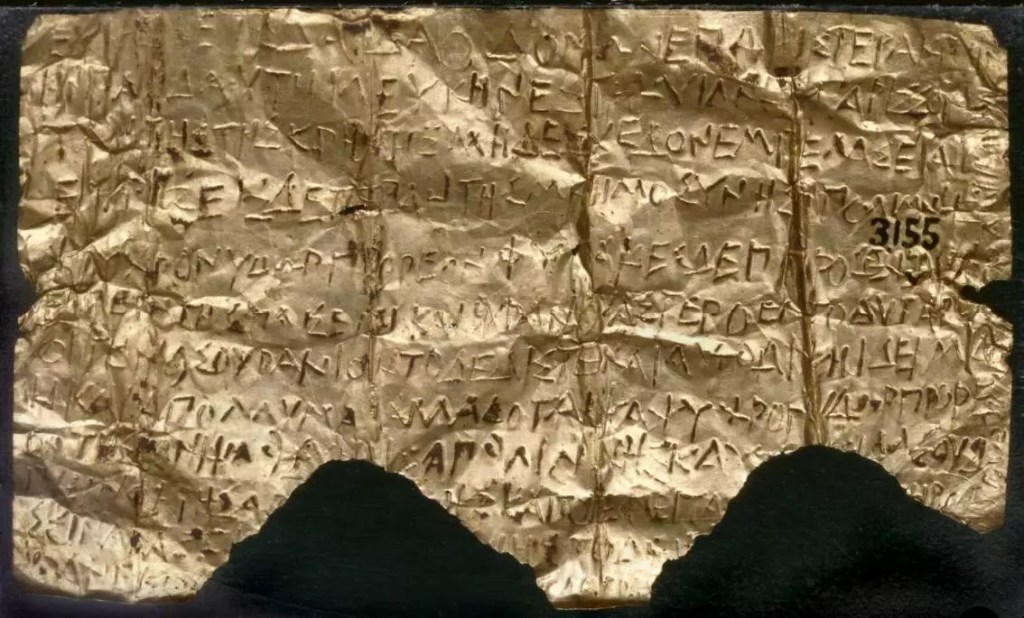

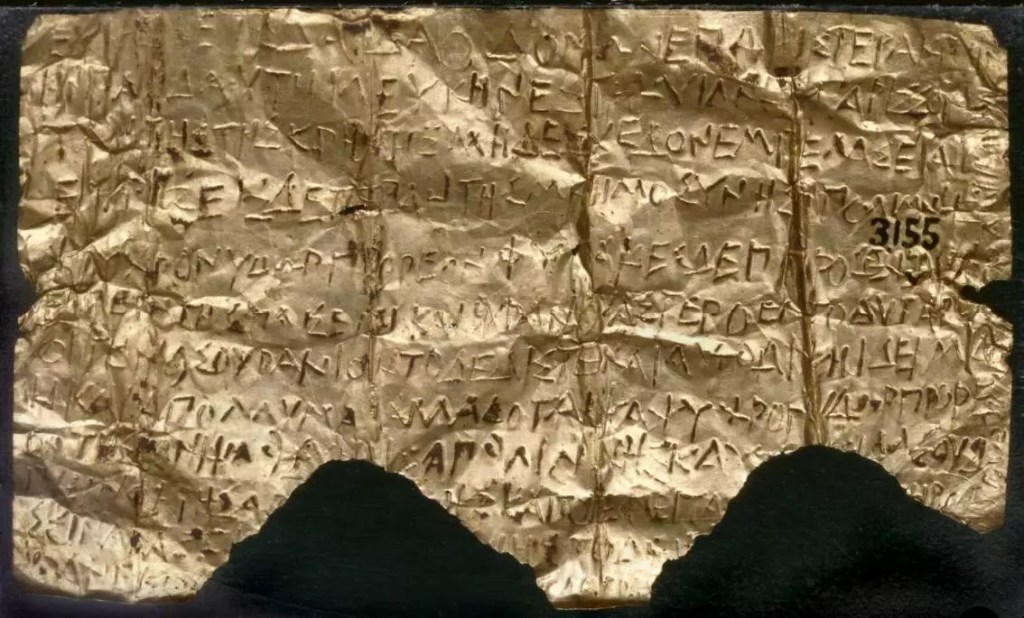

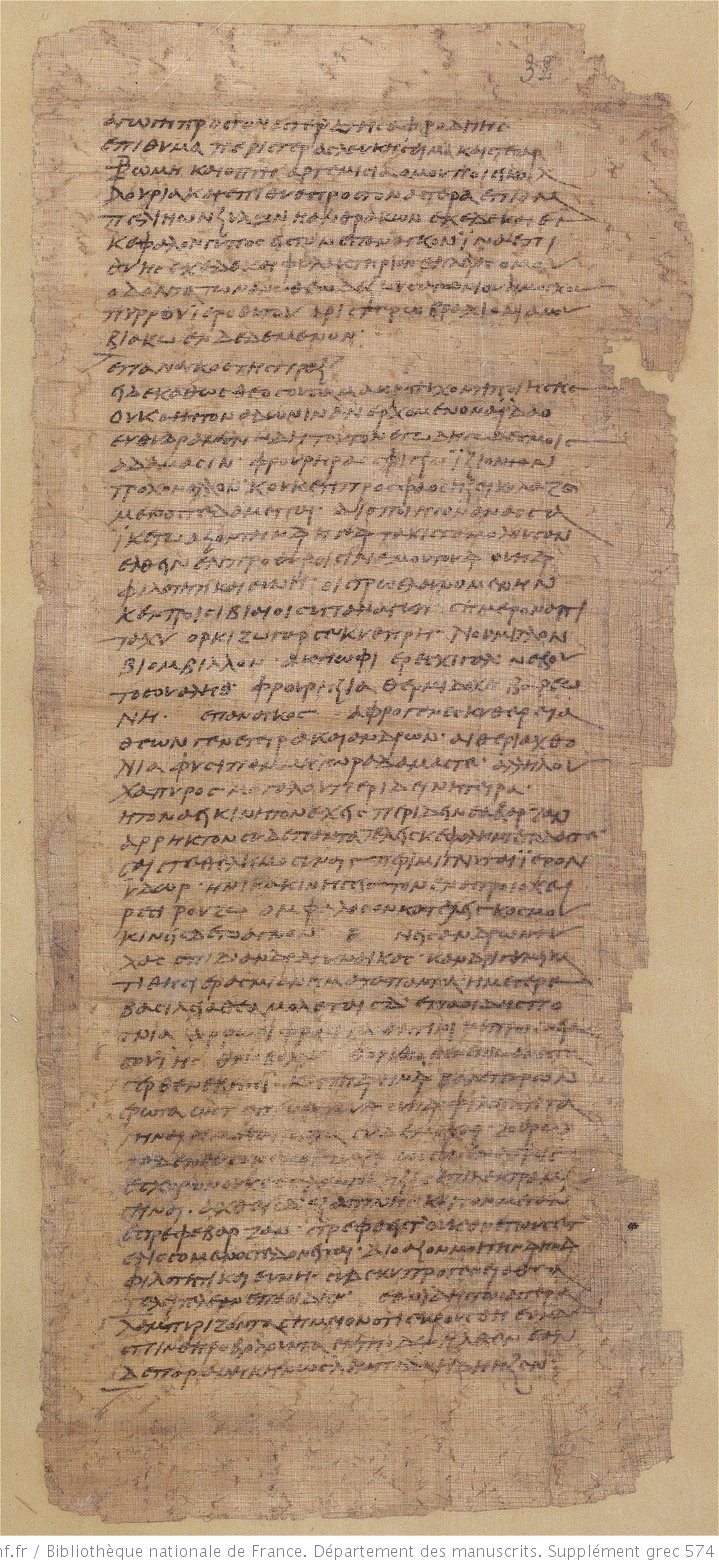

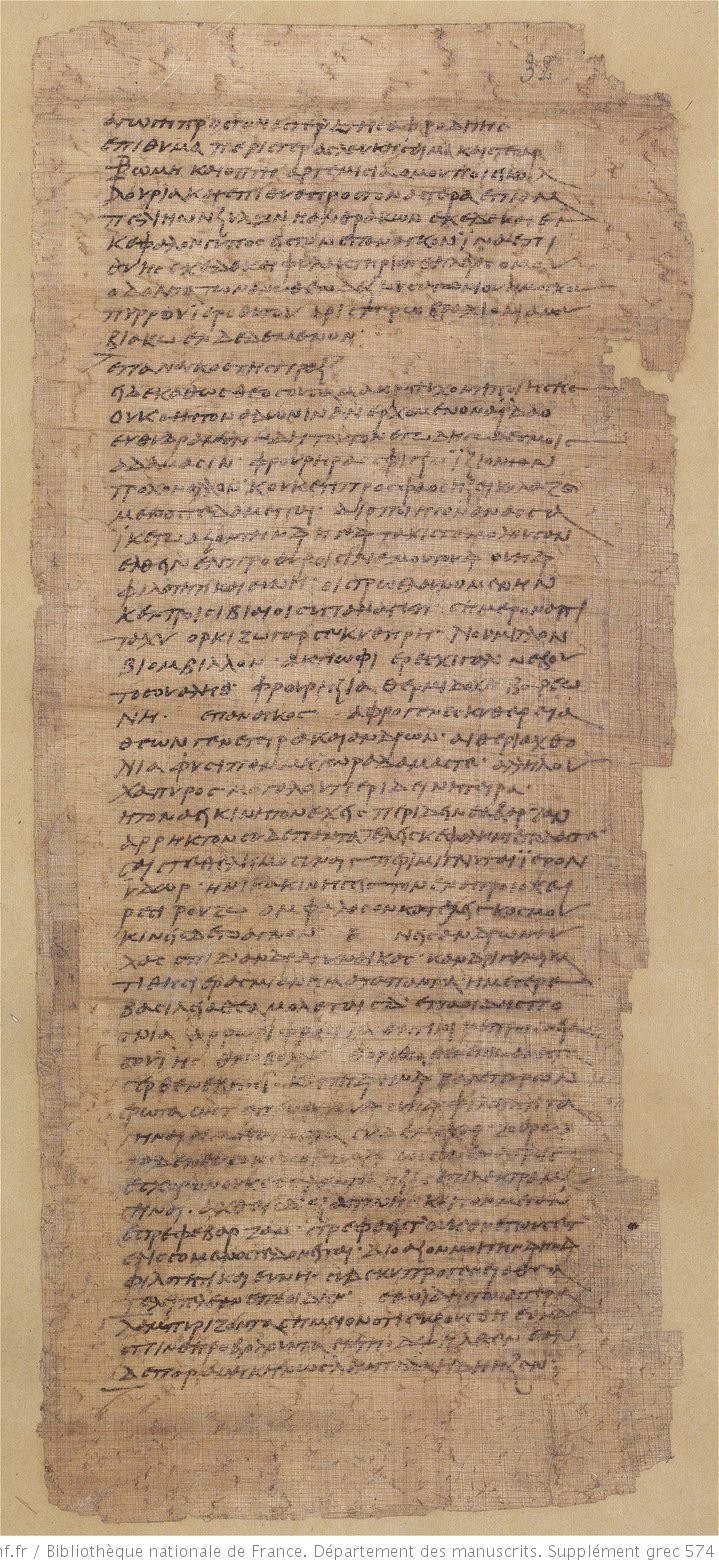

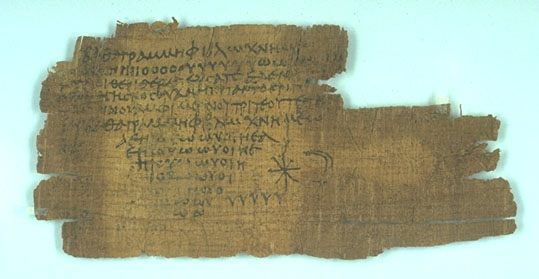

Nel Grande Papiro Magico di Parigi chiamato anche apathanatismos (ricetta di immortalità) e in altri papiri simili sono presenti intonazioni con vocali, fatte durante i logoi (parole di passo) corrispondenti a ciascun astro, durante il rito che mirava a pulire, lustrare, l’anima per l’ascesa agli astri, ovvero per l’immortalità.

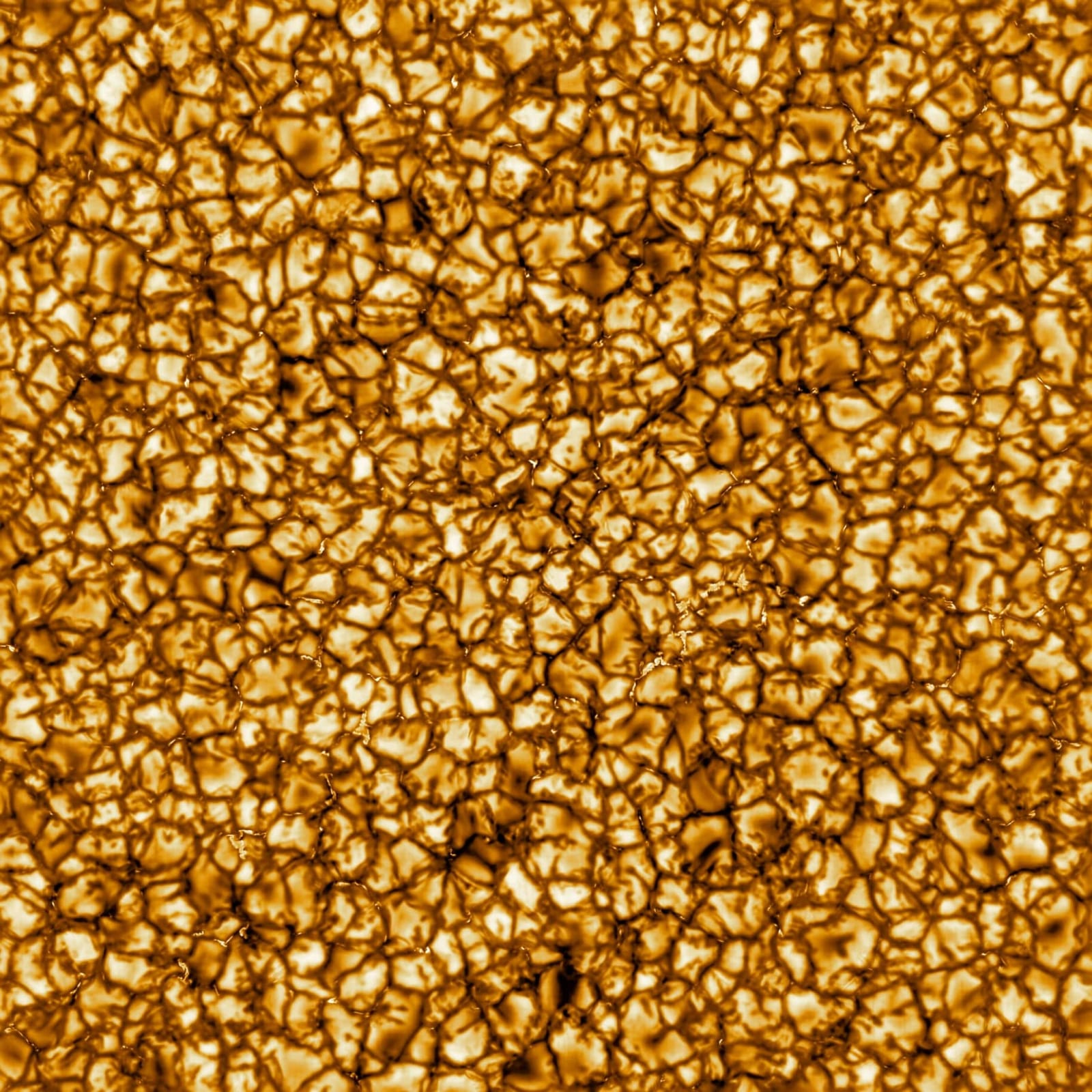

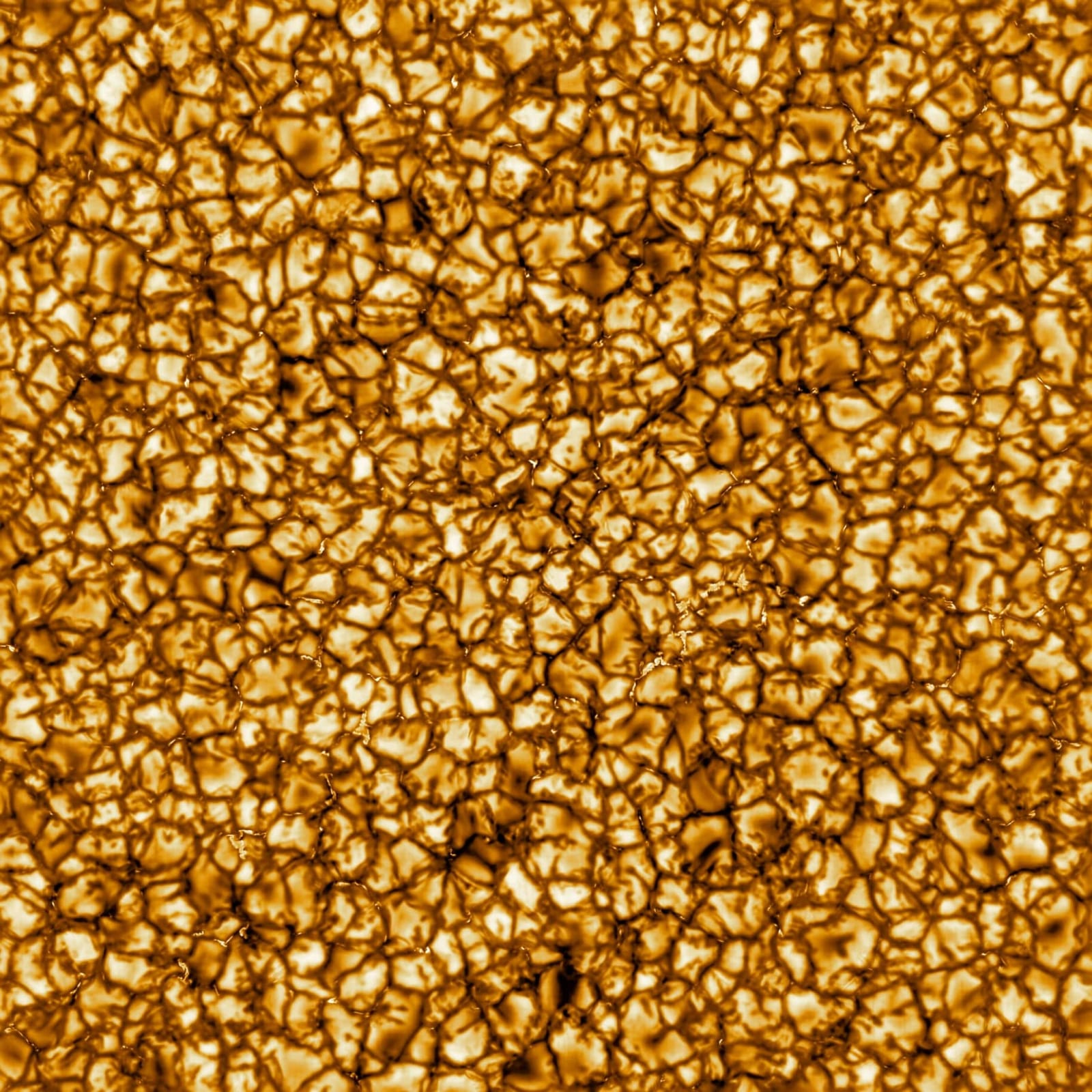

Qui una foto del papiro magico di Parigi e accanto una foto della struttura alveolare (oro?) del Sole fatta dall’osservatorio di Mauna Kea nelle Isole Hawaii.

Considerato che, nel rito, il logos del Sole viene subito dopo quello della Luna non vi sono, secondo noi, dubbi sull’attribuzione all’epoca ellenistico-alessandrina del papiro e non alla cultura mitraica, molto più tarda.

Ne consegue che il papiro magico per l’immortalità potrebbe essere stato verosimilmente usato dall’imperatore nei riti per la sua immortalità tramite ascesa agli astri.

Trattiamo ora della forma del cielo e delle similitudini col Pantheon.

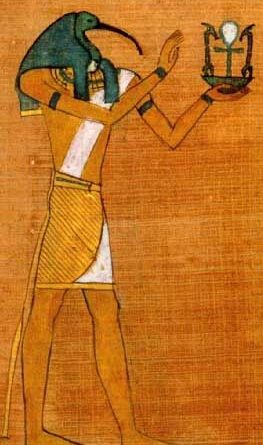

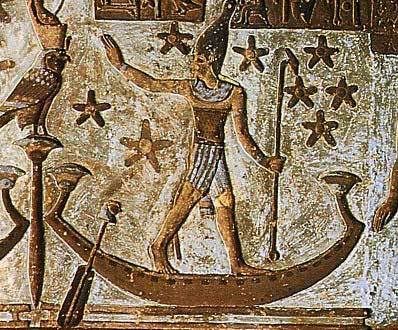

In questa stele egizia vediamo la dea Nut, con il corpo blu arcuato a cilindro, che sta a simboleggiare il firmamento. Qualche coincidenza con la struttura cilindrica originaria del Pantheon? Ovvero vi sono richiami egiziani, non solo nei riti ermetici, ma anche nella struttura?

Questo papiro raffigura un‘altra immagine della dea Nut arcuata sopra la terra, il dio Geb (Gaia) sdraiato. A metà sta il dio Shu che rappresenta l’aria.

Qui vediamo una rappresentazione biblica del firmamento (raqia in ebraico) anch’esso arcuato a cilindro.

Se ne ricava che la strana forma del tempio del Pantheon, uguale al cilindro del cielo di cui parlava Ermete Trismegisto, sarebbe stata influenzata dalle concezioni cosmologiche egizie.

Oltre al richiamo alla cosmologia egizia, uno dei motivi della forma cilindrica era, secondo noi, l’uso rituale della struttura da usare per lustrazioni circumambulatorie.

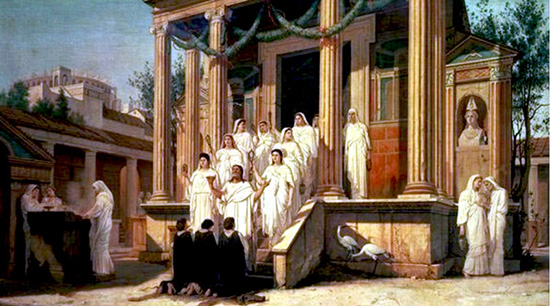

Crediamo che i riti lustrali circumambulatori, che riteniamo fossero tenuti all’interno per la purificazione dell’anima dell’imperatore, fossero svolti in direzione uguale al moto stellare, ovvero in senso orario (strofa).

Supponiamo, poi che nel Mausoleo funebre di Augusto fossero tenuti riti circumambulatori in direzione contraria al moto stellare, ovvero in senso anti-orario (antistrofa).

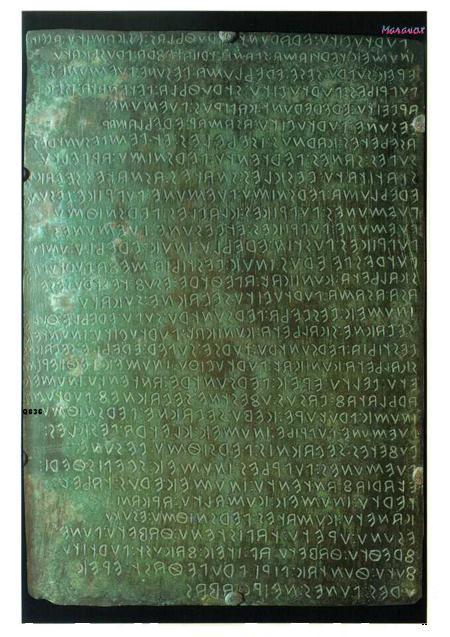

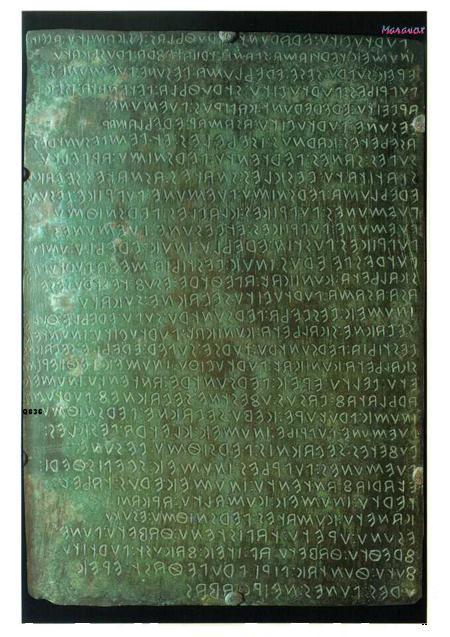

Nella foto le tabulae iguvinae : esse cono sette tavole bronzee rinvenute nell’antica Ikuvium (Gubbio). In esse sono descritti i cerimoniali di lustratio.

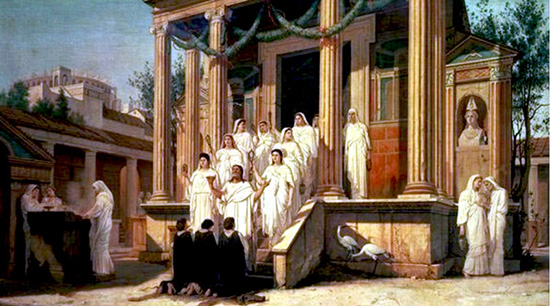

Sopra ammiriamo una processione imperiale ritratta nell’Ara Pacis di Roma.

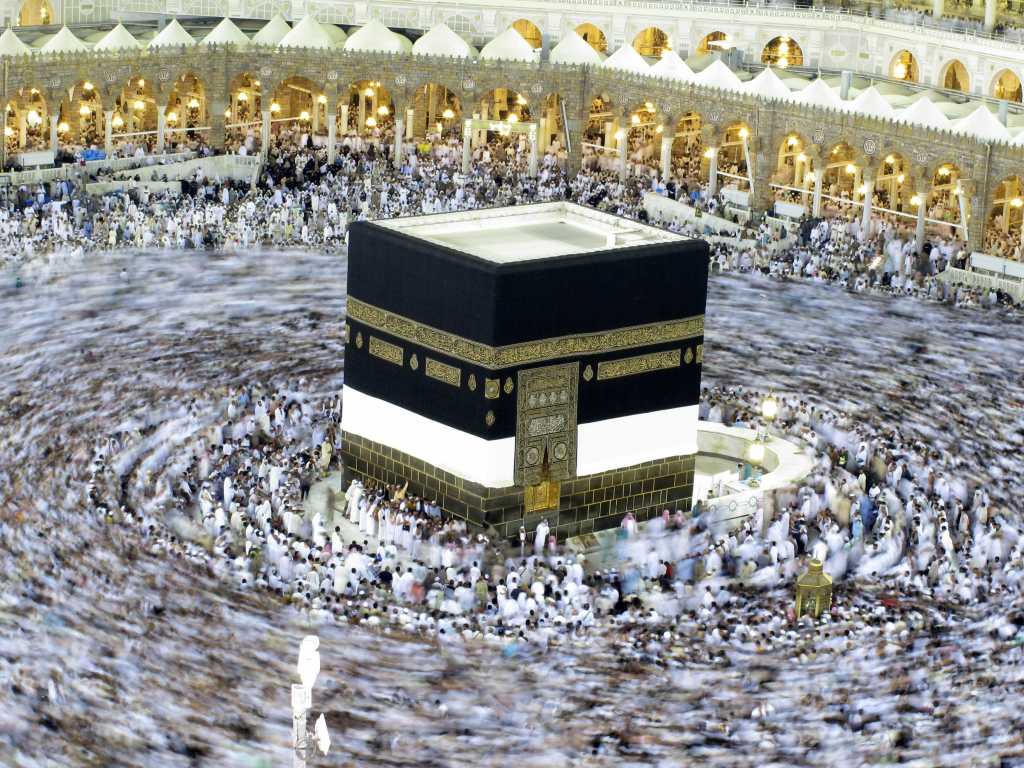

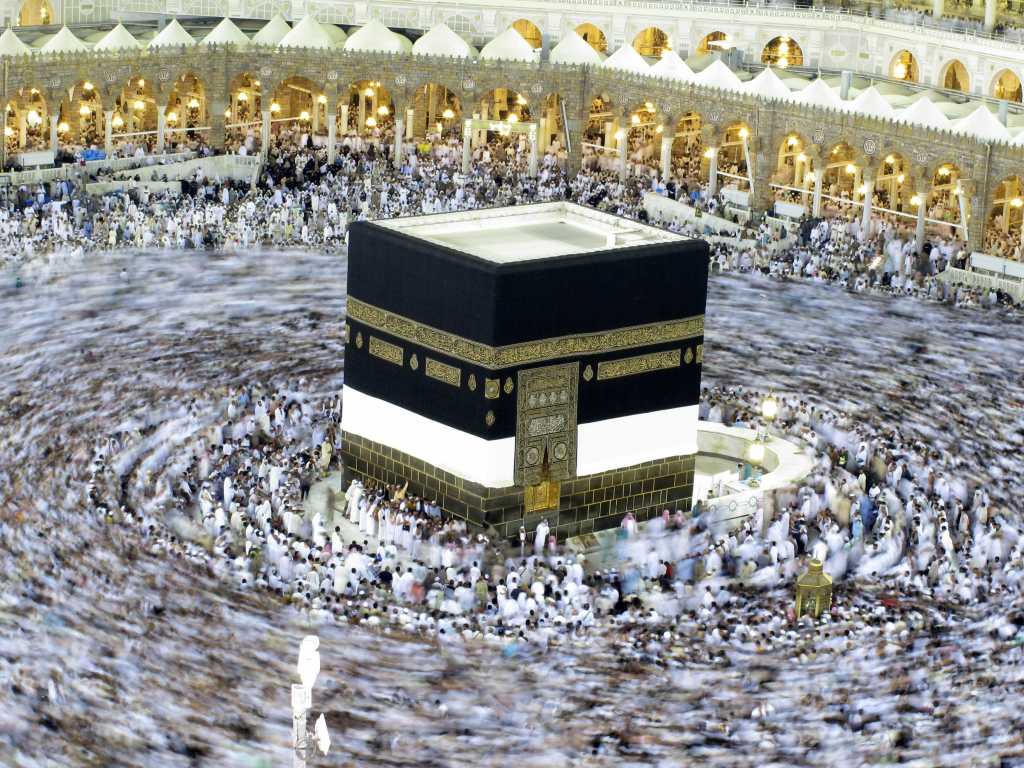

Una circumambulazione in senso antiorario è quella che si svolge oggi attorno alla Kaba, a La Mecca, in Arabia Saudita: ovvero il rito del ṭawaf.

Nella foto danze circumambulatorie odierne celebrate in Svezia attorno al midsommarstong, circumambulazione in senso orario attorno al palo, qui aggiunto di simbologie moderne.

Circa i concetti di strofa e antistrofa trattiamo ora delle danze dei pianeti e dei labirinti lustrali.

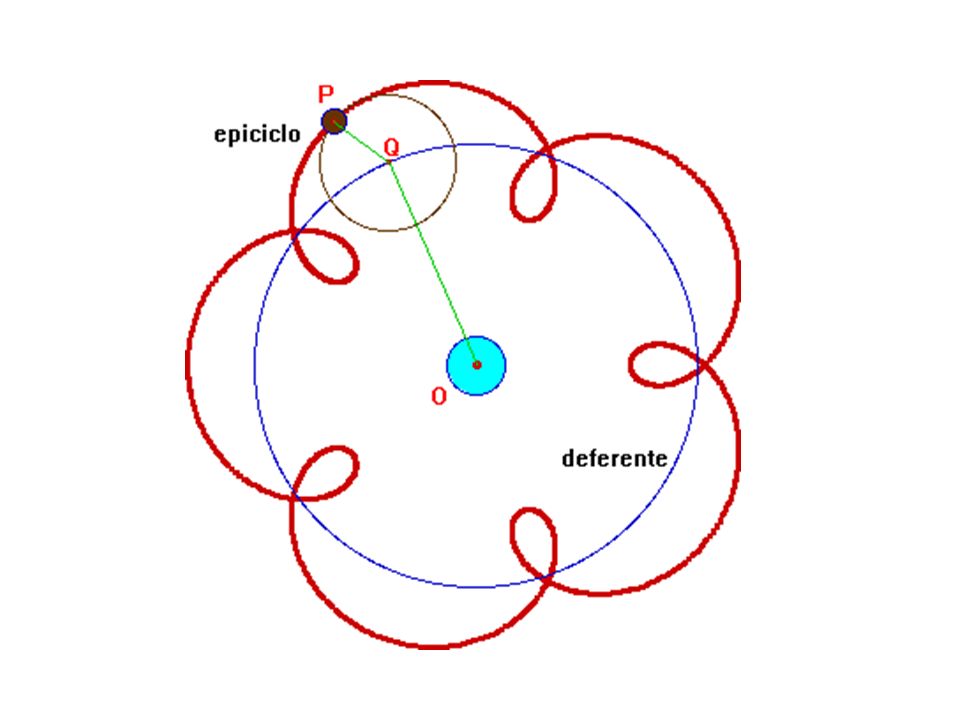

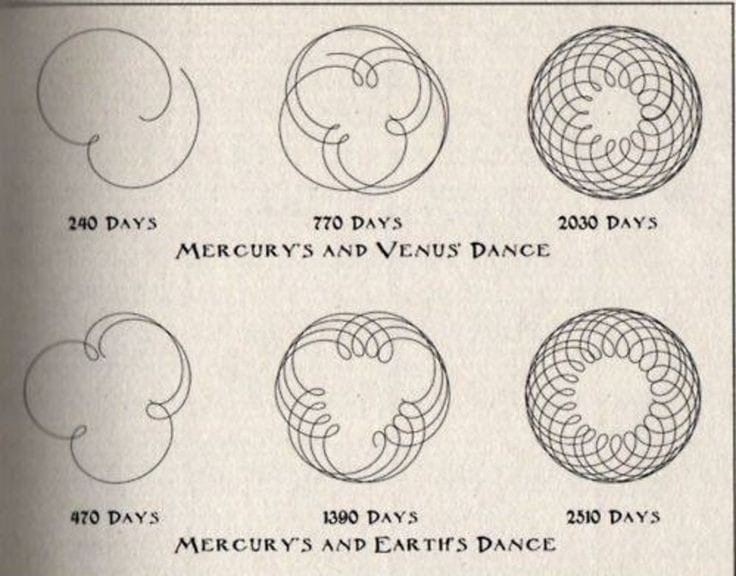

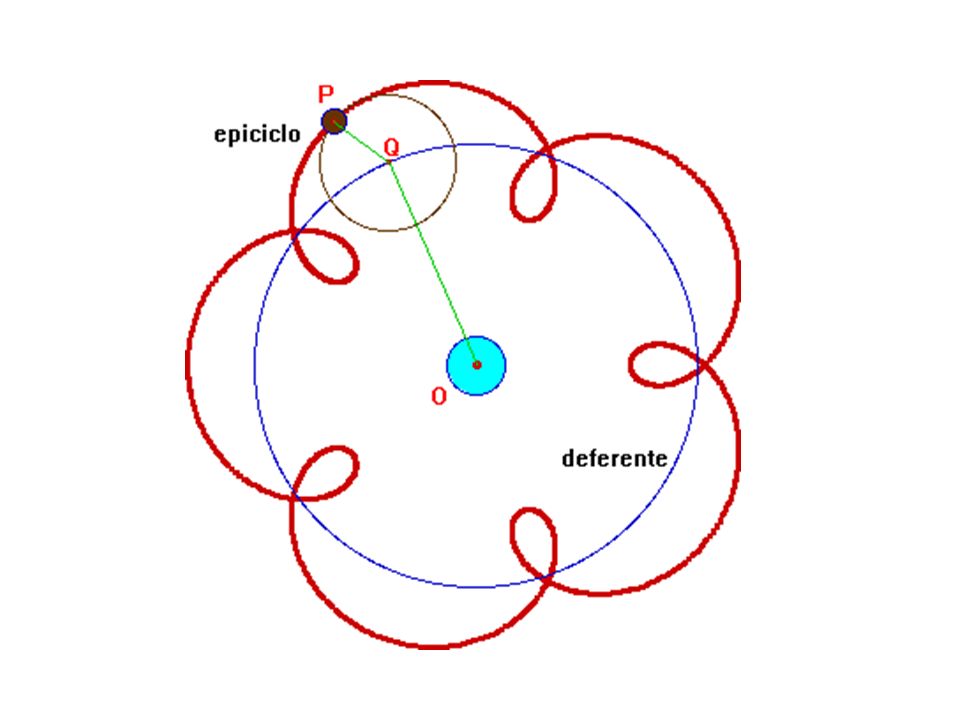

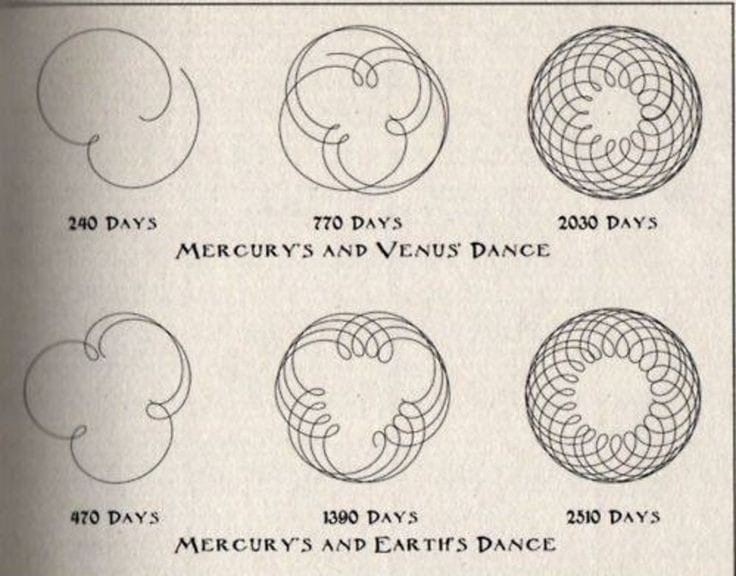

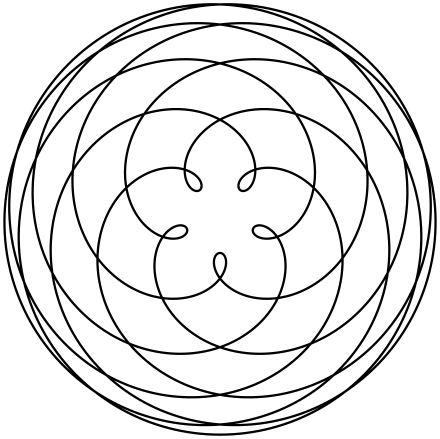

Di seguito una rappresentazione tolemaica della scoperta pitagorica del moto retrogrado. Esso sarebbe stato causato dalla combinazione di due orbite circolari (epiciclo e deferente).

Nell’immagine moti retrogradi di Marte (in rosso), Mercurio (in viola) e Venere (in verde) visti dalla Terra (tempo di percorrenza sette anni). E’ da notare che a ogni nodo corrisponde un moto retrogrado

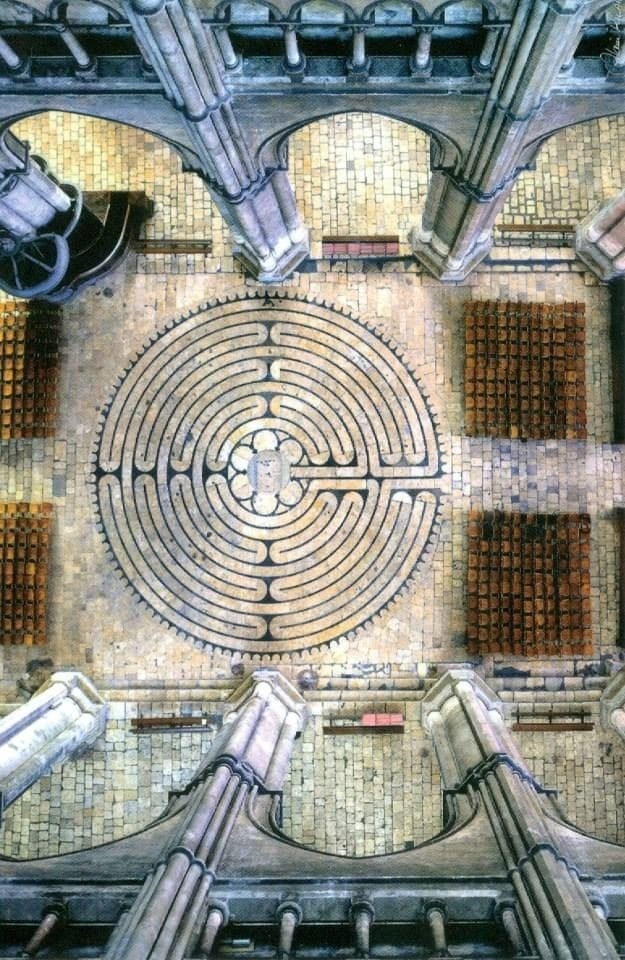

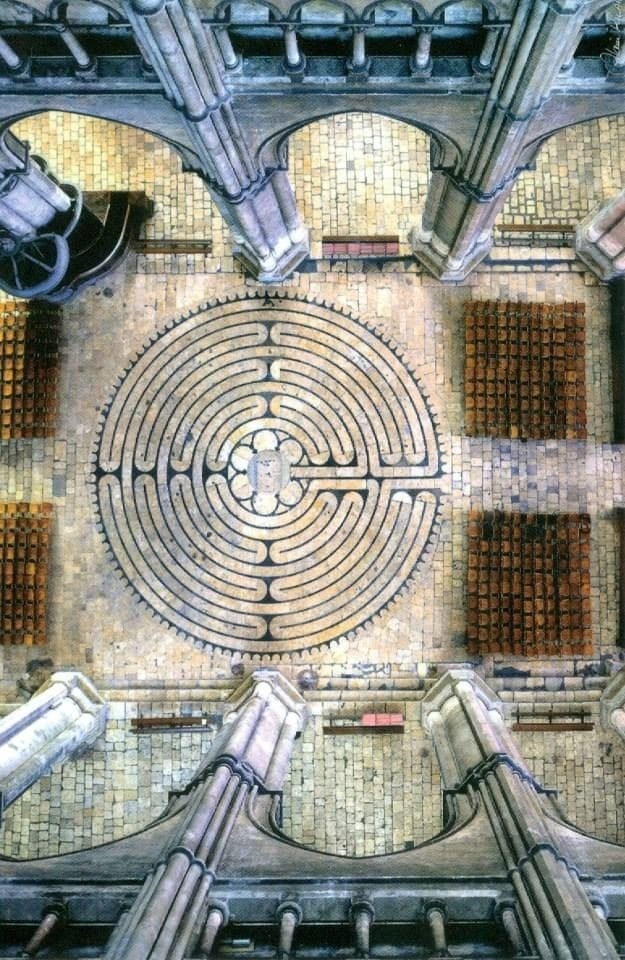

Riteniamo che nel labirinto (nella foto Teseo e Minotauro a Paphos, Cipro), imitando il moto dei pianeti, si praticassero cerimonie lustrali in strofa (avanti) e antistrofa (indietro). Qui il labirinto della la cattedrale di Chartres: notare la rosa interna.

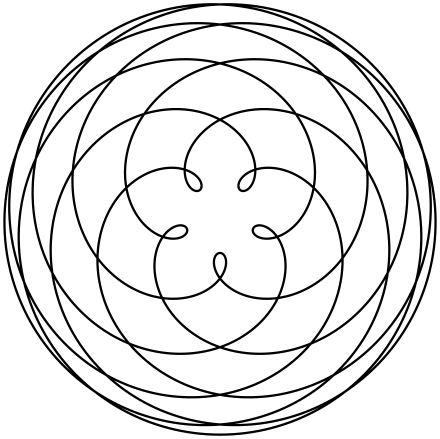

Nella foto la danza dei pianeti Mercurio e Venere negli anni. La danza di Mercurio assume la forma di una corona circolare. Il pianeta Venere assume la forma di una rosa cosmica (pentalfa) con i suoi moti retrogradi in otto anni.

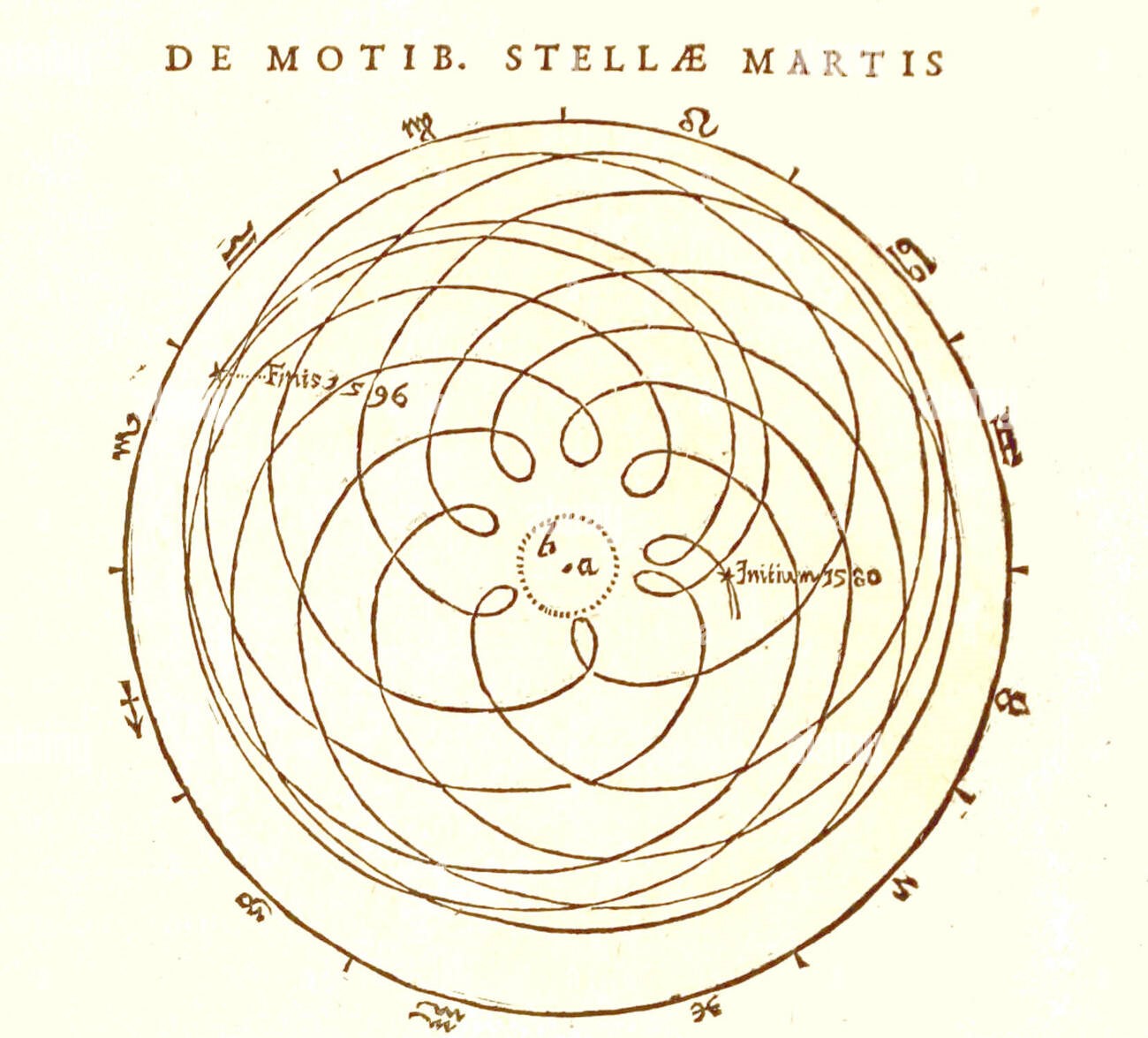

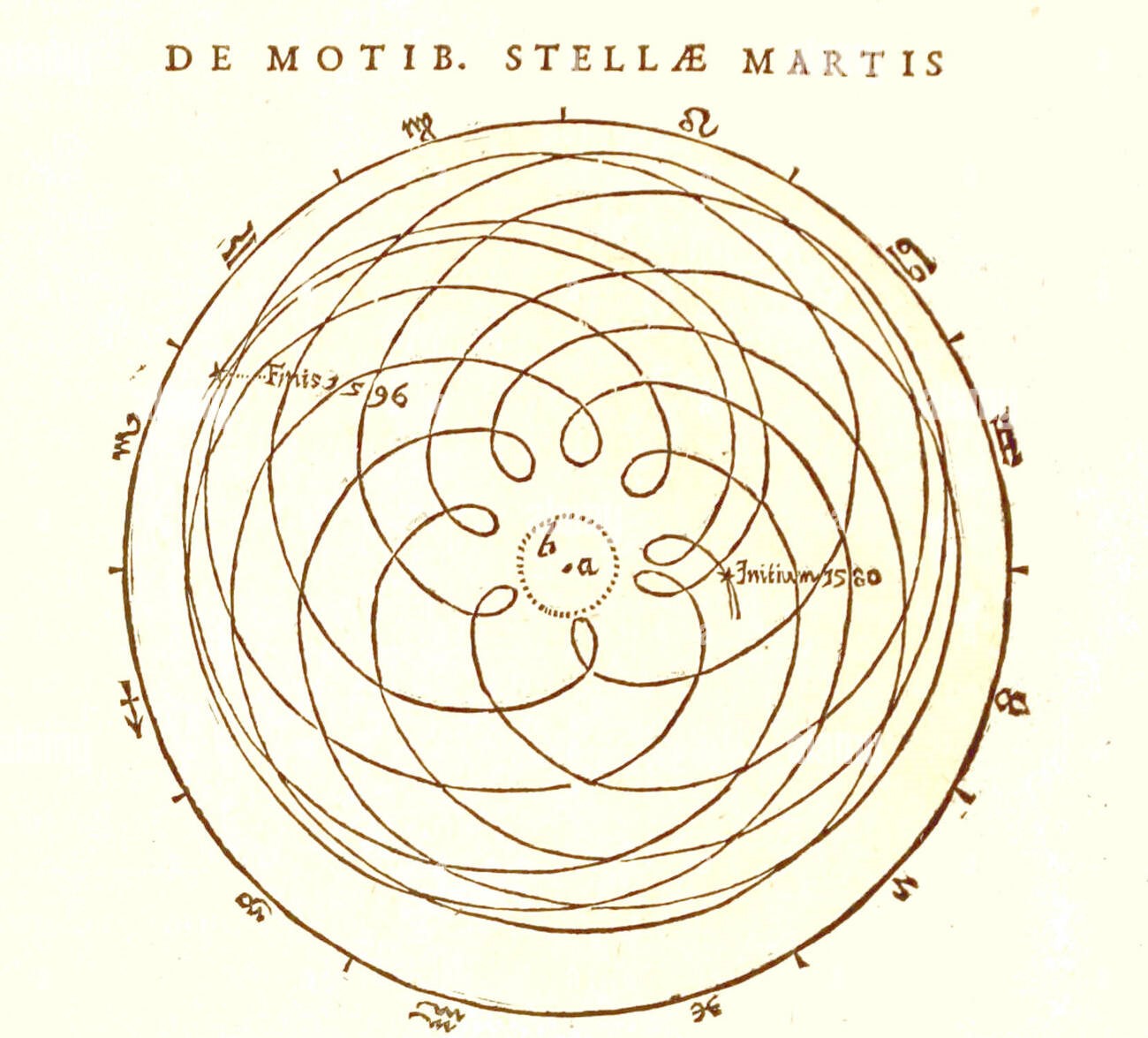

Nella foto la danza all’indietro del pianeta Marte e il moto retrogrado dello stesso pianeta descritto da Keplero.

Oltre alla concezione cosmologica, anche egizie erano le tecniche di ascesa stellare.

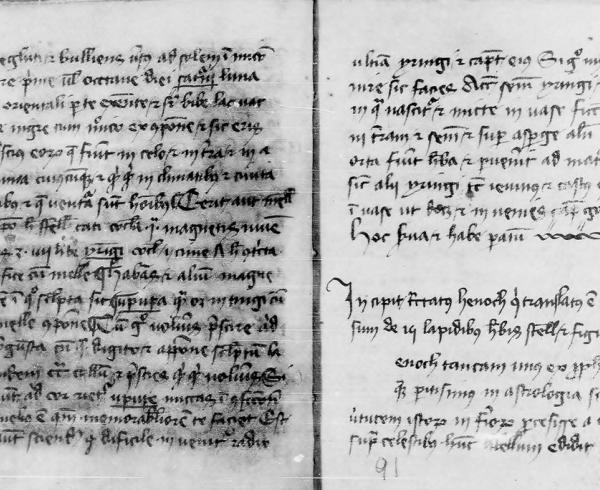

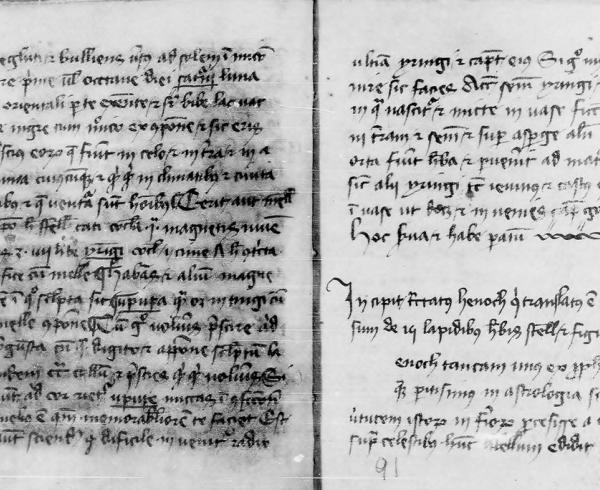

Nella foto il Liber de quindecim stellis di Hermes Abhaidimon, fonte usata per l’abbinamento tra astri, piante e pietre per i riti di ascesa alle stelle.

Nella foto successiva il Grande Papiro Magico di Parigi, chiamato anche manuale per l’immortalità, che riteniamo fosse stato usato da Ottaviano causa la sua origine egiziana alessandrina di poco precedente all’età augustea.

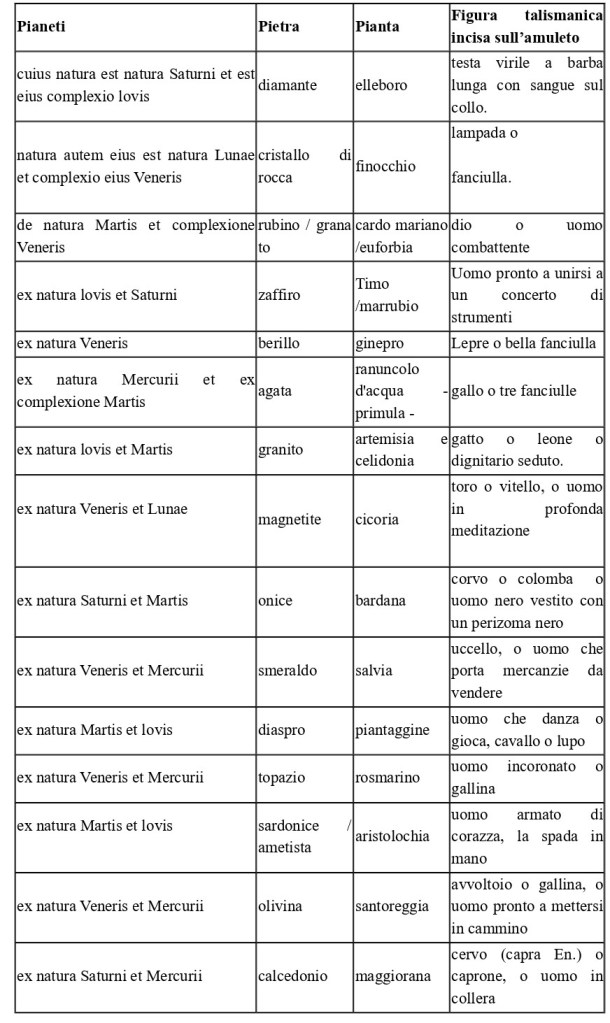

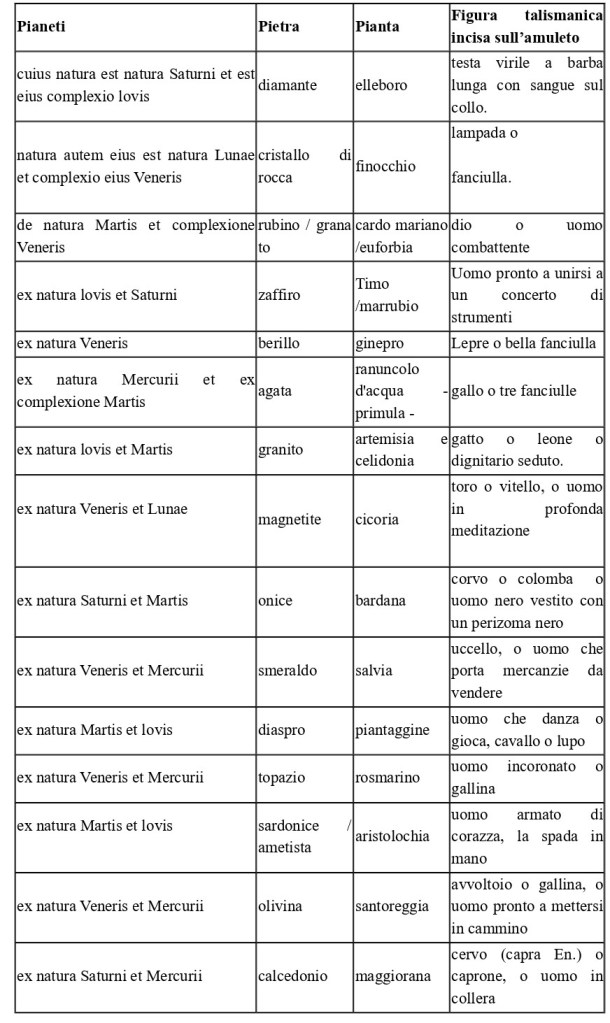

Nelle immagini vediamo un abbinamento tra astri, piante e pietre del Liber de quindecim stellis.

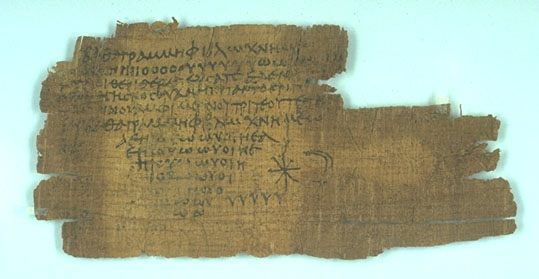

Qui è ritratto un papiro egiziano del terzo secolo dopo cristo: i vocalizzi alla fine così suonano: aeeiooouoieea – eeiooouoiee – eiouoouoie – iouoouoi- ouoououoou uuuuu- oo. Da notare la presenza della Stella e della Luna sui lati del papiro.

Nella foto un’amuleto egiziano di diaspro verde: nella fronte, osiride con due falchi in barca. Sul retro, incisione di vocalizzi aeêiouô. Il diaspro e’ pietra consacrata a marte e giove.

Nella foto un altro amuleto egiziano di diaspro verde. Nella fronte: una figura magica con quattro ali ed una coda. Su retro un’altra vocalizzazione: iaô eulamô ieuêêu a ee êêê iiii ooooo uuuuuu ôôôôôôô.

Nella foto una piantaggine (plantago lanceolata) : trattasi di una specie vegetale associata al diaspro e ai pianeti Marte e Giove.

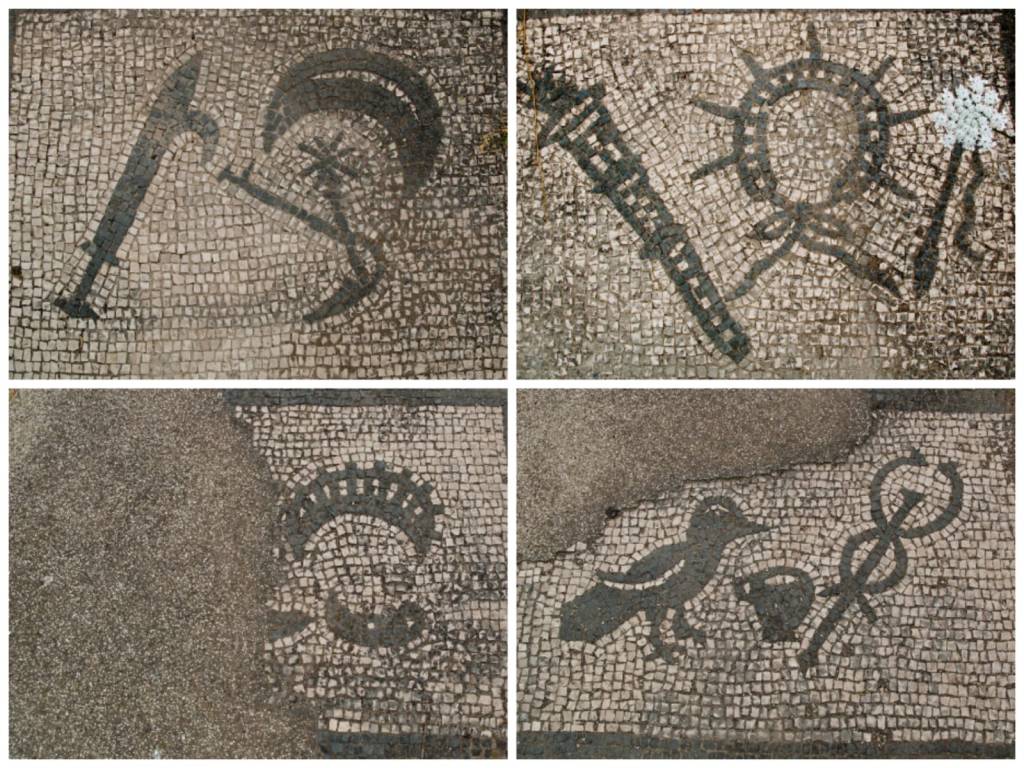

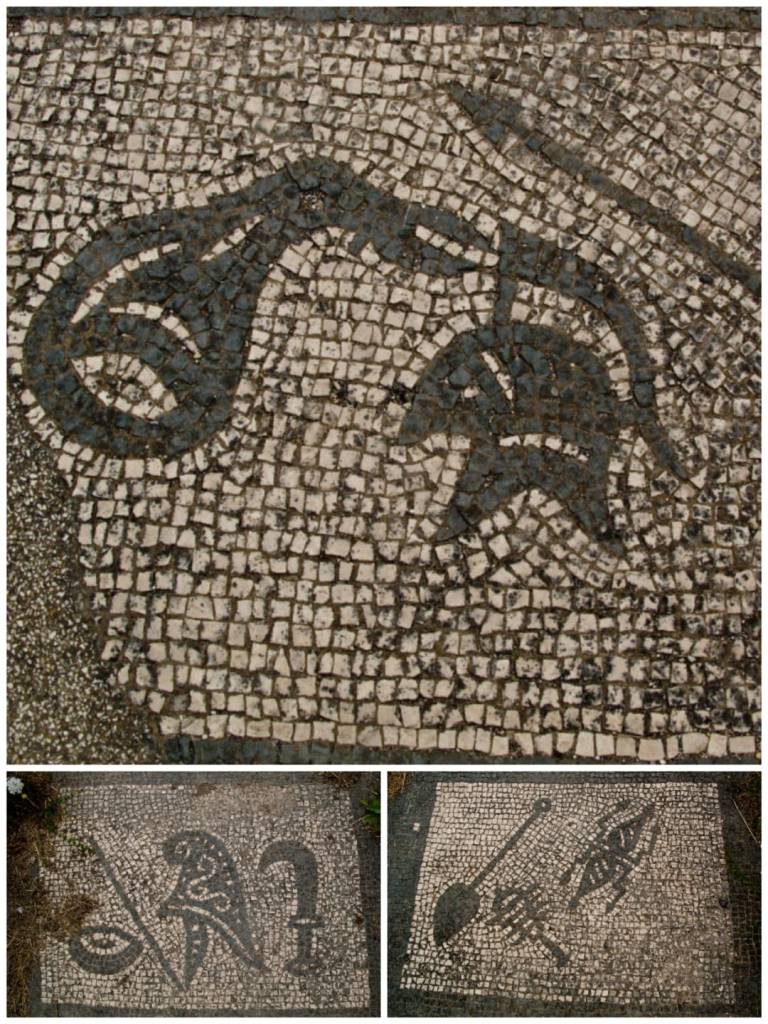

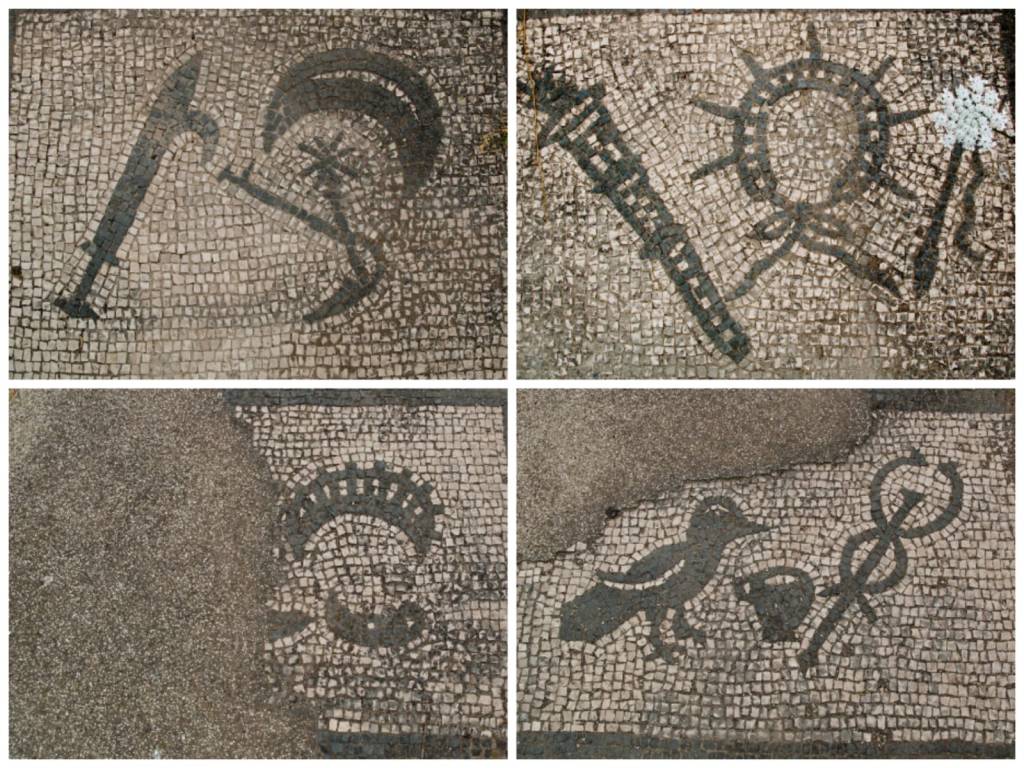

Co riferimento alla stessa tecnica rituale per l’ascesa agli astri vediamo nella foto simboli mitraici per l’ ascesa agli astri rappresentati nel Mitreo di Felicissimus a Ostia Antica risalente alla seconda metà del terzo secolo dopo cristo. Nel primo segmento quelli della Luna, nel secondo quelli del Sole, nel terzo quelli di Venere, nel quarto quelli di Mercurio.

Altri simboli mitraici per l’ ascesa agli astri nel mitreo di Felicissimus sono nel primo segmento quelli di Marte, nel secondo quello di Giove, nel terzo quelli di Saturno.

Le tecniche rituali di ascesa erano, dunque, conoscenze dettagliatamente codificate nelle procedure rituali espresse in parole, suoni, simboli e segni.

Tutto era fondato sulla tesi pitagorica e poi platonica della consustanzialità tra anima e stelle, costituite della stessa sostanza, l’etere, rotante nello stesso senso orario delle stelle.

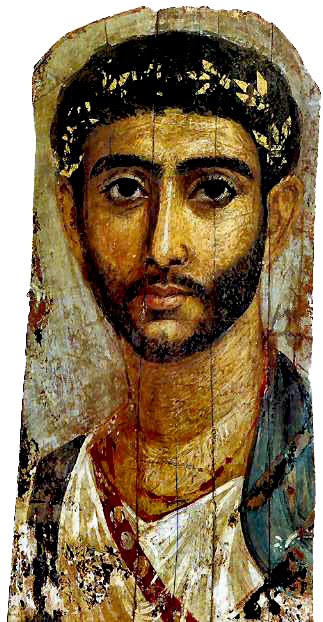

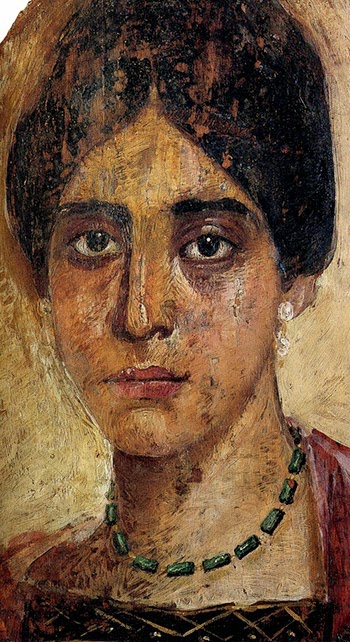

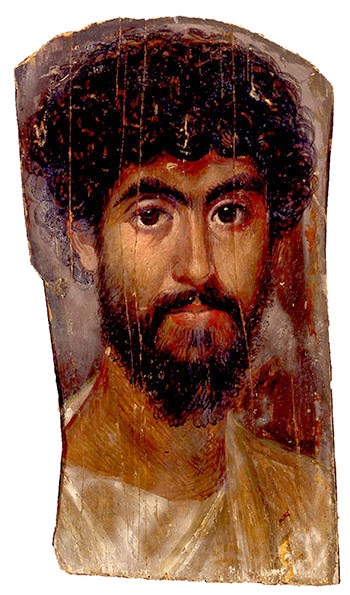

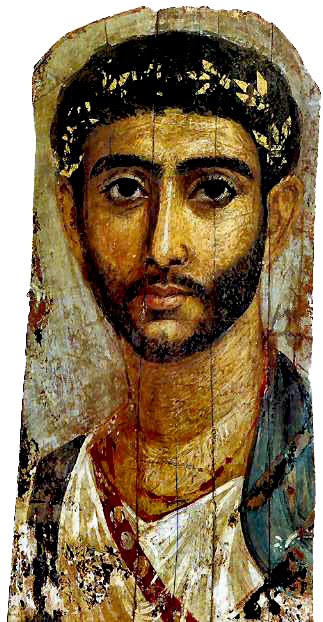

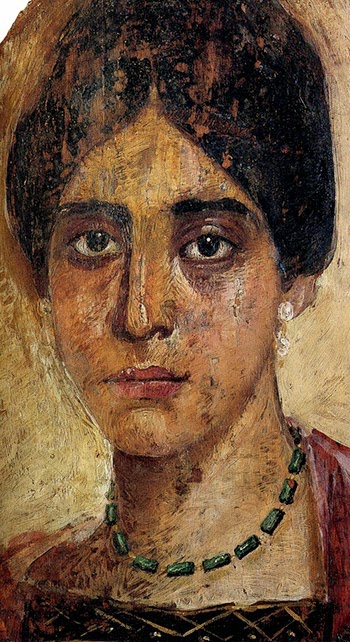

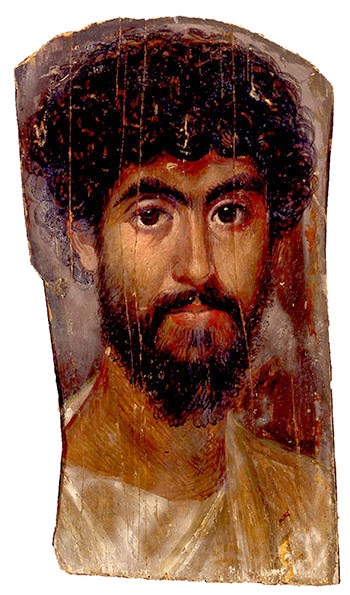

Nelle immagini vediamo scene delle anime nei Campi Elisi. Di seguito ritratti apposti su mummie di epoca romana.

E infine l’immagine di un sarcofago con un giovane ritratto sopra la luna e tra gli astri.

Se si voleva conseguire la peculiare qualità delle stelle, ovvero la perenne immortalità, occorreva seguirne lo stesso moto circumambulando nello stesso senso, in armonia tra corpo e anima, perché gli incorporei si riflettono nei corpi e i corpi negli incorporei, vale a dire il mondo sensibile nel mondo intelligibile e l’intelligibile nel sensibile, come insegnava Hermes Trismegistus

Un imperatore che avesse voluto consacrare, con la sua ascensio ad astra, l’inizio dell’impero fondato su un nuovo patto tra Roma e gli Dei, non avrebbe potuto non rispettare al dettaglio tali tecniche, a scanso di nefaste empietà.

Immaginiamo, dunque, per un momento, Ottaviano durante la celebrazione del rito d’immortalità. Eccolo, vestito di bianco seguire la processione circumambulatoria, guidata dalle Vestali, all’interno del Pantheon. Lo sentiamo, urlare, imperioso, agli astri: Silenzio! Silenzio. Sono un astro che procede con voi e che splende dall’abisso, per come scritto nel Papiro Magico di Parigi.

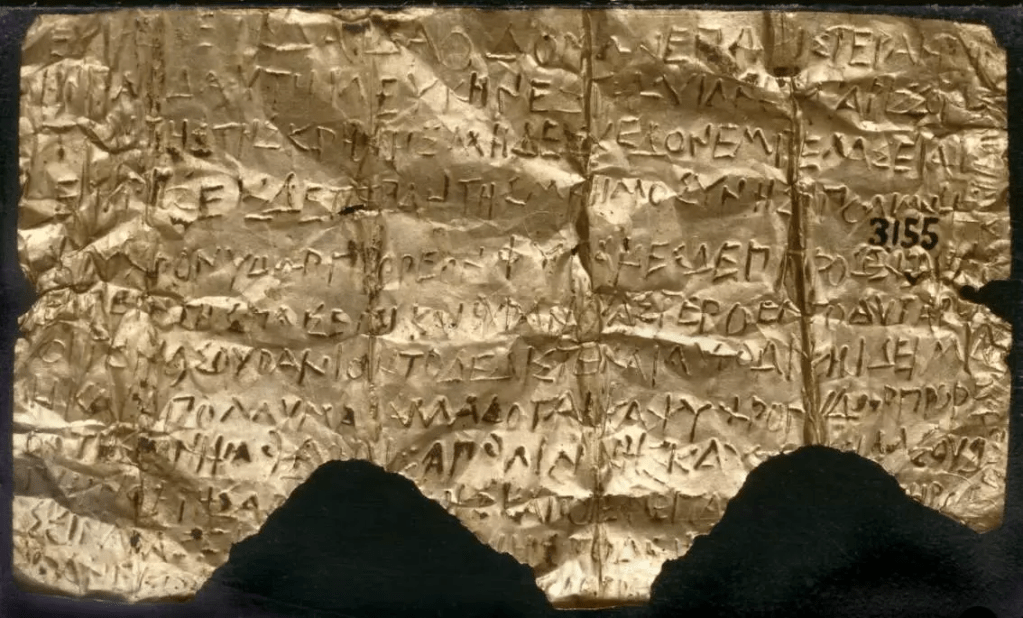

Lo vediamo alla fine stringere nella mano la lamina d’oro orfica su cui è scritto: Sono figlio della terra e del cielo stellato, sono di razza celeste, sappiatelo.

(temi tratti da “Il Pantheon del Cielo” di Aurelio Bruno, 2022, ISBN: 9798844154249)

https://www.termsfeed.com/live/745766ca-724f-4b41-a580-8e4251984660

Disclaimer

Last updated: February 26, 2023

Interpretation and Definitions

Interpretation

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

Definitions

For the purposes of this Disclaimer:

- Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Disclaimer) refers to Il Pantheon del Cielo.

- Service refers to the Website.

- You means the individual accessing the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

- Website refers to Il Pantheon del Cielo, accessible from www.pantheondecoded.org

Disclaimer

The information contained on the Service is for general information purposes only.

The Company assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions in the contents of the Service.

In no event shall the Company be liable for any special, direct, indirect, consequential, or incidental damages or any damages whatsoever, whether in an action of contract, negligence or other tort, arising out of or in connection with the use of the Service or the contents of the Service. The Company reserves the right to make additions, deletions, or modifications to the contents on the Service at any time without prior notice. This Disclaimer has been created with the help of the TermsFeed Disclaimer Generator.

The Company does not warrant that the Service is free of viruses or other harmful components.

External Links Disclaimer

The Service may contain links to external websites that are not provided or maintained by or in any way affiliated with the Company.

Please note that the Company does not guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness, or completeness of any information on these external websites.

Errors and Omissions Disclaimer

The information given by the Service is for general guidance on matters of interest only. Even if the Company takes every precaution to insure that the content of the Service is both current and accurate, errors can occur. Plus, given the changing nature of laws, rules and regulations, there may be delays, omissions or inaccuracies in the information contained on the Service.

The Company is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for the results obtained from the use of this information.

Fair Use Disclaimer

The Company may use copyrighted material which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Company is making such material available for criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research.

The Company believes this constitutes a “fair use” of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the United States Copyright law.

If You wish to use copyrighted material from the Service for your own purposes that go beyond fair use, You must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Views Expressed Disclaimer

The Service may contain views and opinions which are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other author, agency, organization, employer or company, including the Company.

Comments published by users are their sole responsibility and the users will take full responsibility, liability and blame for any libel or litigation that results from something written in or as a direct result of something written in a comment. The Company is not liable for any comment published by users and reserves the right to delete any comment for any reason whatsoever.

No Responsibility Disclaimer

The information on the Service is provided with the understanding that the Company is not herein engaged in rendering legal, accounting, tax, or other professional advice and services. As such, it should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional accounting, tax, legal or other competent advisers.

In no event shall the Company or its suppliers be liable for any special, incidental, indirect, or consequential damages whatsoever arising out of or in connection with your access or use or inability to access or use the Service.

“Use at Your Own Risk” Disclaimer

All information in the Service is provided “as is”, with no guarantee of completeness, accuracy, timeliness or of the results obtained from the use of this information, and without warranty of any kind, express or implied, including, but not limited to warranties of performance, merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose.

The Company will not be liable to You or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information given by the Service or for any consequential, special or similar damages, even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

Contact Us

If you have any questions about this Disclaimer, You can contact Us:

- By email: pantheondecoded@gmail.com

-

LA MUSICA DELLE SFERE

aureliobruno©2023

ASCESA PER MEZZO DELLA MUSICA

Torniamo al Pitagorismo. Esso, vedremo, fornirà a chiave per decodificare la funzione del Pantheon.

I Pitagorici, come disse Aristosseno, “purificavano il corpo con la medicina e l’anima con la musica”.

Pitagora usava soprattutto questo modo di purificazione, come egli chiamava la medicina esercitata mediante la musica, secondo Giamblico La musica, anticamente, fino ai Pitagorici, era ammirata e detta purificazione.

Pitagora “udiva l’armonia dell’universo, intendendo la generale armonia delle sfere e degli astri mossi da queste, che noi non possiamo ascoltare per l’insufficienza della natura” riporta Porfirio.

E gli “Oracoli caldaici” dicono che, dopo che l’anima si spoglia delle vesti delle sfere prima di giungere al Cielo supremo, arrivata al termine, “canta un peana”.

Abbiamo fatto prima cenno alla concezione dell’armonia pitagorica delle sfere che associava toni e semitoni agli otto cieli sopra la Terra.

Plutarco scrive:

Ora, che l’armonia sia augusta, cosa divina e grande, Aristotele, discepolo di Platone, lo segnala in questi termini: “L’armonia è celeste, e la sua natura è divina, tutta bella e meravigliosa. Costituita in valore da quattro membri”, ha due medie una aritmetica e l’altra armonica. Tutto in essa, membri, grandezze ed eccedenze, obbediscono manifestamente al numero e all’isometria in effetti è secondo due intervalli di quattro note che si misura il ritmo del canto.

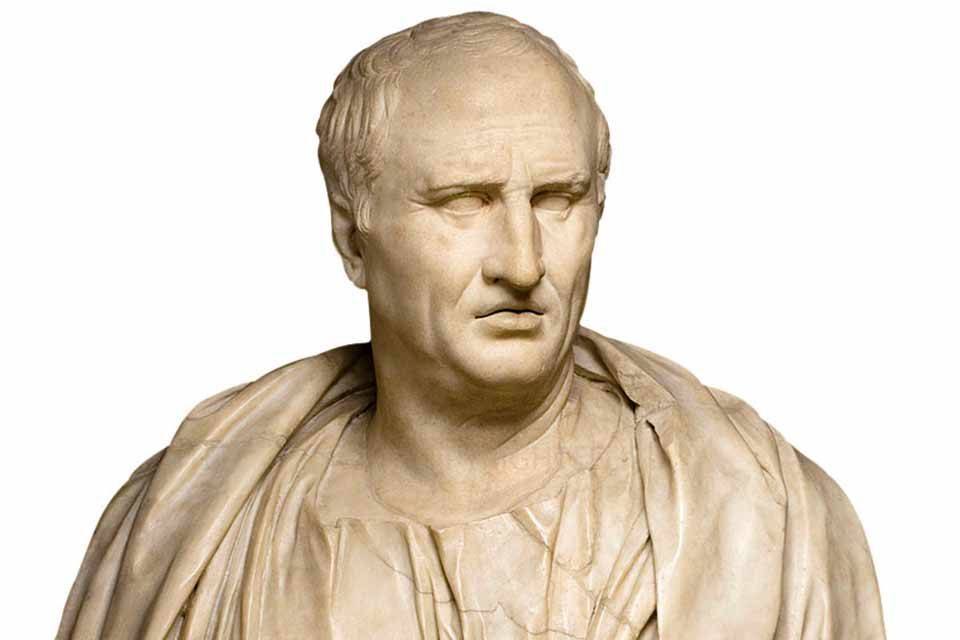

Il sistema pitagorico della gamma armonica planetaria, cui abbiamo prima fatto cenno, fu importato a Roma da Varrone, a sua volta in qualche modo ripreso da Cicerone nel Somnium Scipionis.

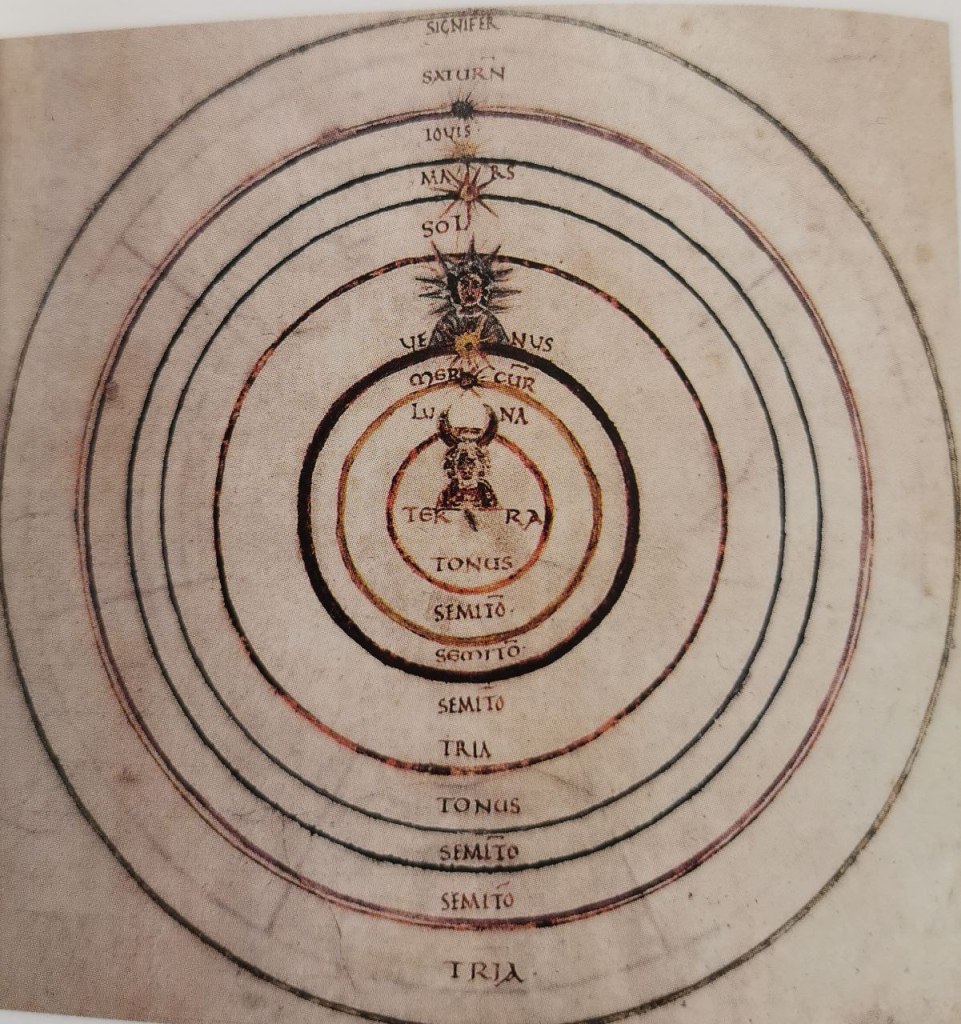

I rapporti di tonalità tra pianeta e pianeta, cioè tra corda e corda della cetra apollinea, erano i seguenti: 1 Luna, ½, Mercurio, ½ Venere, 1 Sole, 1 Marte, ½ Giove, ½ Saturno (½ Cielo delle stelle fisse).

Su probabile influsso di Nigidio Figullo, Igino, ha apportato qualche modifica alla sequenza tonale. Egli associava la gamma alla velocità di rotazione dei pianeti, cioè alla loro presumibile distanza dalla Terra e tra loro. Igino supponeva che ciascun pianeta avesse la stessa velocità di spostamento: più lento era il pianeta, più lontano lo stesso era. L’ordine seguito da Igino è quello caldeo-pitagorico con il Sole al centro, mentre Eratostene, Platone e Aristotele seguivano, come visto, l’ordine egizio, con il Sole subito dopo la Luna, poi gli altri pianeti.

L’analogia fra i movimenti armonici e le rivoluzioni dell’anima facevano dire a Plutarco che la musica esercita sull’anima un’azione tranquillizzante.

Nel “Sogno di Scipione” di Cicerone l’armonia cosmica era il prodotto di otto sfere in movimento, mentre la nona, la sfera della Terra, era immobile. Quando Scipione Emiliano, salito alle regioni celesti, chiede al suo avo: “Ma che suono è questo, così intenso e armonioso, che riempie le mie orecchie?” l’Africano risponde:

“È il suono che, separato in funzione d’intervalli ineguali eppure distinti da una razionale proporzione, è cagionato dalla spinta e dal moto delle sfere stesse che, temperando i toni acuti con i bassi, realizza varie e proporzionate armonie. […] L’orbita stellare suprema, la cui rotazione è la più veloce, si muove con suono più acuto e concitato, mentre questa sfera Lunare, la più bassa, produce il suono più grave. La Terra, infatti, nono globo, poiché resta immobile, rimane sempre fissa in un’unica sede, occupando il centro dell’universo. Le rimanenti otto orbite, poi, all’interno delle quali due hanno la medesima velocità, producono sette suoni distinti dai loro intervalli, il cui numero è, per così dire, il nodo di tutte le cose”.

E qui l’Africano aggiunge che “I dotti che hanno saputo imitare quest’armonia per mezzo delle budelle dei loro strumenti e con i canti si sono aperti la via del ritorno in questo luogo, come quegli altri che, grazie all’eccellenza dei loro ingegni, durante la loro esistenza terrena hanno coltivato gli studi divini.”

Fosse vero quanto riferito da Cicerone, lì si dovrebbero, dunque, incontrare i Mozart o Corelli.

Macrobio commenta scrivendo che l’Anima del Mondo è formata da numeri implicanti un rapporto di proporzione, essendo essa destinata a offrire un’armonia unificante all’universo intero. Essa è intessuta di numeri che generano da se stessi l’armonia musicale, in modo da realizzare, dal movimento al quale imprime il proprio impulso, dei suoni armoniosi, la cui origine stava nel modo di composizione della propria opera. Possiamo così avere

un’idea precisa sia della causa del moto dell’universo, dovuto al solo impulso dell’Anima, sia della necessità dell’armonia musicale che l’Anima imprime al movimento nato da essa, armonia che era in sé innata, fin dall’origine”. “A buon diritto, tutto deve essere, dunque, soggiogato al potere della musica, poiché l’Anima celeste, che tutto anima, deve la sua origine alla musica. Quando imprime al corpo dell’universo un movimento sferico, l’anima produce un suono che è separato in funzione d’intervalli ineguali, eppure distinti da una razionale proporzione, come essa stessa fu da principio intessuta”.

Anche nel papiro greco ermetico “Ricetta d’immortalità – Apathanatismos” si trova, infine, un passo che descrive un flauto celeste, simbolo iniziatico della musica cosmica suonata dalla siringa del Dio Pan:

(…) Poiché vedrai (…) il viaggio degli Dei visibili attraverso il disco solare (il dio, mio padre) ti diverrà palese, e anche ciò che viene detto “il flauto”, da cui parte il vento che è all’opera. Perché vedrai, sospeso sul disco, come un flauto, diretto di fatto dalla parte dell’Occidente, all’infinito, in quanto vento d’Est; se la direzione assegnata è dal lato dell’Est, allora il vento opposto (il vento d’Ovest) si presenterà similmente verso questa regione: vedrai il movimento rotatorio dell’immagine”.

LA MUSICA COSMICA NEL MITO DI ER

Riportiamo ora per esteso il mito platonico di Er, contenuto nel libro X della Repubblica:

Tutti i gruppi di anime, dopo aver trascorso sette giorni nel prato, all’ottavo dovevano alzarsi e partire da lì, per giungere dopo quattro giorni in un luogo da dove scorgevano, distesa dall’alto lungo tutto il Cielo e la Terra, una luce diritta come una colonna, molto simile all’arcobaleno, ma più splendente e più pura. Dopo un giorno di cammino arrivavano lì e vedevano al centro della luce le estremità delle catene che pendevano dal Cielo; questa luce infatti teneva unito il Cielo e ne abbracciava l’intera orbita, come i canapi che fasciano la chiglia delle triremi. A quelle estremità stava appeso il fuso di Ananke, che dava origine a tutti i moti rotatori; l’asta e l’uncino erano d’acciaio, il fusaiolo era una mescolanza di questo e altri metalli. La natura del fusaiolo, che nella forma ricalcava quello usato quaggiù, era la seguente: stando alla descrizione che ne ha fatto Er, bisogna immaginare un grande fusaiolo cavo, completamente svuotato all’interno, nel quale era incastrato un altro più piccolo, come le scatole che si infilano una dentro l’altra, e così un terzo, un quarto e altri quattro ancora. Complessivamente i fusaioli erano dunque otto, incastrati l’uno nell’altro: in alto si vedevano i bordi, simili a cerchi, che formavano il dorso continuo di un solo fusaiolo intorno all’asta; quest’ultima era conficcata da parte a parte dentro l’ottavo. Il primo fusaiolo, il più esterno, aveva il bordo circolare più largo; venivano poi, in ordine decrescente di larghezza, il sesto, il quarto, l’ottavo, il settimo, il quinto, il terzo, il secondo. Il bordo del fusaiolo più grande era variegato, quello del settimo il più splendente, quello dell’ottavo riceveva il suo colore dal settimo, che lo illuminava, i bordi del secondo e del quinto, molto simili tra loro, erano più gialli dei precedenti, il terzo aveva un colore bianchissimo, il quarto rossastro, il sesto veniva per secondo in bianchezza. Il fuso si volgeva tutto quanto su se stesso con moto uniforme, e nella rotazione complessiva i sette cerchi interni giravano lentamente in direzione opposta all’insieme: il più rapido era l’ottavo, seguito dal settimo, dal sesto e dal quinto, che procedevano assieme; in questo moto retrogrado il quarto cerchio sembrava a quelle anime terzo in velocità, il terzo sembrava quarto e il quinto secondo. Il fuso ruotava sulle ginocchia di Ananke. Su ciascuno di quei cerchi, in alto, si muoveva una Sirena, che emetteva una sola nota di un unico tono; ma da tutte otto risuonava una sola armonia. Altre tre donne sedevano in cerchio a uguale distanza, ciascuna sul proprio trono: erano le Moire figlie di Ananke, Lachesi, Cloto e Atropo, vestite di bianco e col capo cinto di bende; sull’armonia delle Sirene Lachesi cantava il passato, Cloto il presente, Atropo il futuro. Cloto con la mano destra toccava a intervalli il cerchio esterno del fuso e lo aiutava a girare, e lo stesso faceva Atropo toccando con la sinistra i cerchi interni; Lachesi accompagnava entrambi i movimenti ora con l’una ora con l’altra mano. Appena giunti, essi dovettero subito presentarsi a Lachesi. Per prima cosa un araldo li mise in fila, poi prese dalle ginocchia di Lachesi le sorti e i modelli di vita, salì su un’alta tribuna e disse: “Proclama della vergine Lachesi, figlia di Ananke! Anime effimere, ecco l’inizio di un altro ciclo di vita mortale, preludio di nuova morte. Non sarà un demone a scegliere voi, ma sarete voi a scegliere il vostro demone.

Ananke (necessità), è simbolo della legge eterna e immutabile che regola l’universo. Qui rappresenta l’ordine razionale e morale del cosmo. Da lei nacquero per partenogenesi le Moire, ovvero le tre dee che presiedevano ai destini individuali degli uomini: Lachesi li assegnava per sorteggio, Cloto li filava, Atropo li rendeva immutabili e tagliava il filo al momento della morte. Per questo Ananke fila il fuso, che gira al centro della colonna di luce (lo axis mundi) e imprime il moto rotatorio a tutte le sfere celesti.

Le Sirene rappresentano, invece, il Cielo delle stelle fisse e i sette pianeti; il loro canto è quindi la musica delle sfere celesti.

Per come ovvio, risulta incomprensibile ai contemporanei la contestuale funzione cosmica e individuale delle Moire. Le stesse decidevano tanto i destini del Cosmo, quanto di ogni singolo individuo.

Com’è possibile?

Tutto è dovuto alla concezione ermetica dell’Uomo come centro dell’universo ed essere in parte divino.

In questa visione, il cosmo girava attorno alla Terra e agli uomini, creando il tempo e decidendo le sorti degli stessi.

Le arti dell’astrologia consistevano allora nel predire tali sorti, mentre quelle teurgiche servivano a influenzarle, se non a modificarle tout court.

Nella presente parte trattiamo delle tecniche teurgiche che sarebbero state usate per influenzare i destini degli uomini, sino a provocarne addirittura la trasformazione in stelle.

Va detto, infine, che mentre l’insieme del fuso ruota da oriente a occidente, i singoli fusaioli ruotano talvolta in senso contrario, a eccezione del primo quello delle stelle fisse.

Proviamo, dunque, a riassumere i fusaioli nella loro identità astronomica.

L’asta, ovvero l’asse del mondo, dei fusaioli era conficcata dentro l’ottavo fusaiolo, ovvero quello della Luna e dello spazio celeste vicino la Terra, più interno e più rapido di tutti.

L’ottavo fusaiolo riceveva la propria luce (il colore) dal settimo fusaiolo, il Sole, che lo illuminava.

Il settimo fusaiolo, quello più splendente, era il Sole (individuato, diversamente da Cicerone, Ermete, etc., subito dopo la Luna, secondo l’ordine egizio), secondo per velocità dopo la Luna.

Il sesto fusaiolo era quello di Venere, secondo in bianchezza, rispetto a quello di Giove. Esso era pure secondo in grandezza e terzo per velocità.

I bordi del quinto fusaiolo, quello di Mercurio, erano simili a quelli del secondo, Saturno ed erano più gialli dei precedenti. Mercurio orbitava con Venere attorno al Sole e nel moto retrogrado aveva la stessa velocità del Sole e Venere che orbitavano insieme.

Il quarto fusaiolo, Marte, era rossastro ed era terzo in grandezza e velocità.

Il terzo fusaiolo, Giove, aveva un colore bianchissimo ed era quarto in velocità.

Il secondo fusaiolo era quello di Saturno: i suoi bordi erano simili a quelli di Mercurio e più gialli dei precedenti.

Il primo fusaiolo, il più esterno, era quello delle Stelle fisse e presenta un bordo circolare più largo ed era variegato di colori.

I fusaioli avevano un bordo od orlo. Da ciò si intuiva che avessero la forma di ciotole o spirali (sphandulos).

Nel mito di Er non è chiaro perché Platone abbia scelto questa disposizione relativa delle dimensioni dei fusaioli: in un passaggio notoriamente criptico del Timeo si trova una disposizione circolare simile per il cosmo derivata dalle “proporzioni di armonia musicale”.

La descrizione di questa armonia nel Timeo è tratta dalla filosofia matematico-musicale del suo contemporaneo Archita di Taranto, Pitagorico del 4 ° secolo a.C.. Tra le altre cose, Archita aveva sviluppato teorie del suono in funzione del movimento e di diverse varietà di scale musicali derivate da particolari rapporti. Concepì, dunque, intervalli musicali di quinte (3: 2), quarti (4: 3), ottave (2: 1), toni (9: 8) e semitoni (256: 243).

Queste relazioni armoniche costituiscono una manifestazione matematica emergente dai fenomeni naturali e sono esattamente usate come tali da Platone nel Timeo, sebbene non sia del tutto ovvio come questi intervalli si manifestassero fisicamente.

Di seguito una tabella che riassume le qualità e le dimensioni dei fusaioli platonici (ns adattamento dal Newsome):

Fusaiolo più piccolo o più largo 1°(8°) 2°(7°) 3°(6°) 4°(5°) 5°(4°) 6°(3°) 7°(2°) 8°(1°) Sfera Luna Sole Venere Mercurio Marte Giove Saturno Stelle fisse Grandezza relativa di ciascun fusaiolo 4° 5° 2° 6° 3° 7° 8° Più piccolo 1° Più grosso Colore di ogni fusaiolo Riflesso dal Sole Più brillante 2° più brillante giallognolo Rosso pallido Più bianco giallognolo multicolorate Velocità di rotazione contraria a quella delle stelle fisse Più veloce veloce veloce veloce media lento Più lento Rotazione giornaliera (della Necessità) Di seguito la rappresentazione grafica dei rapporti matematici sopra citati, sempre tratta da Newsome.

Come vedremo in seguito, tale rappresentazione dei fusaioli, a forma di scudo, riproduce con sorprendente esattezza la cupola capovolta del Pantheon.

Sentiamo ora come Platone espone, nel Timeo, il rapporto tra i diversi movimenti astrali:

Dopoché ciascuno degli astri, che sono necessari per la formazione del tempo, giunse nell’orbita che gli era più adatta, e i loro corpi, collegati con legami animati, divennero esseri viventi, e appresero il loro compito, allora secondo il movimento dell’altro che è obliquo e passa attraverso il movimento del medesimo e ne è dominato, gli uni percorsero un’orbita maggiore, gli altri un’orbita minore, e quelli che percorrevano un’orbita minore erano più rapidi, quelli che percorrevano un’orbita maggiore erano più lenti. Grazie al movimento del medesimo gli astri che giravano più rapidamente sembravano essere raggiunti da quelli che giravano più lentamente, anche se li raggiungevano: infatti questo movimento volgeva tutte le loro orbite a spirale, e muovendosi gli uni in un senso e gli altri in senso contrario, faceva in modo che quel pianeta che si allontanava più lentamente da questo movimento, che è il più veloce, sembrasse il più vicino.

I numeri del Timeo hanno un significato che va oltre il loro significato matematico; la matematica è impiegata analogicamente per esprimere una parentela intrinseca tra principi metafisici e i loro effetti di bellezza e ordine nella realtà. Di conseguenza, una scala musicale fatta di numeri altisonanti (rapporti= logoi) rende possibile la contemplazione simbolica (symbolike theoria) dei paradigmi nei loro effetti o immagini.

La concezione platonico-pitagorica del mousikè corrisponde a un’ampia nozione di musica che racchiude l’ordine armonioso di ogni cosa nell’universo.

Per i Pitagorici, la derivazione del numero e la mediazione della musica ha prodotto l’intero cosmo, come dice Aristotele nella Metafisica:

[i Pitagorici] videro che le modificazioni e le proporzioni delle scale musicali erano esprimibili in numeri; poiché, allora, tutte le altre cose sembravano, nella loro natura essere modellate sui numeri, e i numeri sembravano essere la prima cosa della natura, supponevano che gli elementi dei numeri fossero gli elementi di tutte le cose, e che l’intero cielo fosse una scala musicale (armonia) e un numero. E tutte le proprietà di numeri e scale che poterono dimostrare di concordare con attributi, parti e l’intera disposizione dei cieli, hanno raccolto e inserito nel loro schema.

Ci sono echi di questa concezione pitagorica nel racconto di Platone dell’origine dell’ordine dei circuiti celesti e della loro dipendenza dai cerchi armonici e dagli intervalli musicali all’interno dell’Anima Mundi composta come una scala musicale (Timeo 35b-37a). Secondo il Timeo l’universo è un kosmos (insieme splendidamente disposto), come risultato di una combinazione di armonia (un armonioso adattarsi insieme/sintonizzazione, dal verbo harmottein) e taxis (ordine e regolarità).

Ma ritorniamo all’illustrazione dei fusaioli platonici.

Platone scrive nel mito di Er che “su ciascuno di quei cerchi, in alto, si muoveva una Sirena, che emetteva una sola nota di un unico tono; ma da tutte otto risuonava una sola armonia”. Le Sirene non erano le sole a cantare. Sedute su troni equidistanti, lungo i bordi, vi erano le tre Moire, “le figlie della Necessità” (come si vede nell’illustrazione del Newsome). Lachesi cantava il passato, Cloto il presente, Atropo il futuro.

Esse erano anche responsabili della regolazione delle rotazioni dei fusaioli.

“Cloto con la mano destra toccava a intervalli il cerchio esterno del fuso (quello delle stelle fisse) e lo aiutava a girare.”

Cloto era dunque responsabile per il mantenimento della rotazione quotidiana dei cieli. Atropo invece toccava con la sinistra, ovvero in direzione contraria alla rivoluzione delle stelle fisse, i cerchi interni, quelli delle sfere planetarie.

Lachesi accompagnava entrambi i movimenti ora con l’una ora con l’altra mano.

Cloto era la Moira che canta il presente. Con la mano destra, regola la velocità di rotazione della sfera più esterna come se facesse girare la ruota di una roulette. In altre parole, essa regola il ritmo quotidiano, fisso che costituisce la base di tutto il movimento meccanico e immutabile dei cieli, quello del Circolo dello Stesso.

È all’interno di questa sfera più ampia che le altre sfere sono trasportate. Il Sole, la Luna e i pianeti hanno i movimenti loro propri, ma i loro movimenti principali sono determinati in relazione alla sfera delle stelle fisse, il cui movimento costituisce il più evidente di tutti i cicli.

Atropo, con la mano sinistra, è invece responsabile della regolazione delle rotazioni delle sfere interne.

“In altre parole lei manteneva la velocità delle sette sfere con diverse traiettorie radiali, lanciate contro il movimento della ruota della roulette esterna.”

Atropo è la Moira che canta il futuro. È dalla conoscenza dei movimenti delle sfere interne, infatti, che è possibile trarre pronostici e previsioni. In particolare, la conoscenza dei cicli stagionali (“sapienti”) del Sole e della Luna è cosa di somma importanza per l’agricoltura, l’attività e gli affari umani.

Nel Timeo leggiamo che il giorno e la notte “rappresentano il periodo del movimento circolare unico e più sapiente: il mese nacque invece quando la Luna raggiunge il Sole dopo aver percorso la sua orbita, e l’anno quando il Sole ha percorso la sua orbita.”

Più arduo è cercare di comprendere il ruolo di Lachesi, che canta il passato e controlla alternativamente l’interno e l’esterno delle sfere con entrambe le mani, la destra e la sinistra, consentendo l’accelerazione e la decelerazione degli astri.

È ragionevole presumere che Platone si riferisse ai moti meno prevedibili nei cieli: ovvero ai moti retrogradi, quelli del Circolo del Diverso, di cui abbiamo parlato prima, e alle variazioni di velocità apparente dei pianeti.

Egli scrive nel Timeo:

Quanto ai periodi degli altri pianeti, poiché gli uomini non li conoscono, salvo alcuni pochi, non sono stati neppure nominati e non si misurano in numeri, mediante l’osservazione, i loro rapporti reciproci, sicché, così per dire, gli uomini non sanno che il tempo è misurato anche dai loro giri, infinitamente molteplici e straordinariamente vari: non di meno è tuttavia possibile capire che il numero perfetto del tempo realizza l’anno perfetto allorquando le velocità di tutti e gli otto periodi, compiendosi reciprocamente, ritornano al punto di partenza, misurate secondo “L’orbita dello Stesso” che si muove in modo uniforme.

Newsome afferma che, giacché i pianeti (letteralmente, planetes ovvero “vagabondi”) avevano movimenti così intricati, riferiti a moti retrogradi e simili, essi non fossero utili per le previsioni nel futuro.

Poiché “non si misurano i loro rapporti reciproci” (tra pianeti e tra questi e il Sole e la Luna), ciò avrebbe precluso la previsione di dove e quando si sarebbe trovato un pianeta in relazione ai tempi e ai luoghi prevedibili del Sole e della Luna.

Dunque, l’autore sospetta che siano stati più probabilmente utili per localizzare eventi nel passato. Da qui la loro associazione con Lachesi. Newsome fa un esempio: “Marte potrebbe essere stato in Bilancia quando un terremoto ha colpito Atene molti anni fa”.

Crediamo più verosimile ritenere che il “canto del passato” di Lachesi sia da riferire ai pianeti proprio in ragione del loro moto retrogrado. Tale moto costituisce, infatti, uno “strappo” nel “continuum spazio temporale” dell’immutabile rotazione stellare. Ritornando indietro (verso il passato), il moto retrogrado dei pianeti interrompe la regolarità dei corsi ciclici.

Il fatto che Lachesi utilizzasse entrambe le mani, consentendo accelerazioni, decelerazioni e ritorni all’indietro, non può non riportare alla memoria quanto detto sulle lustrationes labirintiche: cerimonie di purificazione basate su moti in avanti e indietro (con antistrofe musicali, vedi avanti), potrebbero essere immagine rituale della superna gestualità di Lachesi.

Detto dell’aspetto simbolico gestuale, ritorniamo sul tema musicale. Anche perché è arrivato il momento di un chiarimento concettuale. Se Lachesi con il suo movimento determina un ritorno al passato che coincide con il moto retrogrado di alcuni pianeti, per come sopra asserito, tale moto contrario (detto da Macrobio, tra poco lo vedremo, antistrofa) non può non determinare un cambio della direzione musicale. Ovvero, la scala musicale, secondo noi, da ascendente, come nell’ascesa di Filologia (ne parleremo a breve), dovrebbe, in senso inverso cioè in antistrofa, tramutare la scala musicale da ascendente in discendente.

Su un immaginario fusaiolo o piramide, se si vuole, il movimento verso l’alto dei cieli sarebbe sviluppato con note ascendenti, quello in discesa dal cielo, con note discendenti.

Se si considera il cosmo descritto nel Timeo è possibile che i toni cantati da ciascuna Sirena fossero determinati dai raggi armonici pitagorici sopra esposti.

In proposito, un tentativo (imperfetto) di ricostruzione del modello platonico di cosmo musicale è stato quello operato da Stephenson sulla base della distanza (raggi) dalla Terra qui di seguito esposto.

Sfera Terra Luna Sole Venere Mercurio Marte Giove Saturno Stelle fisse Raggi misurati dal centro della terra N.a. 1 2 3 4 8 9 27 ? Intervalli ricostruiti per il pianeta precedente silenzio 1(1:0) 1:2 2:3 3.4 4.8 (1:2) 8:9 9:27 (1:3) 27? Intervalli musicali dal più basso al più alto N.a. Unisono?Tono? ottava quinta quarta ottava tono Ottava + quinta ? Altra possibilità è che i toni fossero correlati con le velocità orbitali per come detto da Cicerone nel Sonno di Scipione.

Nei successi paragrafi vedremo altre ricostruzioni più convincenti di armonia cosmica.

Vorremmo chiudere tornando a Platone nel Timeo:

E l’armonia, dotata di movimenti affini ai circoli della nostra anima, a chi con intelligenza si serve delle Muse non sembra utile, come si crede ora, a procurare un piacere irragionevole: ma essa è stata data dalle Muse per ordinare e rendere consono con se stesso il circolo della nostra anima che fosse diventato discorde.

Attraverso il filosofo Macrobio, pur essendo nato tre secoli e oltre dopo Augusto (385 circa –430 circa), possiamo tracciare un affresco complessivo del pensiero neoplatonico.

Fu studioso di astronomia e, come quasi tutti all’epoca, seguiva la teoria geocentrica, che pone la Terra, stazionaria, in posizione centrale rispetto all’Universo.

Scrisse un commentario in due libri del Somnium Scipionis di Cicerone, dedicato al figlio Eustazio.

L’obiettivo di Macrobio è quello di mostrare come l’intero pensiero antico e soprattutto le dottrine neoplatoniche siano contenuti nel testo ciceroniano. Egli sostiene che Dio, origine di tutto ciò che esiste, crea la Mente (nous), e che la Mente crea l’Anima del Mondo; l’Anima del Mondo, incorporea, “volgendo indietro lo sguardo”, degenera poco a poco fino a diventare matrice dei corpi.

Nel suo Commentario, Macrobio si dilunga sul tema dei rapporti matematici che presiedono all’armonia.

Leggiamo qualche passaggio del Libro II, nella nostra traduzione, ove specificamente egli tratta della musica delle sfere. E’ un tema di raro pregio per le informazioni contenute. Cominciamo da uno stralcio del capitolo I.

Ora è ben noto che nei cieli nulla accade per caso o per caso, e che tutte le cose di sopra procedono ordinatamente secondo la legge divina. Perciò è indiscutibilmente giusto presumere che i suoni armoniosi provengano dalla rotazione delle sfere celesti, poiché il suono deve venire dal movimento, e la ragione, che è presente nel divino, è responsabile per i suoni essendo melodiosi

Pitagora fu il primo di tutti i greci ad afferrare questa verità. Capì che i suoni che uscivano dalle sfere erano regolati dalla Ragione divina, che è sempre presente nel Cielo, ma ebbe difficoltà a determinarne la causa sottostante e a trovare modi per scoprirla. Quando fu stanco della sua lunga indagine su un problema così fondamentale eppure così recondito, un avvenimento casuale gli presentò ciò che il suo pensiero profondo aveva trascurato.

Da qui in poi Macrobio narra della nota leggenda della scoperta dell’armonia fatta da Pitagora in un officina di fabbro. Passa poi a trattare delle combinazioni armoniche.

Presentando l’argomento una certa oscurità dobbiamo, per motivi di sintesi, rimandare alla spiegazione matematica di tali rapporti nel testo citato in nota.Continuiamo al capitolo II.

Così l’Anima Mundi, che ha mosso il corpo dell’universo al movimento che ora vediamo, deve essere intrecciata con quei numeri che producono l’armonia musicale per rendere armoniosi i suoni che ha instillato dal suo impulso vivificante. Ha scoperto la fonte di questi suoni nel tessuto della sua stessa composizione.”

Platone riferisce, come abbiamo detto prima, che il divino Creatore dell’Anima, dopo averla tessuta di numeri disuguali, riempiva gli intervalli fra loro di sesquialteri, sesquiterziani, superottave, e semitoni. Nel passaggio successivo Cicerone mostra molto abilmente la profondità della dottrina di Platone: “Cos’è questo suono grande e piacevole che riempie le mie orecchie?” “Questa è una concordia di toni separati da intervalli disuguali ma tuttavia accuratamente proporzionati, causati dal rapido movimento delle sfere stesse.” Vedete qui come fa menzione degli intervalli e afferma che sono diseguali e che sono separati in proporzione; giacché nel Timeo di Platone gli intervalli dei numeri disuguali sono intercalati da numeri a essi proporzionali, cioè sesquialteri, sesquiterziani, superottave e mezzitoni, nei quali è abbracciata ogni armonia. Quindi vediamo chiaramente che queste parole di Cicerone non sarebbero mai state comprensibili se non avessimo incluso una discussione dei sesquialteri, sesquiterziani e superottave inseriti negli intervalli, e dei numeri con cui Platone costruì l’Anima del Mondo, insieme al motivo per cui l’Anima era intessuta di numeri che producevano armonia. Così facendo non abbiamo solo spiegato le rivoluzioni nei cieli, delle quali solo l’Anima è responsabile; abbiamo anche mostrato che i suoni che ne scaturivano dovevano essere armoniosi, perché erano innati nell’Anima che spingeva l’universo al movimento.

Continuiamo col terzo capitolo del II libro.

In una discussione nella Repubblica sul moto vorticoso delle sfere celesti, Platone dice che una Sirena siede su ciascuna delle sfere, indicando così che dai moti delle sfere le divinità erano fornite di canto; poiché una Sirena che canta è equivalente a un dio nell’accettazione greca della parola.” Inoltre, i cosmogonisti hanno scelto di considerare le nove Muse come il canto armonioso delle otto sfere e l’unica armonia predominante che proviene da tutte loro.” Inoltre, chiamano Apollo, dio del Sole, il “capo delle Muse”, come a dire che è il capo e il capo delle altre sfere, così come Cicerone, riferendosi al Sole, lo chiamò capo, capo e regolatore degli altri pianeti, mente e moderatore dell’universo. Anche gli Etruschi riconoscono che le Muse sono il canto dell’universo, poiché il loro nome è Camenae, una forma di Canenae, derivata dal verbo canere. Che i sacerdoti riconoscano che i cieli cantano è indicato dal loro uso della musica nelle cerimonie sacrificali, poiché alcune nazioni preferiscono la lira o la cetra, e alcuni flauti o altri strumenti musicali. Anche negli inni agli dei si mettevano in musica i versi della strofa e dell’antistrofa, in modo che la strofa rappresentasse il moto in avanti della sfera celeste e l’antistrofa il moto inverso delle sfere planetarie; questi due movimenti produssero il primo inno della natura in onore del Dio Supremo. Anche nelle processioni funebri, le usanze dei diversi popoli hanno decretato l’uso dell’accompagnamento musicale, per la credenza che le anime dopo la morte ritornano alla sorgente della dolce musica, cioè al Cielo. Ogni anima in questo mondo è allettata da suoni musicali così che non solo coloro che sono più raffinati nelle loro abitudini, ma anche tutti i popoli barbari, hanno adottato canti dai quali sono infiammati di coraggio o corteggiati al piacere; poiché l’anima porta con sé nel corpo un ricordo della musica che conobbe nel Cielo, ed è così affascinata dal suo fascino che non c’è seno così crudele o selvaggio da non essere afferrato dall’incantesimo di un tale appello. (…) Abbiamo appena spiegato che le cause dell’armonia sono ricondotte al Anima Mundi, essendo state intrecciate in essa; l’Anima Mundi, inoltre, fornisce a tutte le creature la vita: “Di qui la razza dell’uomo e degli animali, la vita delle cose alate e le strane forme che l’oceano porta sotto il suo pavimento di vetro”. Di conseguenza è naturale che ogni cosa che respira sia rapita dalla musica poiché l’Anima celeste che anima l’universo è scaturita dalla musica. Nell’accelerare le sfere al movimento produce toni separati da intervalli disuguali ma tuttavia accuratamente proporzionati, secondo il suo tessuto primordiale.

Macrobio nel passo qui riportato fa menzione di strofa e antistrofa. L’assunto del filosofo platonico era che la strofa rappresentasse il moto in avanti della sfera celeste mentre l’antistrofa il moto inverso delle sfere planetarie.

Dato che, per dirla come Ermete, ciò che è in Cielo è come ciò che è in Terra, secondo noi, il movimento a strofa rappresenterebbe il moto ascensionale verso le stelle, mentre il moto inverso dell’antistrofa il moto discensionale.

Ovvero se si vuole ascendere alle stelle, per “apoteosizzarsi”, bisogna usare versi musicali con note in scala ascendente, mentre per chiedere la discesa della potenza divina dall’alto sulla Terra occorrono note in scala discendente.

Ora dobbiamo chiederci se questi intervalli, che nell’Anima incorporea sono appresi solo nella mente e non dai sensi, governano le distanze tra i pianeti in bilico nell’universo corporeo. Archimede, infatti, credeva di aver calcolato in stadi le distanze tra la superficie terrestre e la Luna, tra Luna e Mercurio, Mercurio e Venere, Venere e il Sole, il Sole e Marte, Marte e Giove, Giove e Saturno, e che aveva anche stimato la distanza dall’orbita di Saturno alla sfera celeste. Ma le figure di Archimede furono respinte dai platonici per non aver rispettato gli intervalli nelle progressioni dei numeri due e tre. Decisero che non poteva esserci che un’opinione, che la distanza dalla Terra al Sole fosse il doppio di quella dalla Terra alla Luna, che la distanza dalla Terra a Venere fosse tre volte maggiore di quella dalla Terra al Sole, che la distanza dalla Terra a Mercurio era quattro volte maggiore che dalla Terra a Venere, che la distanza dalla Terra a Marte era nove volte maggiore della distanza dalla Terra a Mercurio, che la distanza dalla Terra a Giove era otto volte più grande che dalla Terra a Marte, e che la distanza dalla Terra a Saturno era ventisette volte più grande che dalla Terra a Giove. Porfirio include questa convinzione dei platonici nei suoi libri che illuminavano le oscurità del Timeo, e dice che credevano che gli intervalli nell’universo corporeo, che erano pieni di sesquiterziani, sesquialteri, superottave, mezzitoni e una leimma, seguissero il modello del tessuto dell’Anima, e l’armonia era tale che i suoi intervalli proporzionali erano intrecciati nel tessuto dell’Anima e che sono stati anche iniettati nell’universo corporeo che è vivificato dall’Anima.” Da qui l’affermazione di Cicerone, che l’armonia celeste è una concordia di toni separati da intervalli disuguali ma tuttavia accuratamente proporzionati, è sotto tutti gli aspetti saggia e vera.

Con le tesi sopraccitate, Macrobio avrà, supponiamo, partecipato a qualche complessa contesa erudita sul tema della platonicità dei contenuti del Somnium ciceroniano.

Certamente, non avrebbe potuto immaginare che ci avrebbe fornito, secoli dopo, anche a noi “scimmie vestite” con lo smartphone, alcuni argomenti per l’interpretazione della funzione del Pantheon.

ASCESA PER MEZZO DELL’ARMONIA DELLE SFERE E DELLE MUSE

Per Omero le Muse sono nove, sono figlie di Zeus e stanno sull’Olimpo. Nel prologo della sua Teogonia Esiodo parla anch’egli di nove Muse, “arricchendo il Cielo e gli astri di divinità”.

Riguardo alla denominazione di “Muse”, Proclo diceva che, poiché, la filosofia, platonicamente “musica grandissima”, fa muovere le nostre potenze psichiche in modo armonioso rispetto agli enti e ai loro movimenti, noi entriamo in accordo con l’universo in quanto rendiamo i nostri cicli dell’anima simili a quelli dell’universo, è per questo che noi ricaviamo da questa ricerca il nome che diamo alle Muse. E continua:

[…] E in verità noi sappiamo che le Muse sono quelle che inculcano nelle anime la ricerca della verità, nei corpi la molteplicità delle potenze, ovunque la verità delle armonie.

Dunque, le Muse sono Dee delle sfere, ruolo originariamente attribuito alle Sirene, poi assegnato alle Muse, che risultano essere loro superiori. Diceva infatti Proclo che la divisione del Cielo fosse in otto sfere, quella di tutto il Mondo in nove sfere, e che la prima divisione, nella Repubblica di Platone, fosse stata dedicata alle Sirene, mentre la seconda a tutto l’insieme delle Muse, sotto le quali sono le Sirene.

In uno dei discorsi attribuiti da Giamblico a Pitagora, le Muse erano deputate a vegliare sull’armonia universale. Esse non venivano, però, identificate con ognuna delle sfere planetarie. Pitagora aveva suggerito di costruire un tempio alle Muse per mantenere la concordia nella città,

perché queste Dee, diceva, portavano tutte insieme lo stesso nome, erano note alla tradizione come una comunità e si compiacevano in sommo grado del culto comune; e poi il coro delle Muse era sempre uno e costantemente il medesimo, e in più racchiudeva in sé accordo, armonia e ritmo, cioè tutto quanto crea la concordia. Infine mostrava come il loro potere si estendesse non solo fino ai più alti principi scientifici ma anche all’accordo e all’armonia dell’universo.

Con riguardo alle Muse, Macrobio scrive nel Commentario:

Anche i teologi hanno inteso con le nove Muse gli accenti melodiosi delle otto sfere celesti con il supremo accordo unico che risulta dal tutto. Ecco perché Esiodo, nella sua Teogonia, dà all’ottava musa il nome di Urania: perché dopo le sette sfere erranti, che sono poste sotto di essa, l’ottava, la sfera stellare che sta loro di sopra, è il Cielo propriamente detto; e per farci intendere che ce n’è una nona, più grande di tutte, che risulta dall’unione di tutte le armonie assieme, aggiunge: Calliope: è questa fra tutte egregia, significando con questo nome che la nona Musa è designata dalla dolcezza stessa della voce. Calliope, infatti, significa in greco “dotata di bellissima voce”, e per indicare espressamente che è un insieme armonico risultante da tutte le altre, il poeta le assegna un’espressione che indica l’universalità: è fra tutte egregia.

E Proclo, sullo stesso tema:

gli Antichi hanno dato la sovrintendenza sull’Universo alle Muse e ad Apollo Musagete, l’uno che provvede all’unificazione dell’armonia complessiva; le altre che mantengono insieme la progressione divisa di questa armonia, avendo accordato il loro numero con quello delle otto sirene della Repubblica. Le Muse e Apollo Musagete sono infatti stati creati dal Demiurgo, “così come la catena di Ermete. In lui dunque vi sono anzitutto il calcolo demiurgico e l’armonia, giacché l’uno appartiene a Ermete, l’altra ad Apollo e, in quanto colma di entrambi, l’anima partecipa sia al calcolo che all’armonia.

In epoca successiva Marsilio Ficino fece riferimento a Le nozze di Filologia e Mercurio di Marziano Capella quando, nel trattare dell’armonia delle sfere, dice che Urania occupa la sfera più esterna del Firmamento stellato, che gira velocemente, echeggiando di un suono acuto, Polimnia regola la sfera di Saturno, Euterpe quella di Giove, Erato controlla la sfera di Marte, Melpomene la sfera mediana, dove il Sole abbellisce l’universo con luce fiammante, Terpsicore si unisce all’oro di Venere, Calliope abbraccia il giro del Cillenio, ossia Mercurio, Clio pone la sua residenza nella sfera più vicina ossia la Luna, la quale risuona di note gravi, con modi musicali più rochi; Talia invece è abbandonata sulla Terra, priva di suono. Questa rappresentazione coincide con quella di Gaffurio ove, accanto ad Apollo, sono raffigurate le tre Grazie e sotto le Muse nell’ordine planetario sopraccitato.

ASCESA PER MEZZO DI VOCALIZZAZIONI E MUSICA

Un Dio o uomo divino”, chiamato Thot in Egitto, “distinse le vocali” scrive Platone nel Filebo.

In greco, come in sanscrito, le vocali sono sette; in latino e in italiano cinque, salgono tuttavia a sette se le vocali “o” ed “e” vengono conteggiate ciscuna per due volte, una per il suono aperto e l’altra per il suono chiuso. Gli Egizi avevano un Canto delle sette vocali.

Giacché le sette vocali erano usate al posto dei sette toni della lira a sette corde (accordata sul tetracordo congiunto della scala dorica), secondo i pitagorici si possono leggere le lettere come note. Secondo la dottrina pitagorica, infatti, ogni tono della scala rappresentava la nota di uno dei sette pianeti.Ciascuna vocale pertanto rappresenta una sorta di simbolo magico della musica delle sfere. L’indicazione per determinare il diapason di ciascuno dei toni simboleggiati da una vocale fu trovata nell’Armonia di Nicomaco di Gerasa, che dai pitagorici riprendeva appunto la concezione armonica del mondo. Scrive infatti nel suo Manuale di Armonica: “I suoni di ciascuna delle sette sfere producono un certo rumore, in cui la prima sfera produce il primo suono, e a tali suoni si è dato il nome di vocali.”

Precisa ancora:

Tutti coloro che hanno impiegato la sinfonia a sette suoni in quanto naturale, la prendevano in prestito a questa fonte: non alle sfere ma ai suoni accordati nell’universo, gli unici suoni che noi chiamiamo, fra le lettere, suoni-vocali e suoni musicali. Ma poiché l’analisi di questi punti è di una semplicità elementare, che non può bastare a spiegare questioni complesse, occorre comprendere la concezione dell’Universo dall’affinità, analoga a quella delle corde, e mediante l’accomodamento di una cosa a un’altra

Giovanni Lido assimilava i sette astri alle sette specie di ottava ed alle sette vocali dell’alfabeto greco.

La concordanza di vocali, pianeti, toni, fu fatta propria anche dagli gnostici. Secondo Ireneo, lo gnostico Marco “Il Mago” scrisse: “Il primo Cielo suona la A, il seguente la E, il terzo la E lunga, il quarto nel mezzo grida forte la Potenza (dynamis) della I, il quinto la O, il sesto la U, il settimo e quarto a partire dal mezzo evoca l’elemento dell’Omega”.

Ecco il sistema di Marco, per come riproposto dal Lindsay:

A Luna Nete Re diesis E Venere Paranete Do diesis H / È Mercurio Paramese Si bemolle I Sole Mese La O Marte Lichanos Sol U Giove Parhypate Fa Ω / Ò Saturno Hypate Mi Ipotizzando un’invocazione agli dei planetari cantata sulle sette vocali nei templi dell’antico Egitto, prima di Lindsay, Edmond Bailly scrisse che: ciascuna delle sette vocali greche corrispondeva a uno dei sette corpi del sistema planetario degli Antichi, esprimendo nel contempo una delle sette note della lira di Ermete. Lo schema è un triplice settenario di astri, note e vocali, nel quale si conserva: “alle vocali il loro vocalismo radicale, senza tener conto delle modifiche d’accento causate da tempi e luoghi”:

A Luna Re E Venere Do H / È Mercurio Si I Sole La O Marte Sol U Giove Fa Ω / Ò Saturno Mi Correttamente Boella e Galli osservano che “il sistema descritto discensionale coincide alla scala cosmica e planetaria, non però nella scala musicale ascensionale, di cui al frontespizio della Practica musice di Gaffurius del 1496 (vedasi nelle immagini).

Non ne traggono però le conseguenze, ovvero non imputano l’inversione a errore.

Esaminiamo i due schemi ripartiti in vocali, astri, corde e note. Crediamo che sia il Bailly (che pur era musicologo) che il Lindsay abbiano fatto confusione e qualche errore. Riportando lo schema di Marco, citato da Ireneo, hanno correttamente riportato la sequenza vocalica ascensionale (da Luna a Saturno), ma hanno errato nell’associare a essa la sequenza delle corde e delle note che, invece, ha indicato come discensionale. Inoltre hanno errato nell’associare i rapporti agli astri.

Tornando alle corde, si nota che quelle prima citate nello schema erano le più alte. I nomi greci delle corde delle lire a sette e a otto corde, vedevano la prima nota come più alta e più vicina al suonatore. Le corde erano le seguenti: Nete, Paranete, Paramese; Mese, Lichanos, Parhypate, Hypate (questo lo schema proposto dal Lindsay); oppure Nete, Paranete, Trite, Paramese; Mese, Lichanos, Parhypate, Hypate – le ultime quattro da Mese a Hypate essendo il dito tetracordo, le altre toccate col plettro.

Diverso ancora lo schema ascensionale delle corde del musicista pitagorico Gaffurius, esposto nelle illustrazioni, ove, del precedente schema, sono riportate solo le corde Lichanos, Parhypate, Hypate corrispondenti agli astri Sole, Venere e Mercurio, in senso (ascensionale) ovvero contrario a quello seguito dal Lindsay (che risulta discensionale).

Se si segue la sequenza corretta, ove Nete è la nota più alta e le altre via via più basse, ne risulta che l’ordine è invertito. Ovvero l’ordine corretto dovrebbe essere

A Luna Hypate E Venere Parhypate H / È Mercurio Lichanos I Sole Mese O Marte Paramese U Giove Paranete Ω / Ò Saturno Nete Corrispondentemente anche le note musicali indicate da Bailly e Lindsay dovrebbero essere invertite. Problema: vediamo delle incongruenze e degli errori. Per citarne uno, la nota di Saturno sarebbe un MI che non è ottava del RE diesis (e comunque l’ottava dovrebbe essere nelle stelle fisse!).

Serve fare una breve digressione al fine di capire le sequenze corrette di pianeti, corde e note, ovvero l’armonia stellare. Cominciamo da un ricordo “pitagorico” di Plinio.

Plinio tratta il tema dell’armonia delle sfere inserito nella più vasta trattazione della questione delle distanze astrali.

Molti hanno anche cercato di tracciare gli intervalli delle stelle dalla terra, e hanno dimostrato che il sole dista dalla luna diciannove parti quanto la luna stessa dalla terra. Ma Pitagora, uomo dalla mente sagace, sagace, dedusse che dalla Terra alla Luna c’erano 126.000 stadi, dalla Luna al Sole il doppio da essa, e quindi triplicati fino ai dodici segni (zodiaco), della stessa opinione era anche Sulpicius Gallus.

Ma Pitagora a volte fa appello alla musica anche per la distanza della Luna dalla Terra, dalla Luna a Mercurio mezzo spazio, come da Mercurio a Venere, da Venere al Sole sei volte, dal Sole a Marte un tono [cioè quanto dalla Terra alla Luna], da Marte a Giove un semitono come anche da Giove a Saturno, e quindi sei volte fino allo zodiaco; Così si fanno i sette toni che chiamano διὰ πασῶν ἁρμονίαν Διὸς, questo è il concerto dell’universo. In esso Saturno era mosso al modo dorico, Giove al tono frigio, e così di seguito tutti gli altri, con una sottigliezza piacevole piuttosto che necessaria.

Sentiamo il Pizzani: “All’affermazione che Pitagora avrebbe fissato in 126.000 stadi la distanza dalla terra alla luna —cifra che duplicata e triplicata ci fornirebbe, secondo un’opinione condivisa anche da Sulpicio Galo, l’esatta determinazione delle distanze intercorrenti fra la Luna e il Sole e fra il Sole e la sfera delle Stelle fisse— fa seguito una vera e propria serie di note, pure attribuita a Pitagora, nella quale le distanze fra le otto sfere celesti della tradizione antica (Terra compresa) vengono tradotte in altrettanti intervalli musicali.

La somma di tali intervalli, ammontante a sette toni, corrisponderebbe, secondo Plinio, a quella che gli antichi denominavano diapason harmonia, o intervallo di ottava (che, in realtà, di toni ne comprendeva solamente sei!).”

Il Tannery aveva osservato che questa è la testimonianza più antica della leggenda secondo la quale Pitagora avrebbe previsto la distanza fra la Terra e la Luna e avrebbe, nel contempo, tradotto le distanze astrali in intervalli musicali.

Per quello che importa ai fini di questo saggio, la scala di Plinio sopraccitata risulta quasi identica in Censorino e in Marziano Capella. Questi due autori fissano entrambi in 126.000 stadi la distanza della Luna dalla Terra.

Solo Plinio e Marziano Capella affermano che il suono emesso da ogni corpo celeste corrisponde a un modo (corda) definito.

Mentre Censorino e Marziano Capella identificano tout court la cifra di 126.000 stadi con il primo tono della gamma pitagorica, Plinio non è d’accordo. Egli s’esprime nel senso che il filosofo di Samo avrebbe proposto due criteri del tutto differenti per definire le distanze fra gli astri, senza confonderli o assimilarli l’uno all’altro. Tale distinzione risulterebbe confermata dalla successiva affermazione di Plinio che, secondo un’opinione condivisa anche da Sulpicio Galo, raddoppiando e triplicando la cifra iniziale si otterrebbero, rispettivamente, la distanza fra la Luna e il Sole e fra il Sole e la sfera delle Stelle fisse. La scala pitagorica assumeva, al contrario, che la distanza fra la Luna e il Sole corrisponde a due volte e mezzo (come visibile questa scala non è quella platonica ove il Sole è subito dopo la Luna) e quella fra il Sole e le Stelle fisse a tre volte e mezzo la distanza fra la Terra e la Luna.

Pizzani ne ricava l’ipotesi che

“Plinio avrebbe attinto i suoi dati a due fonti distinte. Varrone gli avrebbe fornito lo schema musicale dell’armonia astrale e la cifra di 126.000 stadi con l’esplicita attribuzione di queste dottrine a Pitagora; da un’opera di Sulpicio Galo, invece, opera esplicitamente menzionata dallo stesso Plinio poco più addietro, deriverebbero le ulteriori indicazioni circa il modo per calcolare le distanze del sole e delle stelle fisse.”

Tornando alle similitudini tra le scale di Plinio, Censorino e Marziano Capella, l’unica consistente differenza fra Plinio e Marziano riguarda un particolare della gamma astrale. Mentre in Plinio si legge che fra il Sole e Marte intercorrerebbe un tono, con l’ulteriore precisazione id est quantum ad lunam a terra, Marziano riduce tale intervallo a un semitono, per come vedremo nel paragrafo relativo.

Vale la pena notare che anche per Igino, la distanza Marte-Sole è assimilata a un semitono.

Su questo punto ancora il Pizzani dice: “Per converso penso esistano fondate ragioni per ritenere che in questo punto il testo di Marziano sia corrotto. Un amanuense, indotto in errore da questa falsa impressione, potrebbe aver creduto di migliorare il testo sostituendo hemitonio sublevatam all’esatta lezione tono sublevatam. Restituendo quest’ultima lezione nel testo di Marziano lo schema ivi descritto verrebbe a coincidere in tutto e per tutto con quello di Plinio e la dipendenza di Marziano dalla Naturalis Historia di Plinio ne verrebbe ulteriormente confermata.”

Dunque, le scale di Plinio e Marziano sono uguali.

Torniamo alla gamma pliniana. S’è detto che essa è quasi identica a quella di Censorino.

L’unica differenza riguarda l’intervallo fra Saturno e le Stelle fisse valutato da Censorino in un semitono e da Plinio in un tono e mezzo.

Pizzani dice

Il fatto però che la serie di Censorino, non meno, del resto, di quella, pur così singolare, descritta da Igino— comprende esattamente sei toni, realizza cioè la diapason harmonia, parrebbe assicurargli una maggiore attendibilità rispetto a quella pliniana comprendente, come s’è detto, ben sette toni. (…)

Occorre osservare che tutte le serie qui menzionate attribuiscono alla terra un suono definito, quasi si trattasse di un corpo celeste qualsiasi. Se è vero che per Filolao la Terra ruotava assieme all’antiterra attorno al fuoco centrale, ma né nei testi più antichi né in quelli successivi, in cui s’accenna all’armonia delle sfere, la Terra viene mai computata. Come abbiamo visto, in origine la gamma astrale prevalente comprendeva solo i sette astri (comprendenti, come sappiamo, la Luna e il Sole) ai quali solo successivamente fu aggiunta la sfera armonica delle stelle fisse.